Discovery

Taung 1 (Taung Child)

Although not the earliest species, A. africanus is still the yardstick by which the other australopithecines are measured and the Taung Child, the first to be discovered, is the holotype of the species. The remains were identified by Raymond Dart in 1924 and consisted of a full face along with the mandible, and a partial endocranial cast, reproducing in limestone the shape and contours of the brain. Not all of its teeth had erupted so it was obviously quite young. Dart initially thought it was probably about six years old but later estimates have revised that downwards to three or four.

Although not the earliest species, A. africanus is still the yardstick by which the other australopithecines are measured and the Taung Child, the first to be discovered, is the holotype of the species. The remains were identified by Raymond Dart in 1924 and consisted of a full face along with the mandible, and a partial endocranial cast, reproducing in limestone the shape and contours of the brain. Not all of its teeth had erupted so it was obviously quite young. Dart initially thought it was probably about six years old but later estimates have revised that downwards to three or four.

Dart argued that the dentition, particularly the reduced size of the canines, which can be quite large among some of the apes, was morehumanlike. Another change he noticed was that the _-_Fig-231.png) location of the foramen magnum, the aperture at the base of the skull where the spinal cord connects to the brain, had moved from the back to a more centrally located position and now faced downwards. This meant that the head was more evenly balanced at the top of the spinal column indicating a habitually upright posture and absolutely necessary for a bipedal animal. It was widely assumed at the time that a large brain was an essential characteristic of all humans and a necessary prerequisite for bipedalism, but the Taung child shows that the reverse was the case. Its brain was estimated to have been no larger than 410 cc, or about the same size as that of a chimpanzee.

location of the foramen magnum, the aperture at the base of the skull where the spinal cord connects to the brain, had moved from the back to a more centrally located position and now faced downwards. This meant that the head was more evenly balanced at the top of the spinal column indicating a habitually upright posture and absolutely necessary for a bipedal animal. It was widely assumed at the time that a large brain was an essential characteristic of all humans and a necessary prerequisite for bipedalism, but the Taung child shows that the reverse was the case. Its brain was estimated to have been no larger than 410 cc, or about the same size as that of a chimpanzee.

The fossil was estimated, on the basis of the extinct animals found in association with it, to have been roughly 2.3 million years old but newer methods applied to later discoveries suggest a date range of 3.67 to 2 million BP for the species.

Sterkfontein

Since 1924 hundreds of hominin fossils have come to light, most of them from an area to the northwest of Johannesburg known as the Cradle of Humankind (see Box 1, right). One of the most productive locations is a cave system at place known as Sterkfontein which was first explored by a team led by Robert Broom in the late 1930s. His investigations were put on hold during World War II but resumed in the late 1940s and continue today.

StS 5 (‘Mrs Ples’) was one of the more complete skulls to be discovered when it was blasted out of the rock in 1947. Broom’s use of dynamite meant that the  skull had been blown to bits and had to be reassembled. Initially, he distinguished it from the Taung skull on the basis of its facial structure and named it Plesianthropus transvaalensis (hence the nickname) but it has since been reclassified as A. africanus. Although initially identified as a female, the age and sex of the specimen has not been conclusively determined and many believe the skull is that of an adult male. Its brain capacity was about 485 cc. Using a combination of uranium-lead dating and palaeomagnetism, the deposits where the fossil was found have been dated to about 2 million years ago. Later in 1947 Broom discovered a partial cranium (StS 71) that was about half a million years older and other skull fragments have turned up since—including a mandible that, based on dental wear patterns, was a match. Taken together, they provide a good indication of the main features of the skull of A. africanus.

skull had been blown to bits and had to be reassembled. Initially, he distinguished it from the Taung skull on the basis of its facial structure and named it Plesianthropus transvaalensis (hence the nickname) but it has since been reclassified as A. africanus. Although initially identified as a female, the age and sex of the specimen has not been conclusively determined and many believe the skull is that of an adult male. Its brain capacity was about 485 cc. Using a combination of uranium-lead dating and palaeomagnetism, the deposits where the fossil was found have been dated to about 2 million years ago. Later in 1947 Broom discovered a partial cranium (StS 71) that was about half a million years older and other skull fragments have turned up since—including a mandible that, based on dental wear patterns, was a match. Taken together, they provide a good indication of the main features of the skull of A. africanus.

