Archaeologically, the Middle Palaeolithic in North Africa, Western Asia and Europe is marked by the appearance of a new chipped stone industry known as the Mousterian, after the site of Le Moustier in the Dordogne region of Southwest France where it was first identified in the 19th century. Since then, the area has been thoroughly combed by archaeologists and most of the analysis has been done on the lithic assemblages they recovered.

Lithic Technology

There is a sequence of stages in the production of a stone tool (lithos= Greek, ‘stone’). First one must acquire a nodule of suitable stone, one that is both hard enough to keep an edge and brittle enough to fracture easily. Fine-grained crystalline rocks, such as chert, flint, obsidian or quartzite are preferred. The care that went into its selection depended on the quality needed for the particular tool required, Most tools were of the single-use variety, a flake with a sharp edge that could be discarded after use. They were simple tools and could be made out of whatever material lay to hand. Others were more carefully worked and were kept until they wore out. These would have been made out of more fine-grained flint with fewer impurities and would have produced a more predictable flake. Often the source of this material was at some distance and some sacrifice had to be made to obtain it.

Making simple flake tools could be a fairly simple andstraightforward process. You simply bashed one nodule of suitable rock against another and then rummaged through the flakes to find one that was the preferred size and shape with a good, sharp edge. You might then knock some flakes from the opposite edge so that it fit comfortably in the hand when you used it. This secondary flaking is known as ‘retouch’. The majority of artefacts found on Mousterian sites in SW France, 70% on average, were made out of material obtained within a walking distance of an hour or so (<5 km) and the bulk of the rest of it could be picked up in the course of one’s daily round. All stages of lithic reduction are represented in this material, indicating that most of the manufacturing process was done in situ.

|

Lithic Core from the Negev |

However, at most sites there was also a very small component of the assemblage (1-2%), mainly consisting of finished tools or highly reduced flake blanks, made from high quality flint from sources as far away as 100 km and sometimes much further. The processes involved in working this material were much more complex. First, the outer cortex had to be trimmed away, something that was most often done at the source. Then work began on shaping the core and creating striking platforms so that ‘preforms’ of predetermined size and shape could be struck using a hard stone hammer. This sort of technology is known as the ‘prepared core technique’ and appears to have developed independently in a number of locations during the latter part of the Lower Palaeolithic. The flakes were often then retouched by detaching smaller, thinner flakes using a ‘soft’ hammer (below right) made out of wood, bone or antler. These gave the knapper much more control over the final shape of the object. Retouching was used to shape the final form of the tool so that it fits more comfortably in the hand, for example. It was  also commonly used to resharpen damaged or blunted edges. In many cases this was repeated until little was left of the original shape.

also commonly used to resharpen damaged or blunted edges. In many cases this was repeated until little was left of the original shape.

Exactly how the material was obtained is unknown. It is possible that one or more members of the group were dispatched to the source to collect it but this seems unlikely, given the time and effort. It is more likely that it was acquired at some point during the seasonal or annual movements of the entire group in pursuit of game or to gather fruits and vegetables as they became available. Another intriguing possibility is that some sort of exchange mechanism was worked out with one or more neighbouring groups. Periodic gatherings were a necessity among such dispersed populations for a variety of reasons—social and biological as well as economic. They could exchange information, resolve disputes and exchange marriage partners among other commodities.

It is suspected that many of these sites, particularly the ones located at or very near flint sources, were specialist ‘factory’ sites but this, like so much else about the Middle Palaeolithic, is almost impossible to prove. Such things as the absence of faunal remains or well-used hearths would suggest at least the possibility of such sites. As would the presence of numerous reduction flakes and cortex fragments with a dearth of finished tools. As far as extraction is concerned, it is highly unlikely that any actual mining was involved. In the Perigord flint nodules are embedded in limestone formations and would have been very difficult to extract without proper picks. They were more likely have been the products of erosion and collected from the scree at the base of a slope or from river gravels.

Levallois techniques

A characteristic of the Middle Palaeolithic is the variety and flexibility of core reduction techniques, seemingly designed to produce different types of flake for the manufacture of specific tools. At least half a dozen different techniques have been identified within the Levallois tradition, the hallmark of Middle Palaeolithic flint working and there are a number that fall outside it. The variable quality of the raw material was undoubtedly a factor too.

