Olduvai Gorge (more correctly, Oldupai Gorge) is a steep-sided ravine nearly 50 km long which is located on the edge of the Serengeti Plain in Tanzania. It is part of the Great Rift Valley system that runs through east Africa and continues north through the Red Sea and the Jordan Valley. The system was created through the mechanism of plate tectonics, the splitting of the Arabian, Nubian and Somali plates—a process that began about 2 million years ago and is still ongoing at the rate of a little over 6 mm per year.

At the beginning of the Pleistocene the area was a basin formed by the uplifting of the volcanic highlands to the south and east, a product of these same tectonic forces. Initially, much of this basin was taken up by lake that was fed by streams flowing in from the south and east. This led to the creation of an extensive area of alluvial fan that was a very attractive environment for a wide range of animals, including hominins, and most of the archaeological discoveries have been made there. Although the lake eventually dried up over a million years ago, sediments continued to wash into it until they had accumulated to a thickness of almost 100 metres. This steady deposition was interrupted on occasion by episodes of activity from nearby volcanoes of Olmoti and Kerimasi, which appear as layers of ‘tuff’ (ash ejecta). These contain material which can be dated using radioactive isotopes—it was here that the potassium-argon (K-Ar) method was first tried out—and therefore can provide approximate dates for the material sandwiched in between them.

Google Earth view of Olduvai Gorge

The main gorge and the side gorge that runs into it were created over the course of the last 200 thousand years by downcutting stream activity combined with faulting, which gives us a natural cross-section of the geological sequence and exposing archaeological material and the fossils that had been buried hundreds of thousands of years before.

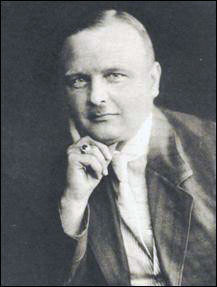

Hans Reck

Their potential for palaeontological and anthropological information was first made apparent in 1911 when a German entomologist named Wilhelm Kattwinkel who, so it is said, almost fell into the main gorge while chasing butterflies. While he was there, he collected a small number of animal fossils which he brought back to Berlin—Tanzania at the time was known as German East Africa. They attracted the attention of a young geologist named Hans Reck who organized an expedition to return to the gorge in 1913. He was able to recognize five distinct units which he numbered (starting at the bottom) Beds I-V lying on top of a lava flow of igneous rock.

he brought back to Berlin—Tanzania at the time was known as German East Africa. They attracted the attention of a young geologist named Hans Reck who organized an expedition to return to the gorge in 1913. He was able to recognize five distinct units which he numbered (starting at the bottom) Beds I-V lying on top of a lava flow of igneous rock.

In the course of his investigations Reck collected over 1,700 fossils, predominantly the remains of extinct prehistoric animals from the Pleistocene. In December 1913, however, one of his workers came across a bone protruding from the face of Bed II. Reck himself directed the excavation of the rest of the skeleton which turned out to be that of an anatomically modern human. He took the skull back to Germany the following spring and published an article in which he claimed that it was probably about 150,000 years old although this was widely disputed in scholarly circles. He returned to east Africa later that year and, despite the outbreak of World War I, managed to conduct excavations in other parts of the colony. But in 1916 the allies invaded and Reck, who had volunteered to command a native contingent, was taken prisoner the following year. When the war ended, he was released from internment and returned to Berlin. By the terms of the Versailles Treaty, the colony, henceforth known as Tanganyika, was mandated to Britain.

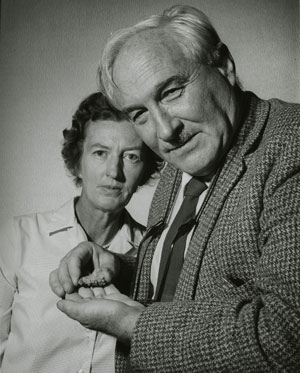

The Leakeys

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey was born in 1903, the son of English missionaries who worked among the Kikuyu people of central Kenya. Having spent his childhood among the Kikuya, learning their language, hunting and playing with their children and eventually being initiated into their tribe, he was sent back to England to finish his education. He ended up at St. John’s College, Cambridge where he matriculated in 1922 intending to go back to Africa as a missionary but, after participating in an expedition after dinosaur fossils in the newly acquired territory of Tanganyika in 1924, he decided to take up anthropology and archaeology, subjects in which he was much interested as a boy, and make them his career. In the late 1920s, he made frequent trips to Africa and conducted dozens of excavations before returning to Cambridge to complete his PhD, which he received in 1930.

