I. The Cretaceous and Palaeogene Periods

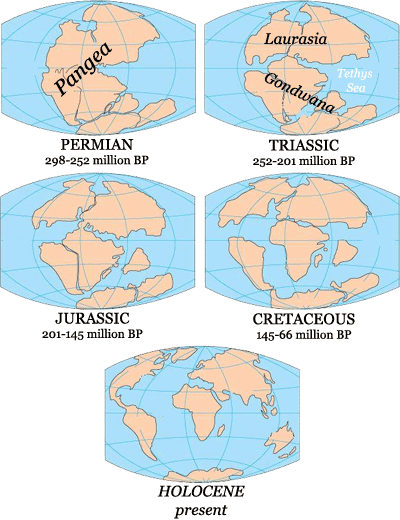

The geological history of Earth has been characterized by the assembly and break up of large land masses known as supercontinents through the process of plate tectonics. The latest such supercontinent is known as Pangaea which finally came together during the Permian epoch (c. 299-252 million BP) and included almost all of the earth’s landmasses. However, it was not long until it began to break up again. The northern part known as Laurasia which consisted of much of what is now Eurasia and North America began to separate during the Triassic Period (c.252-201 million BP). The southern part was known as Gondwana and was made up of what were to become Africa, South America, Antarctica, Australia and India. It began to break up during Jurassic Period (c. 201-145 million BP).

Cretaceous Period (c. 145 to 66 million BP)

Gondwana finally split apart some 100 million years ago, during the Cretaceous, and the various continents moved ever so slowly to their present positions with India moving towards and eventually colliding with Eurasia. So, for much of this period, Africa and Arabia were separated from Eurasia by what is known as the Tethys Sea. As they moved away, the drifting continents left the central core—Africa—exposed to severe erosion by wind and water which pretty much scoured it, removing almost all of the fossil evidence.

It was at some time around 80 million years ago, that the order Primata emerged somewhere in Asia. These early primates were arboreal creatures spending most of their lives in the treetops, feeding on leaves and fruit, and rarely (if ever) on the forest floor. They had larger brains for their size than other mammals and were very social animals, which helped to ensure their long-term survival. Large brains came at a price, however, particularly when it came stages of growth and development. Reproductive maturity came relatively late making the young ones more vulnerable to predators. By about 74 million BP prosimians such as bush babies and lemurs began to appear in sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar.

The Cretaceous ended with an environmental catastrophe, the result of a collision about 66 million years ago with a large asteroid, one that created an enormous crater just off the north coast of the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. The impact threw up a cloud of dust that blocked out the sun completely, preventing photosynthesis and putting an end to plant growth. This led to what has been called the Cretaceous/Palaeogene Mass Extinction when about 75% of all plant and animal species disappeared from the fossil record at this time—most notably, all of the non-avian dinosaurs. By the end of the Cretaceous (c. 66 million BP) the whole of the interior, apart from the Atlas Mountains in the north and the Cape Fold Mountains in the south, was one vast, gently undulating plain.

Palaeogene Period (c.66-23 million BP)

Palaeocene Epoch (c. 66-56 million BP): Although catastrophic for the dinosaurs, the long term effects of the asteroid strike were negligible as far as the climate was concerned. Once the dust settled, conditions returned to what they had been before. For most of the planet that meant a warm, moist climate—either tropical or subtropical—and, although it was cooler and more temperate towards the poles, there were no icecaps. The average global temperature was somewhere around 25°C, or about 10° warmer than today’s and carbon dioxide levels were also much higher than they are now. During much of this period, the Tethys Sea, allowed sea-water to circulate freely all around the continent, keeping temperatures and precipitation stable.

Unfortunately, due to millions of years of severe erosion that pretty much levelled most of the continent during the latter part of the Palaeogene, any prior fossil remains have been virtually obliterated, making it impossible to say very much about the palaeoecology of the continent. No dinosaur bones have survived nor those of any of the large mammals that succeeded them.

Eocene Epoch (c. 56-33.9 million BP): The Eocene epoch, which followed the Palaeocene and lasted from about 56-34 million BP, began with another enormous environmental disaster, known as the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), which saw the release of massive amounts of carbon dioxide, which rose to about five times today’s levels, into the atmosphere along with other greenhouse gases such as methane. This led to a sudden rise in average global temperature of 5-8°C. It was of enormous benefit to plant kingdom and soon much of the earth was blanketed with tropical or semi-tropical forests.