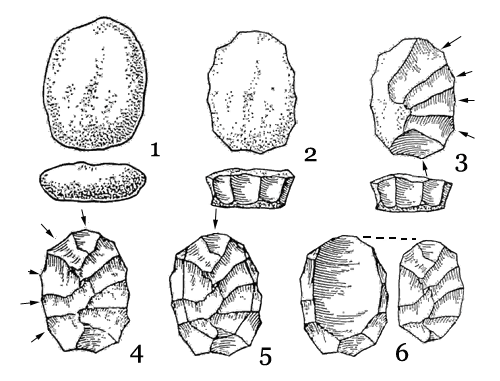

The Levallois technique gets its name from the Parisian suburb, Levallois-Perret, where it was first identified in the 19th century. It represents a significant technological advance over previous methods of lithic reduction. The techniques employed can be quite complex, involving five or six stages of preparation just to strike off the blank, which then usually required yet more work before the finished product emerged. Typically, broad flakes were knocked off a roughly oblong core to produce a domed blank that resembled a tortoise shell. Then, a number of striking platforms were prepared using a soft hammer to strike vertical blows around the upper surface of the core. In the so-called ‘classic’ technique the flaking went all around the perimeter so that one or more oval or rectangular flakes, ideal for scrapers or knives, were detached. Points were produced by preparing one or both ends of the core in such a way that triangular flakes were produced. After the first flake was detached, the core was then reshaped so that a second could be struck and the process repeated until the core was exhausted.

Stages in the production of a ‘classic’ Levallois core (from Paul Mellars, 1996)

The Levallois technique far from the only method used to produce flint tools. Another was the Quina-Mousterian which saw the production of flakes suitable for scrapers from an elongated oblong nodule. A similar nodule might have one end struck off which was then used as a platform for detaching blades from along the length of the core. They might also be prepared so that a succession of flakes could be struck with very little reshaping. This was a much more economical use of raw material—important if it had to be transported some distance. Generally this was done on an oblong core with flakes being struck from either or both ends (unipolar or bipolar) to produce blades, or working around the circumference which produced more points and potential scrapers. This could be carried on until the core became unworkable and was discarded.

The Mousterian Tool-kit

The classification of Mousterian stone tools is a tricky business since many of the standard types appear to overlap with each other. It is often hard to decide whether a given item is a scraper or a point, for example. Experimental trials using modern reconstructions and applying them to a range of different materials—wood, bone, flesh, skin, etc.—show different patterns of wear when viewed under a microscope. Not only that, but they can indicate how the tool was used—for cutting, slicing, scraping or piercing. The results can then be compared to the patterns visible on prehistoric specimens, a process known as use-wear or microwear analysis.

The bulk of the classification was done by François Bordes in the 1950s and he did a very thorough job to say the least—there are dozens of varieties of scrapers alone. His work has been criticized, by Nicholas Rolland and Harold Dibble among others, because it does not take into account the fact that a particular item may have been altered by repeated sharpening and/or remodeling to create an entirely different form than the original.

Bordes also identified a number of ‘industries’ within the region. An industry is made up of several lithic assemblages with a range of tools that are grouped together on the basis of common manufacturing techniques or the finished shape. On this basis, he was able to define the following:

| 1. | Typical Mousterian | Defined by a high incidence (20-55%) of racloirs compared to other tool types and an absence of features that typify the other industries. | ||

| 2. | Charentian | La Quina: has a low incidence (<10%) of Levallois technique. | ||

| La Ferrassie: has a high incidence (14-30%) of Levallois technique | ||||

| 3. | Le Moustérien de tradition acheuléenne |

|

||

| 4. | Denticulate Mousterian | A low incidence of racloirs (<20%) and, obviously, a high incidence of notched tools and denticulates (40-60%) |

Bordes initially believed these groupings represented ‘tribal’ divisions because they appeared to cluster in different parts of the region. This view was challenged by Louis Binford in the 1960s who felt that they may have also represented different activities carried on at different sites. So, a temporary encampmentused by hunters stalking and butchering animals would have a different assemblage to one where plants were processed or where  woodworking was done. In addition, the stratigraphy of cave sites in the Dordogne and elsewhere in Europe have clearly shown that these industries are also successive to a certain extent.

woodworking was done. In addition, the stratigraphy of cave sites in the Dordogne and elsewhere in Europe have clearly shown that these industries are also successive to a certain extent.