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey was born in 1903, the son of English missionaries who worked among the Kikuyu people of central Kenya. Having spent his childhood among the Kikuya, learning their language, hunting and playing with their children and eventually being initiated into their tribe, he was sent back to England to finish his education. He ended up at St. John’s College, Cambridge where he matriculated in 1922 intending to go back to Africa as a missionary but, after participating in an expedition after dinosaur fossils in the newly acquired territory of Tanganyika in 1924, he decided to take up anthropology and archaeology, subjects in which he was much interested as a boy, and make them his career. In the late 1920s, he made frequent trips to Africa and conducted dozens of excavations before returning to Cambridge to complete his PhD, which he received in 1930.

In 1927 he travelled to Munich to examine the remains of “Oldoway Man” that Reck had discovered before the war, returning in 1929 for another look. In the course of his visit, Reck showed him the ‘geological’ specimens he had brought back at the same time. Among them Leakey recognized a number that were man-made, including chopping tools of the sort that had been recovered in Europe and dating to the Lower Palaeolithic. He invited Reck to join him on a new expedition to Olduvai where they arrived in September 1931. Archaeological material, in the form of hand axes and other stone tools, were soon forthcoming. Leakey was also able to confirm Reck’s estimate of the age of Oldoway Man, suggesting that it might even be much older. He also confirmed Reck’s interpretation of the geology of the gorge, eventually publishing them in his first Olduvai monograph in 1951.

At the time, Leakey was married to his first wife Frida (née Avern) whom he had met on an earlier visit to Kenya—it  was she who discovered the gully that bears her initials (FLK) and where so many important fossils were discovered—but by 1934 he was involved in a relationship with Mary Nicol, an illustrator and archaeologist who had trained with Mortimer Wheeler. She also accompanied him to Tanganyika and became an invaluable co-worker and director of excavations. They eventually married in 1936, after Frida Leakey divorced her husband and together they had three sons: Jonathan (1940), Richard (1944), and Philip (1949); and a daughter who died in infancy. Of their sons, only Richard pursued a career in archaeology and made a number of crucial discoveries in Ethiopia and Kenya.

was she who discovered the gully that bears her initials (FLK) and where so many important fossils were discovered—but by 1934 he was involved in a relationship with Mary Nicol, an illustrator and archaeologist who had trained with Mortimer Wheeler. She also accompanied him to Tanganyika and became an invaluable co-worker and director of excavations. They eventually married in 1936, after Frida Leakey divorced her husband and together they had three sons: Jonathan (1940), Richard (1944), and Philip (1949); and a daughter who died in infancy. Of their sons, only Richard pursued a career in archaeology and made a number of crucial discoveries in Ethiopia and Kenya.

Louis and Mary worked as a team at Olduvai and other sites during the 1930s through to the 1950s. However, funding was difficult to organize and the times were turbulent to say the least so their expeditions during this period were intermittent and brief. Nevertheless, they collected a huge number of man-made artefacts and the fossil remains of prehistoric fauna—over 2,000 stone tools and 3,500 fossilized animal bones were found in the FLK locality alone. Traces of early hominins proved elusive however. That all changed in dramatically in 1959 with the discovery of Paranthropus boisei.

Stratigraphy

Although Reck was prevented from completing his study of the geology of the gorge, it was accepted as the basis for a more detailed analysis by Richard Hay published in 1976. Hay kept the original basic divisions and nomenclature except for Bed V, which he divided into three separate levels—the Masek, Ndutu, and Naisiusiu Beds. All of levels contain cultural material along with fossil evidence that covers nearly the whole span of human development.

The bedrock is made up of basaltic lava flows resulting from the tectonic activity that marked the creation of the Rift Valley System and the end of the Pliocene.