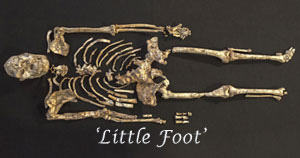

Next to nothing was known about the rest of the body until Broom and John Robinson found an almost complete pelvis along with several connected vertebrae and the upper part of a femur (StS 14) at Sterkfontein. More material has come to the fore since then but it largely consisted of disconnected fragments. The most complete specimen, StW 573 (aka. “Little Foot”) is, unfortunately, of disputed lineage and many would argue that it belongs to a different species (see below).

Morphology

The Skull

StW 505, discovered in 1989 at Sterkfontein (Member 4) is the most complete and the largest cranium found so far. Although in .jpg) rather poor condition, its facial features were distinctive enoughto indicate thatit was probably A. africanus— although there issome disagreement. Most of the face has survived along with a good deal of the base of the skull (the left endocranium and parts of the cranial fossae). Its overall size and the robustness of its facial features may be the result of sexual dimorphism.

rather poor condition, its facial features were distinctive enoughto indicate thatit was probably A. africanus— although there issome disagreement. Most of the face has survived along with a good deal of the base of the skull (the left endocranium and parts of the cranial fossae). Its overall size and the robustness of its facial features may be the result of sexual dimorphism.

In general, the face is rather ape-like in appearance. It has been described as ‘dished’, with flaring cheeks and a somewhat sunken nose, and shows pronounced alveolar prognathism, which means that the lower part jutted out. The cranial vault is low and the forehead recedes noticeably but it is slightly arched (rather than flat) and the boney ridge above the eye sockets, the supraorbital torus, is much smaller is than typical of apes. As noted above, the foremen magnum is located further foreword than is the case with apes and it, along with the occipital condyles that articulate with the vertebral column, faces downwards.

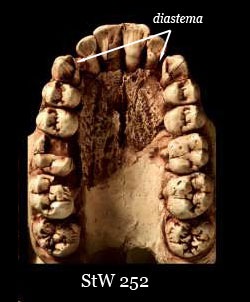

The brain size of the Taung child was on the small side compared with later samples which range from ca. 420-510 cc for adults—about a third the size of modern humans. His skull is more jaws than brain and the main distinguishing features are found in its dentition. Like us, A. africanus had a full set of 32 teeth. They were equipped with much smaller, less fang-like canines than apes so there were much smaller gaps (diastema) between the upper canines and incisors to accommodate the lower ones. On the other hand, its cheek teeth (the premolars and molars) were larger, very thickly enamelled, and heavily worn— evidence that their diet required long, hard chewing. They had four low, rounded cusps and low crowns used for crushing and sharp edges designed for shearing fibrous material. These activities meant adjustments to the facial musculature. The cheekbones shifted forward so that the attached jaw muscles could exert more downward pressure. The structure of their inner ear which affects balance as well as hearing is also becoming more humanlike.

The Body

The same mixture of the ape and human applies to the rest of their skeletons as well, with features adapted both to an arboreal and terrestrial lifestyle. The pelvis is very human-like. The ilia of StS 14 are shorter and broader than those of any ape and, although only the upper part survives, the sacrum  was wide and appears to tilt forward as it does with humans. There is some evidence of lumbar lordosis (an outward curving of the lower vertebrae)— another human feature associated with an upright posture. On the other hand, the atlas bone at the top of the vertebral column is more ape-like, well-adapted for swivelling the head up and down as well as from side to side— very helpful for climbing and clambering among the branches

was wide and appears to tilt forward as it does with humans. There is some evidence of lumbar lordosis (an outward curving of the lower vertebrae)— another human feature associated with an upright posture. On the other hand, the atlas bone at the top of the vertebral column is more ape-like, well-adapted for swivelling the head up and down as well as from side to side— very helpful for climbing and clambering among the branches