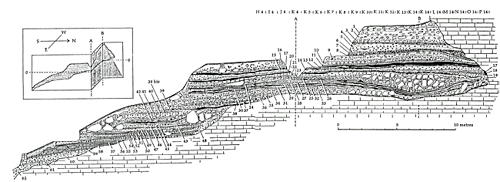

At Combe Grenal (left) over 60 levels of deposit have been uncovered (below). The lowest of these contain Acheulean material but Typical Mousterian material begins to appear in Level 54 and continues intermittently until level 40. This span of time dates to MIS Stages 5a-e (c.120-70,000BP), beginning in the Last Interglacial and continuing until the earlier part of the Last Glacial Period. In level 38 there is an occupation with Denticulate Mousterian tools and somewhat above that, several layers (35-27) belonging to the La Ferrassie tradition—with some admixture of Typical Mousterian elements—followed by a number of others (26-21 and 19-17), belonging to the La Quina. Then there are several layers (96-11) that have Denticulate assemblages. These are all associated with MIS Stage 4 (c. 70-57,000BP) and contain faunal material, mainly reindeer, associated with a cold, tundra-like climate. The latest Middle Palaeolithic levels (4-1) are characterised by material belonging to the Mousterian of Acheulean Tradition when the occupants experienced a somewhat warmer climate—reindeer were replaced on the menu by aurochs, bison and red deer—and probably belongs to MIS3, a brief interstadial that occurred about 50,000 years ago

Combe Grenal Stratigraphy, Bordes 1972. Click the drawing for a larger and clearer version.

It seems certain that the La Quina industry developed from the La Ferrassie, since it is invariably found above the latter at other sites too. So, it seems reasonable to lump the two of them together under the general label of Charentian. It is also clear that the MTA is later than the Charentian and is the last of the Mousterian sequence. Within the MTA it appears that Type A, which is distinguished by the presence of hand axes, is earlier than B. Typical Mousterian and Denticulate sites have a much wider distribution than the others and are often found interspersed with them chronologically. Typical Mousterian is a bit of a ‘grab bag’, characterized more by what it does not contain rather than what it does, where assemblages that do not fit the other profiles are dumped. Most of the sites defined as Typical Mousterian date to the period from last interglacial to the beginning of the last glacial period (the entire MIS5 sequence or ca.120-80,000 BP). The latest have been dated to the middle or late stages of MIS3 and are best represented at Combe Grenal, where they are found stratified within the sequence of other industries. Denticulates are a rather specialized tool, probably associated with trimming wood and most likely represent episodes of specific activity, a job site rather than a base camp.

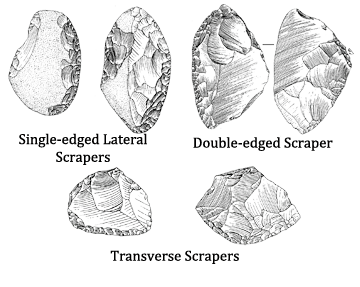

Scrapers (racloirs)

These simple but distinctive tools form a major component of the Mousterian industry. They are characterized by a careful retouching, generally along one of the long sides of the flake, designed to produce a smooth, sharp cutting edge. Use/wear analysis indicates that they were used as cutting or slicing tools and applied to wood or flesh. They were also evidently used to scrape the fat from animal skins and the flesh from bones.

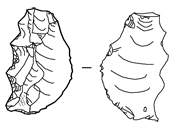

Side Scraper (Racloir) from Grotte de le Placard, Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Three Views.Bordes has divided and subdivided them in a number of different ways—the relationship of the retouched edge to the striking platform of the flake; the form of the retouched edge (straight, convex or concave); whether or not they were worked on the top and/or bottom; etc. Rolland and Dibble argue that the final form of the tool, the one that ended up being discarded had probably been greatly modified and bore little resemblance to the original, which they imagined was an unretouched flake with a sharp edge. There is ample evidence to show that the latter were used and it is easy to imagine, if good quality flint was in short supply, that they may well have been reworked but that does not seem to be the case. There are a number of sites where suitable material is readily available but, nevertheless, the local industry is dominated by typical retouched forms which, by the way, tend to be much more useful; having longer, straighter and smoother edges.

Points

Levallois Point from Grotte de le Placard, Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Three Views

Pointed tools, defined as symmetrical, somewhat elongated triangles, are another distinctive feature of Middle Palaeolithic assemblages. They were almost certainly designed to be hafted to wooden shafts or handles—the bases were often trimmed to facilitate this and show signs of abrasion and polishing—and used as stabbing weapons or even missiles. The tips of many examples had been carefully sharpened and occasionally show signs of impact damage. Bordes felt that some, thicker and less symmetrical than the rest, were actually types of racloir which he classified as déjeté or convergent

Notched Tools and Denticulates

These are rather scrappy looking tools and had been largely ignored until well into the last century when Bordes took a closer look at them. Notched tools a single, fairly large indentation worked along one edge of the flake while denticulates are characterized by a series of smaller, juxtaposed notches.  The notches were produced either by a single, sharp blow or by a succession of lighter, repeated blows. Denticulates may have as few as two to as many as twelve notches and can be further distinguished by the position of the edge in relation to the long axis of the flake and whether there was one worked edge or two. In some cases the two edges converged creating what Bordes dubbed a ‘Tayac’ point.