Bed I: ranges from 20-45 metres in thickness and is made up of clay and sandstone sediments, sub-divided by four distinct deposits of tuff (Ib-f) laid down at intervals between about 2.03 and 1.75 million years ago. The climate was cooler and moister then, with an annual average temperature of 16°C vs. 22°C today; and an average rainfall of ca. 800 mm per annum vs. 566mm today. The trend to a warmer, drier climate began to take hold almost from the start. The ancient lake gradually began to shrink until, by the end of the period, it had almost disappeared. Initially, the margins of the lake were swampy while the surrounding countryside was extensively forested but, by the end of the period, it was similar to the savannah we see today in the Serengeti. This is indicated by a steep decline in arboreal pollen and a change in the fauna from shade-loving to open-loving species. Oldowan tools are found from top to bottom, along with the fossilized remains of Paranthropus boisei (a species of robust australopithecine) and Homo habilis, the first known human species.

Bed II: is a deposit of clay and sandstone sediments varying from 21-35 metres in thickness that was formed between 1.75 & 1.2 million BP. The lake and swampland that was such a feature of Bed I disappear during this period and there is a change to from forest to open grasslands as the climate becomes warmer and drier—something reflected in the faunal remains as well with a trend away from shade-loving species to those that thrived in the open. Bed II contains a lot of cultural artefacts, including ‘manuports’ (unworked stone that had been brought to the site through human agency) as well as a chert quarry

Oldowan tools throughout and Acheulean handaxes in the upper levels. Unfortunately, not a lot of fossils have been found. Remains of P. boisei occur throughout but, although H. habilis appears in the lower bed, it is entirely absent in the upper part and is replaced by a later hominin, H. ergaster.

Bed III: consists of 6-10 metres of alluvial deposits, red clays and sandstone, laid down by streams flowing in from the south and east starting beginning 1.4 million years ago. As far as evidence of human activity is concerned there is little apart from a few cranial fragments of H. ergaster along with some isolated Acheulean tools.

Bed IV:In contrast to Bed III, Bed IV receives its deposits of alluvium from streams flowing in from the north and west and ranges from 5-8 metres in thickness. The material is essentially the same in both and they are really only distinguishable in the eastern part of the gorge. Some 500 stone tools, including handaxes and cleavers along with the fossilized pelvis and femur belonging to an individual H. ergaster.

Bed ‘V’: The three uppermost beds were laid down over the course of the last million years or so and consists of both alluvial and aeolian (windborne) deposits. The most significant change was the faulting visible in the Ndutu Bed at around 400,000 BP which led to downcutting by stream action, substantial erosion and the creation of the gorge as we know it today. Some Acheulean material has been found in the Masek Bed but otherwise very little afterwards until the Naisiusiu Bed (22-15,000 BP) when the remains of Homo sapiens were discovered along with Later Stone Age tools.

Fossil Hominins

The two gorges have a good number of gullies, korongo in Swahili, running into them and it is in these that most of the archaeological discoveries have been made. Archaeological sites and find spots are labelled with the initials of the person who discovered it plus the letter K for korongo—for example, MNK=Mark Nicol Korongo. Fossil hominins receive the designation OH (Olduvai Hominin) plus a numeral indicating the order in which they were found.

Paranthropus boisei

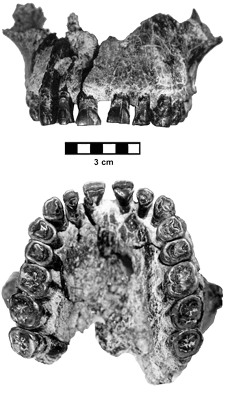

OH 5

In 1959, Mary Leakey made the first important fossil discovery near the top of Bed I in the FLK (Frida Leakey Korongo) locality. It was the almost complete cranium dating to between 1.85-1.79 million years ago. It was a specimen unlike any other discovered thus far in Africa, only the mandible (lower jaw) was missing. Based on tooth eruption, this skull is thought to be that of a juvenile but, even so, the relatively small capacity of the brain case (530 cc) suggested it was much closer to australopithecus than homo.

Two views of the reconstructed skull of OH 5

The structure of the skull suggests a lifetime of chewing tough, fibrous foods such as tubers. It is characterized by a receding forehead and a prominent brow ridge and it narrows drastically right behind the eye sockets (postorbital constriction), probably to accommodate enlarged facial muscles. There is also a sagittal crest running along the top, providing a large platform for their attachment. Taken together with the flared cheek bones and large molars, everything suggests a lot of long, hard chewing. The subsequent discovery elsewhere of more remains, including lower jawbones, have only confirmed this impression.