The hind legs are a similar mixture. Two distal femora, also from Sterkfontein, had bicondylar angles much greater than those found in apes indicating that A. africanus had a ‘valgus’ knee appropriate for bipedal locomotion. In another fossil (StW 573) the angle where the tibia meets the foot is less suited to climbing than it is to walking. Nothing has been found so far to suggest an ‘adducted hallux’ (a big toe that is aligned with the others rather than one that is prehensile). However, there is some debate over the exact classification of StW 573 and its place in the chronological scheme of things. One of its feet has no toes (phalanges) and the other is missing entirely. Like apes, the arms are longer than the legs. Their fingers were long and curved and, with opposable thumbs, were capable of a powerful grip. Their shoulders and back (epaxial) muscles were adapted mainly for suspension and climbing. The question that remains is: were these necessary for their current lifestyle or were they simply holdovers from a previous mode of existence, soon to disappear as circumstances changed.

All hominins exhibit some degree of sexual dimorphism—males are taller and heavier than females to one degree or another. It has been suggested that the males stood about 140 cm tall and weighed about 40 kg, while the females were about 125 cm in height and weighed about 30 kg. However, the sample size is small and mostly made up of incomplete specimens.

Environment

During the Late Pliocene, the south African landscape was characterized by shrinking areas of rainforest separated by expanding grasslands known as savannahs, a process that had begun in the Late Miocene. These were colonized by heat tolerant, drought resistant C4 grasses but included areas of woodland along with isolated stands of trees or individual trees  and thickets of rather prickly shrubs such as acacia, much like the environment of some of the protected areas of South Africa today (far right). Faunal assemblages preserved as fossils Sterkfontein and other cave sites include animals from a variety of habitats including bush savannah, open woodland and grassland. Prominent among them are the remains of large herbivores, including both grazers (grass eaters) and browsers (leaf eaters). Many of the species are now extinct but there are quite a few whose descendants can still be found in the area. Most of them evolved during the Miocene to take advantage of the new conditions. It was then that specialized feeders such as bovids first appeared. Their digestive system was essentially one big fermentation tank that enabled them to extract enough nourishment from the vast amounts of grasses they had to consume. The bovids included giant buffalo weighing as much as a ton (1,000 kg) and various wildebeest (including a giant version weighing half a ton). As in more recent times, there were also a large number of equids such as zebra and an extinct three-toed horse called a Hipparion roaming the plains, along with all kinds of antelope some of whom grazed while others browsed. There wererhinoceros and hippo as well as ancient species of giraffe.

and thickets of rather prickly shrubs such as acacia, much like the environment of some of the protected areas of South Africa today (far right). Faunal assemblages preserved as fossils Sterkfontein and other cave sites include animals from a variety of habitats including bush savannah, open woodland and grassland. Prominent among them are the remains of large herbivores, including both grazers (grass eaters) and browsers (leaf eaters). Many of the species are now extinct but there are quite a few whose descendants can still be found in the area. Most of them evolved during the Miocene to take advantage of the new conditions. It was then that specialized feeders such as bovids first appeared. Their digestive system was essentially one big fermentation tank that enabled them to extract enough nourishment from the vast amounts of grasses they had to consume. The bovids included giant buffalo weighing as much as a ton (1,000 kg) and various wildebeest (including a giant version weighing half a ton). As in more recent times, there were also a large number of equids such as zebra and an extinct three-toed horse called a Hipparion roaming the plains, along with all kinds of antelope some of whom grazed while others browsed. There wererhinoceros and hippo as well as ancient species of giraffe.

Naturally these attracted the attention of predators and scavengers who fed on the scraps of the kill,and amongthe fossils found in the cave deposits werethose of a number of large carnivores including a various species of felids such sabre-toothed cats, lions .png) and leopards. There were also hyenas, including a number of extinct species; and canids such as jackals and wild dog. Marks around the eyes of the Taung Child suggest that it was killed by an eagle, a conclusion supported by the presence of egg shells in the same deposit.

and leopards. There were also hyenas, including a number of extinct species; and canids such as jackals and wild dog. Marks around the eyes of the Taung Child suggest that it was killed by an eagle, a conclusion supported by the presence of egg shells in the same deposit.