The notches were produced either by a single, sharp blow or by a succession of lighter, repeated blows. Denticulates may have as few as two to as many as twelve notches and can be further distinguished by the position of the edge in relation to the long axis of the flake and whether there was one worked edge or two. In some cases the two edges converged creating what Bordes dubbed a ‘Tayac’ point.

The function of these tools is subject to much speculation. The notched tools somewhat resemble modern spoke shavers and may have been used in much the same way. Certainly microwear analysis suggests that they were applied to wood and the same appears to be true of most of the denticulates although a few were used to process other plant material or animal flesh. However, the softer the material, the less trace it leaves.

Backed Knives

These are made from an elongated flake with a sharp, regular, unretouched edge running along one of its long sides and an abruptly retouched edge on the other. The former was clearly the working edge while the other may have been blunted to make it fit more comfortably in the hand, although some may have been hafted. They come in a wide range of shapes, from broad, heavy flakes to thin, narrow blades. There is little use-wear data but those that have been studied show signs of use on wood, bone and flesh, so no surprise there. In France, they tend to be found in association with industries belonging to the Mousterian of Acheulean Tradition and often make up a sizable proportion of the assemblage.

These are made from an elongated flake with a sharp, regular, unretouched edge running along one of its long sides and an abruptly retouched edge on the other. The former was clearly the working edge while the other may have been blunted to make it fit more comfortably in the hand, although some may have been hafted. They come in a wide range of shapes, from broad, heavy flakes to thin, narrow blades. There is little use-wear data but those that have been studied show signs of use on wood, bone and flesh, so no surprise there. In France, they tend to be found in association with industries belonging to the Mousterian of Acheulean Tradition and often make up a sizable proportion of the assemblage.

Bifaces (Hand-axes)

.jpg) There are a number of tools that fall into this broad category but the most common is one that had been around for several hundred thousand years—the hand-axe—whichwas characteristic of the Acheulean industry which belonged to the Lower Palaeolithic. These are characterised by careful shaping and retouching on both faces of a flint core and around the entire circumference to produce a symmetrical tool, seemingly designed for digging but perhaps also for display. Normally, one end is pointed to a greater or lesser degree while the other is rounded and broader. The longer and more pointed examples, known as Micoquien (after the site of La Micoque in the Dordogne, date to the last interglacial, shown left) which lasted from about 130-115,000 BP. However, most of the bifaces recovered from the last glacial period are described as ‘cordiform’ (heart-shaped) although not all of them are.

There are a number of tools that fall into this broad category but the most common is one that had been around for several hundred thousand years—the hand-axe—whichwas characteristic of the Acheulean industry which belonged to the Lower Palaeolithic. These are characterised by careful shaping and retouching on both faces of a flint core and around the entire circumference to produce a symmetrical tool, seemingly designed for digging but perhaps also for display. Normally, one end is pointed to a greater or lesser degree while the other is rounded and broader. The longer and more pointed examples, known as Micoquien (after the site of La Micoque in the Dordogne, date to the last interglacial, shown left) which lasted from about 130-115,000 BP. However, most of the bifaces recovered from the last glacial period are described as ‘cordiform’ (heart-shaped) although not all of them are.

They are considered a hallmark of the MTA and are missing within the other traditions in SW France—La Quina, La Ferrassie, etc. Apart from the cordiform varieties there a number that are oval or triangular. They may be made from nodules or large flakes of flint and range from 5-20 centimetres in length, apparently diminishing with time. In addition, a small number of bifacial leaf-shaped points have been found in central and eastern Europe and tools described as cleavers or choppers have been found in northern Spain.

Other Tools

Implements identified as end-scrapers have been found in small quantities at a number of sites but it is unclear whether these were made deliberately or failed attempts at making something else, such as a backed knife. Doubts also apply to the items identified as burins, a tool somewhat resembling a modern utility knife and used for graving. They also represent a very small component in Mousterian assemblages and may well have been produced by accidental breakage. Burins, which are designed to engrave wood or bone, were common in the Upper Palaeolithic and later periods when there was a lot of worked bone and wood around. They are rather scarce in the Middle Palaeolithic, however, and it is thought that much of what is classified as burins are simply damaged blades.