Louis Leakey thought these features to be sufficiently unique to label it as a distinct genus and named it Zinjanthropus boisei (‘Zinj’ for short) but it was subsequently classified as one of the robust australopithecines. It was renamed Paranthropus(or Australopithecus) boisei and is considered the holotype of the species. They were evidently a feature of the landscape. Part of the problem of classification is because fossils that include both cranial bones and those of the rest of the skeleton are virtually nonexistent. Most of the other postcranial bones that have been found could be reasonably assigned to either P. boisei or H. habilis. Only OH 80, which was discovered in 2010 and includes arm and leg bones as well as teeth, can be assigned to the former with any confidence. It would seem to indicate that an adult male stood about 1.56 metres tall and weighed in at about 62 kg. The lengthy arm bones suggest that they spent much of their time in the trees. Oldowan tools were found nearby, although not in direct association, and the Leakeys assumed that ‘Zinj’ had made them but that assumption was cast in doubt by discoveries made the very next year.

Homo habilis

OH 7

In November 1960 Jonathan Leakey, the eldest son of Mary and Louis, spotted the broken remains of the lower mandible (jawbone) of a prehistoric hominin in the Level III deposits of Bed I at locality FLK about 275 metres from the spot where Zinj was found. In the first ever use of the potassium-argon (K-Ar) method, the deposit was dated to about 1.75 million years ago. The jawbone still had 13 teeth attached, including unerupted wisdom teeth. Further investigation yielded two parietal bones, which together  formed the sides and rear part of the cranium, along with a 21 bones (phalanges, trapezium and scaphoid) belonging the hand and wrist and an isolated maxillary (upper) molar. All of these evidently belonged to the same individual, a juvenile (assumed to be a male) who was nicknamed ‘Jonny’s Boy’ in honour of his discoverer.

formed the sides and rear part of the cranium, along with a 21 bones (phalanges, trapezium and scaphoid) belonging the hand and wrist and an isolated maxillary (upper) molar. All of these evidently belonged to the same individual, a juvenile (assumed to be a male) who was nicknamed ‘Jonny’s Boy’ in honour of his discoverer.

The skull fragments suggest a brain size of about somewhere between 665-675 cc—compared to 530 cc for the P. boisei skull recovered the previous year. The mandible was more U-shaped than V-shaped and the chin was less prominent than was the case with australopithecines. The teeth were different too. The incisors and canines were larger and the molars were smaller than those of P. boisei and more round than oval. The phalanges (finger bones) show a mixture of ape-like and human features. They are slightly curved, similar to those of modern chimpanzees—well-adapted for swinging from branch to branch and hanging above the forest floor. The hand is wider, the thumb is larger and the fingertips are broader and flatter than those of other, contemporary hominins and gave them a more precise grip which would come in handy when it came to making stone tools. Unfortunately, there was not enough evidence to confidently determine the gender of this particular individual—there were no other fossils with which to make comparisons—however, the unerupted wisdom teeth suggest an age of about 12 or 13.

Taken altogether, the evidence convinced Louis Leakey that the finds represented a new species, which he classified as Homo habilis (‘handy man’). OH 7 became the type fossil.

OH 8

In that same year Louis Leakey found the almost complete remains of a foot right next to OH 7 but apparently not part of the same individual. The phalanges were missing as were the tips of the  metatarsals. Opinion is divided as to whether the latter was the result of gnawing by scavengers or because the bones had not yet fused. If the latter, it would suggest the individual was a juvenile. Part of the calcaneus (heel bone) was also missing but otherwise the rest of the bones were all present. Altogether, the foot shows a mixture of ape-like and human features. The long toes would have made climbing fairly easy but the apparent longitudinal arch of the foot was well-adapted for bipedal locomotion as well. It was the enhanced ability to walk upright that persuaded Leakey to classify it as H. habilis.

metatarsals. Opinion is divided as to whether the latter was the result of gnawing by scavengers or because the bones had not yet fused. If the latter, it would suggest the individual was a juvenile. Part of the calcaneus (heel bone) was also missing but otherwise the rest of the bones were all present. Altogether, the foot shows a mixture of ape-like and human features. The long toes would have made climbing fairly easy but the apparent longitudinal arch of the foot was well-adapted for bipedal locomotion as well. It was the enhanced ability to walk upright that persuaded Leakey to classify it as H. habilis.