Dart felt that the changes in skeletal morphology of A. africanus represented the adaptations needed for apes to move out from the forests, where their primate ancestors had evolved and thrived for 50 million years, and onto the harsher environment of the open plains. Their upright posture would have enabled them to see much farther to the horizon and left their handsfree to carry weapons and whatever food they had managed to accumulate. It also made them far more able to manage infants and toddlers

Unlike the apes who confined their activities to the forest and lived mainly on a diet of leaves and fruit, A. africanus, combining rudimentary bipedalism and climbing skills, was able to take advantage of the resources of all of the different biospheres that emerged in the Pliocene and moved among them according to seasonal availability of resources. The competition was fierce, however, and it would seem that A. africanus was a victim much of the time. Sleeping on the ground would have been very dangerous indeed, and it is more likely that they made nests in the trees where they spent the night. Many of the hominin bones that were found in the caves may have been dragged in by predators (probably leopards who are known to cache their prey), or scavengers such as hyenas or jackals.

Diet

Microwear analysis of the teeth and carbon isotope analysis of the bones indicate that C4 grasses and rhizomes along with roots, tubers and fruit made up much of their diet, either by consuming themdirectly or by eating the flesh of other animals that did.  Crunching harder items such as seeds and nuts is also indicated but this seems to have been rather infrequent, perhaps only in direst need. This would have caused increased wear and no doubt accounts for the thickening of the enamel on their molars. A recent study has found evidence of acid erosion on the teeth of A. africanus, probably caused by consumption of fruit. Animal protein likely came as a result of scavenging but they were probably also capable of killing small, more defenceless animals—the young, the old and the infirm. Birds eggs were undoubtedly on the menu as were insects such as termites and insect larvae. Some sort of tools would have come in handy when it came to breaking into a termite mound—or digging up tubers for that matter—but there is no solid evidence for their presence.

Crunching harder items such as seeds and nuts is also indicated but this seems to have been rather infrequent, perhaps only in direst need. This would have caused increased wear and no doubt accounts for the thickening of the enamel on their molars. A recent study has found evidence of acid erosion on the teeth of A. africanus, probably caused by consumption of fruit. Animal protein likely came as a result of scavenging but they were probably also capable of killing small, more defenceless animals—the young, the old and the infirm. Birds eggs were undoubtedly on the menu as were insects such as termites and insect larvae. Some sort of tools would have come in handy when it came to breaking into a termite mound—or digging up tubers for that matter—but there is no solid evidence for their presence.

Society

There is simply not enough evidence to come to anything more than the most general conclusions about group dynamics. It has been suggested on the basis of strontium isotope study of their teeth that groups were patrilocal, that the females came from elsewhere. Males apparently stayed in the areas where they were born but it is uncertain whether or not they were expelled from the group as happens among gorillas where there is one dominant male and a harem of females with their offspring. Among chimpanzees, on the other hand, while there may be one dominant males, the losers stay within the group as long as they know their places. If a group has to survive out in the open with all its inherent dangers it is good ‘policy’ to have a gang of sturdy henchmen. The relatively small canines of A. africanus would seem to indicate that the level o male-male aggression was lower than in other species.

Suggested Reading

| Ayala, F. J. and C. J. Cela-Conde | (2017) | Processes in Human Evolution. Second Edition |

| Barham, L. & P. Mitchell | (2008) | The First Africans. African Archaeology from the Earliest Toolmakers to Most Recent Foragers |

| Broom, R. | (1938) | The Pleistocene Anthropoid Apes of South Africa. Nature |

| Cartmill, M. & F.H. Smith | (2022) | The Human Lineage. Second Edition |

| Dart, Raymond | (1925) | Australopithecus africanus: The Man-Ape of South Africa. Nature |

| Lewen, Roger | (2015) | Human Evolution. 5th Edition. |

| Owen-Smith, N. | (2021) | Only in Africa |

| Scarre, C. (edit.) | (2018) | The Human Past. Fourth Edition |