Implements identified as end-scrapers have been found in small quantities at a number of sites but it is unclear whether these were made deliberately or failed attempts at making something else, such as a backed knife. Doubts also apply to the items identified as burins, a tool somewhat resembling a modern utility knife and used for graving. They also represent a very small component in Mousterian assemblages and may well have been produced by accidental breakage. Burins, which are designed to engrave wood or bone, were common in the Upper Palaeolithic and later periods when there was a lot of worked bone and wood around. They are rather scarce in the Middle Palaeolithic, however, and it is thought that much of what is classified as burins are simply damaged blades.

Tool ‘Design’

An important question when it comes to assessing the intellectual capability of Neanderthals, is to what degree they were working from a mental template when crafting the form of a particular tool. Do the tools exhibit what is termed an ‘imposed form’? This is certainly the case during the Upper Palaeolithic when aesthetic considerations count for as much as utility. The exceptions to this general rule are the bifaces, particularly the hand axes, and leaf-shaped points which are relatively standardized in appearance. The reasons for this—functional, technological or cultural—are not yet fully understood.

Another factor to be considered is the quality of the raw material. It seems reasonably clear that some tools such as denticulates, cleavers, choppers etc., were made out of whatever material was locally available, used for the task at hand and then discarded, while others such as racloirs and hand axes were manufactured using more fine-grained flints, often obtained from more distant sources. While notched tools and denticulates are rather simple to make, racloirs and hand axes require more careful treatment so it is a good idea to use the best materials available. It is also in the best interest of the users to extend the life of these tools through reshaping and resharpening.

Sources of Raw Material

The majority of artefacts found on the Mousterian sites in SW France, 70% on average, were made out of material obtained within a walking distance of an hour or so (<5 km) from where they were found. All stages of lithic reduction are represented at the site, indicating that most if not all of the manufacturing process was done there. As mentioned above, the overwhelming majority of the tools produced were fairly simple types and were discarded after a single use. However, there was generally a tiny part of the assemblage (1-2%) that was made out of higher quality flint from sources as far away as 100 km and sometimes even further. It was usually made up of finished tools or flake blanks that could be quickly worked up. Actual cores are conspicuous by their absence. The tools were clearly valued, showing evidence of being reshaped and resharpened to get the maximum use out of them.

By what means the material was obtained is unknown. It is possible that one or more members of the group were dispatched to the source to collect it but this seems highly unlikely if the distance involved was large given the quantity involved. It is possible that, as the group moved about the countryside in pursuit of game or to take advantage of the availability of seasonal fruits and vegetables, that they took the time to pick up some better quality flint if it was available. An intriguing possibility is that some sort of exchange mechanism was worked out with one or more neighbouring groups. Small parties, perhaps amounting to no more than a single family, scattered thinly on the landscape would have had to depend on good relations with others in order to survive. It seems highly probably that regular meetings with other groups took place among neanderthals as they certainly did among more modern humans. For one thing, they needed a way to resolve disputes— particularly over territorial range— and to exchange information. Good relationships were strengthened by the exchange of commodities such as flint.

It is suspected that many of these sites, particularly the ones located at or very near flint sources, were specialist ‘factory’ sites but this is almost impossible to prove. Such things as the absence of faunal remains or well-used hearths would suggest at least the possibility of such sites as would the presence of numerous reduction flakes and cortex fragments but a scarcity of finished tools. As far as extraction is concerned, it is highly unlikely that any actual mining was involved. In the Perigord flint nodules are embedded in limestone formations and would have been very difficult to extract without proper picks. They were more likely have been the products of erosion and collected from the scree at the base of a slope or from river gravels.

Suggested Reading

| Bordes, François | (1961) | Typologie du Paléolithique ancien et moyen |

| Cartmill, M. & F. H. Smith | (2009) | The Human Lineage |

| Dibble, Harold J. & Paul Mellars | (1992) | The Middle Palaeolithic: Adaptation, Behaviour and Variability |

| Mellars, Paul | (1996) | The Neanderthal Legacy |

| Scarre, Chris (edit.) | (2018) | The Human Past (4th Edition) |

| Stringer, Christopher | (1993) | In Search of the Neanderthals |

| Wragg Sykes, Rebecca | (2020) | Kindred : Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art |

.jpg)

.jpg)