OH 24

.jpg) More information on the structure of the skull of H. habilis became available in 1968 when Peter Nzube discovered most of a cranium and a few teeth in a deposit near the base of Bed I and dated to about 1.85 million BP. Unfortunately, it had been badly crushed and cemented with a coating of limestone but, after a painstaking reconstruction process undertaken by Ron Clarke, it was possible to give it a thorough examination. There was still considerable distortion and the estimated cranial capacity, 590-600 cc, might be attributed to this. The lower part of the face is prognathic, which means it projects forward, but not to the same extent as australopithecines. The back molars had erupted so presumably the skull was that of an adult. However, because they showed no sign of wear the owner died not long after they appeared. The maxillary arch (roof of the mouth) is U-shaped.

More information on the structure of the skull of H. habilis became available in 1968 when Peter Nzube discovered most of a cranium and a few teeth in a deposit near the base of Bed I and dated to about 1.85 million BP. Unfortunately, it had been badly crushed and cemented with a coating of limestone but, after a painstaking reconstruction process undertaken by Ron Clarke, it was possible to give it a thorough examination. There was still considerable distortion and the estimated cranial capacity, 590-600 cc, might be attributed to this. The lower part of the face is prognathic, which means it projects forward, but not to the same extent as australopithecines. The back molars had erupted so presumably the skull was that of an adult. However, because they showed no sign of wear the owner died not long after they appeared. The maxillary arch (roof of the mouth) is U-shaped.

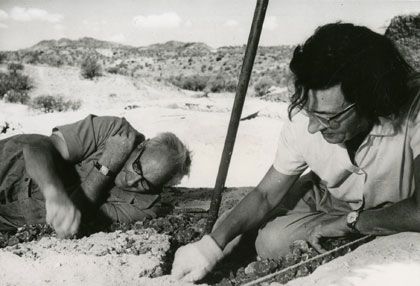

OH 62

A better idea of the size and stature of H. habilis is provided by OH 62, whose partial skeleton was uncovered by Tim White in 1986 in the FLK locale, Bed I. There were over 300 fossil fragments including elements of the cranium and both the forelimb and hindlimb (AKA: the arm and the leg). The palate is well-preserved and the size and shape of the teeth are closer to those from H. habilis rather than P. boisei. The forelimbs include parts of the humerus, the radius and the ulna; while the hindlimbs are represented by parts of a proximal femur (thigh bone) and parts of a proximal tibia (shin bone).  Together, they should give a good indication of body size and the relative proportions of the legs and arms. The evidence suggests that the latter were changing, with the legs becoming longer and the arms a little bit shorter. In other words, more suited to walking upright on the ground than to a life swinging from branch to branch up in the trees—although still capable of doing so.

Together, they should give a good indication of body size and the relative proportions of the legs and arms. The evidence suggests that the latter were changing, with the legs becoming longer and the arms a little bit shorter. In other words, more suited to walking upright on the ground than to a life swinging from branch to branch up in the trees—although still capable of doing so.

This particular individual is assumed to have been female, and is estimated to have stood about 100-120 cm tall and weighed somewhere between 20-35 kg. That is assuming she had australopithecine proportions. If she had more human proportions she would have stood closer to 150 cm tall. It is assumed that there was marked sexual dimorphism, with males much larger than females, but there is no real evidence for that.

OH 65

In the 1995 a team led by Robert Blumenschine, who were investigating the western portion of Bed I of the main gorge—an area that had received scant attention until then—unearthed the upper jaw (maxilla) of an early hominin, complete with teeth, along with part of the lower face. There were stone tools and fossilized animal bones, some of which have characteristic marks of butchery, associated with it. The suggested date, based on its context, is about 1.8 million BP. It is generally corresponds to the mandible belonging to OH 7 and is therefore classed as H. habilis—although some believe it more closely matches a closely related species, H. rudolfensis.

The most interesting thing about this particular fossil is that the front teeth bear striations similar to those found on Neanderthal teeth, which are thought to be caused by clenching a piece of meat in one’s mouth and slicing it with an edged stone tool. In this case, the pattern of the striations suggest the owner was right-handed.