Aerial view of the Brazilian rainforest

One group of plants thrived particularly well. These were the angiosperms, flowering plants that produced syrupy nectar and/or fruits packed with sugar—primarily to entice insects, birds and other animals to help them reproduce by transporting pollen from one plant to another. Many varieties of birds, insects and reptiles emerged to take advantage of the new abundance and among them were the first primates who originated in Asia but first appeared in Africa about 55 million years ago. By the end of the epoch, they had given rise to the Catarrhini, the earliest monkeys found throughout the Old World. Their sister branch, the Platyrrhini had by then moved to what is now South America.

Oligocene Epoch (33.9-23 million BP): The Oligocene saw a cooling and drying trend which led to the global spread of broad-leaved, deciduous woodlands at the expense of evergreen tropical and subtropical rainforests. The mammals are often described as ‘Afrotheria’, meaning that, in the absence of a land bridge to Eurasia, they are unique to the continent. The most characteristic thing about them was their size and many of them have been described as ‘megaherbivores’.

Early in the Oligocene, the catarrhini split into two sub-families, Colobinae (colobus monkeys) that subsisted on leaves and fruit along with the more omnivorous Cercopithecidae, out of which the apes emerged.

Fayyüm Fossils

Fossils dating mainly to the Late Eocene/Oligocene have been recovered from a number of locations in the Fayyüm Depression, in the Western Desert of Egypt. The Fayyüm had once been a shallow inland sea surrounded areas of marshland, ponds and tropical forest at the time. It has produced hundreds of fossils belonging to primitive birds, fish, reptiles and mammals have been identified. These include members an archaic sub-order of whales (Archaeoceti) found at Wadi al Hitan (“Valley of the Whales”), which were intermediate between terrestrial and aquatic forms, along with early species of manatee (Sirenia).

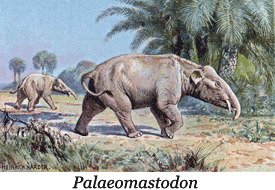

The Jebel Qatrani Formation was on the margin of the depression and had apparently been a marshy region, judging by the remains of the birds found there. These included osprey (Pandionidae), flamingo (Phoenicopteridae) and heron (Ardeidae). Among the fossils found at Jebel Qatrani are a number of large, browsing  ungulates, Arsinoitherium zitteli (a large herbivore that resembled a rhinoceros but was actually more closely related to manatees), various members of the Proboscidea order (extinct species of elephants), as well as an early species of hyrax (Hyracoidea) which came in a variety of shapes and sizes, some as big as a large antelope. The proboscideans were also diverse and included the Moeritherium, a semi-aquatic animal with small tusks and no trunk resembling a tapir in size and shape; and the Palaeomastodon, another marsh dweller that had tusks on both the upper and lower jaw and a small trunk. Conspicuous by their absence were grazing animals. However, there were a number of primates around, but the most important from our human point of view was Aegyptopithecus zeuxis, reckoned by some to be the common ancestor of the apes, but the jury is still out.

ungulates, Arsinoitherium zitteli (a large herbivore that resembled a rhinoceros but was actually more closely related to manatees), various members of the Proboscidea order (extinct species of elephants), as well as an early species of hyrax (Hyracoidea) which came in a variety of shapes and sizes, some as big as a large antelope. The proboscideans were also diverse and included the Moeritherium, a semi-aquatic animal with small tusks and no trunk resembling a tapir in size and shape; and the Palaeomastodon, another marsh dweller that had tusks on both the upper and lower jaw and a small trunk. Conspicuous by their absence were grazing animals. However, there were a number of primates around, but the most important from our human point of view was Aegyptopithecus zeuxis, reckoned by some to be the common ancestor of the apes, but the jury is still out.

Further Reading

| Barham, L. & P. Mitchell | (2008) | The First Africans. African Archaeology from the Earliest Toolmakers to Most Recent Foragers |

| Clark, J. Grahame | (1969) | World Prehistory: A New Outline |

| Lewen, Roger | (2005) | Human Evolution. 5th Edition. |

| Maslin, Mark | (2017) | Cradle of Humanity |

| Maslin, Mark, et. al. | (2014) | East African climate pulses and early human evolution. Quaternary Science Review. |

| Owen-Smith, Norman | (2021) | Only in Africa. The Ecology of Human Evolution |

| Shea, John J. | (2017) | Stone Tools in Human Evolution |

.jpg)