Homo Ergaster

OH 9

1960 also saw the discovery of another key fossil that appeared not far away from Jonny’s Boy and Zinj and was found by Louis Leakey’s team in the upper levels of Bed II in locality LLK (Louis Leakey  Korongo) which has been dated to roughly 1.47 million BP. It proved to be part of a braincase, the frontal bone and parts of both parietals. It was long and low, like those of the Homo erectus fossils that had been found years earlier in China and Indonesia—Peking Man and Java Man. Its cranial capacity was judged to be 1067 cc, larger than any H. erectus that had been unearthed so far and it had an enormous mid supra-orbital torus (‘brow ridge’), some 18.5 mm thick, and the occipital torus at the back of the skull was similarly thick. In addition, there was no evidence of keeling, so most scholars would classify OH 9 as a new species, which is now most commonly known as Homo ergaster (“working man”), a species so far located mainly in Africa. There is still some debate as to the relationship between H. erectus and H. ergaster, however, with some scholars viewing them both as essentially the same species, H. erectus, while others regard the latter as a local variant rather than an independent species, which they have designated H. erectus ergaster.

Korongo) which has been dated to roughly 1.47 million BP. It proved to be part of a braincase, the frontal bone and parts of both parietals. It was long and low, like those of the Homo erectus fossils that had been found years earlier in China and Indonesia—Peking Man and Java Man. Its cranial capacity was judged to be 1067 cc, larger than any H. erectus that had been unearthed so far and it had an enormous mid supra-orbital torus (‘brow ridge’), some 18.5 mm thick, and the occipital torus at the back of the skull was similarly thick. In addition, there was no evidence of keeling, so most scholars would classify OH 9 as a new species, which is now most commonly known as Homo ergaster (“working man”), a species so far located mainly in Africa. There is still some debate as to the relationship between H. erectus and H. ergaster, however, with some scholars viewing them both as essentially the same species, H. erectus, while others regard the latter as a local variant rather than an independent species, which they have designated H. erectus ergaster.

OH 12

In 1962 fragments of a hominin skull were found on the surface of Bed III at locality VEK by Margaret Cropper. In general, the reconstructed skull resembles that of OH 9 except that it is much smaller with a cranial capacity of only about 750 cc. It is also several hundred thousand years younger, dating to somewhere between 830-620 thousand BP and making it the latest of the species to be discovered so far.

OH 28

OH 28, discovered by Mary Leakey in 1970 at locality WK (Wayland’s Korongo), represents the only postcranial remains found at Olduvai thus far consisting of a femur and part of the hip bone. Their examination gives anthropologists a better idea of how H. ergaster stood and moved about. The hip is very much like that of a modern human, suggesting that H. ergaster normally walked upright on both legs.

Ongoing Research

Louis Leakey died in October 1972 but work continued under the leadership of Mary Leakey, both at Olduvai and the nearby site of Laetoli, where her team discovered a well-preserved set of hominin footprints. She died in Nairobi in 1996.

In the meantime, research has continued under the auspices of the Cultural Antiquities Department of Tanzania, which has hosted expeditions from around the world. In 1979, Olduvai Gorge became a UNESCO World Heritage Site, part of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area.

Suggested Reading

| Blumenschine, Robert et al | 2003 | Late Pliocene Homo and Hominid Land Use from Western Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. Science, 299 |

| Hay, Richard | (1976) | Geology of the Olduvai Gorge |

| Leakey, Louis S.B. | (1951) | Olduvai Gorge: A Report on the Evolution of the Hand-Axe Culture in Beds I–IV |

| (1965) | Olduvai Gorge: A Preliminary Report on the Geology and Fauna, 1951–61 | |

| (1970) | Olduvai Gorge, 1965–1967 | |

| (1974) | By the evidence: Memoirs 1932-1951 | |

| Leakey, Mary D.N. | (1971) | Olduvai Gorge: Excavations in Beds I and II. 1960-1963 |

| (1979) | Olduvai Gorge: My Search for Early Man | |

| (1984) | Disclosing the Past | |

| Leakey, Mary D.N. & Derek Roe | (1995) | Olduvai Gorge: Excavations in Beds III, IV and the Masek Beds, 1968-1971 |

| Scarre, Chris (edit.) | (2018) | The Human Past (4th Edition) |

| Shea, John J. | (2017) | Stone Tools in Human Evolution |