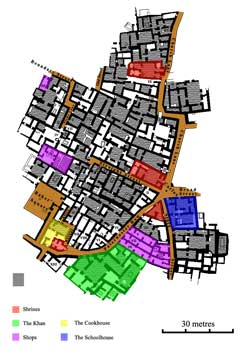

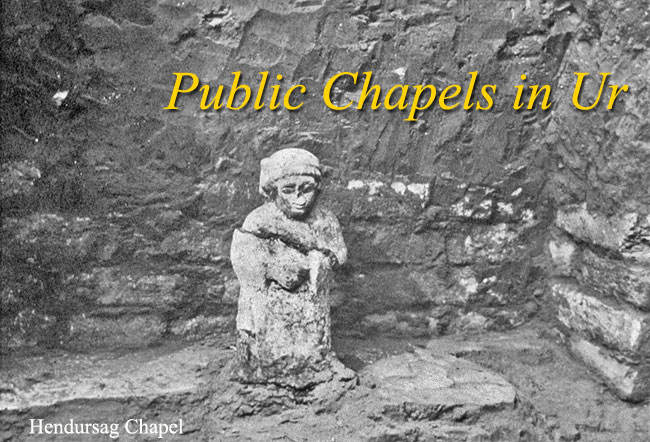

Shrines are found at prominent locations within the excavated area and especially intersections. They were designed to meet the religious needs of ordinary people rather than the city as a whole  and were much more open and accessible than the major temples. Where the name of the deity is known (Hendursag or Nin-shubur) it is of minor rank. Their cult was maintained by private charity and not by state funds. The buildings are distinguished from ordinary homes by their somewhat grander entrances—elaborate doorways decorated with reveals and guarded by terracotta images of protective demons (like the one of Humbaba shown left). Moreover, shrines invariably sit at a higher level than the street while houses are generally lower.

and were much more open and accessible than the major temples. Where the name of the deity is known (Hendursag or Nin-shubur) it is of minor rank. Their cult was maintained by private charity and not by state funds. The buildings are distinguished from ordinary homes by their somewhat grander entrances—elaborate doorways decorated with reveals and guarded by terracotta images of protective demons (like the one of Humbaba shown left). Moreover, shrines invariably sit at a higher level than the street while houses are generally lower.

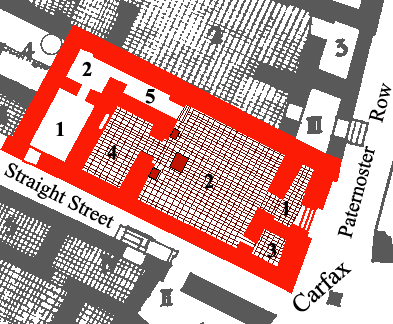

The basic form of such chapels consisted of a small open courtyard with a small room which served as the shrine. A good example is the so-called Bazaar Chapel, at the intersection of Bazaar Alley and Paternoster Row. But any number of other rooms could be added, depending on the importance of the deity and the generosity of his or her worshippers. These might include lobbies, antechambers and storerooms.

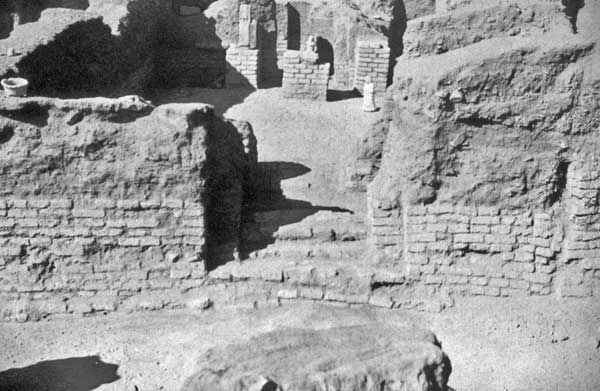

The Hendursag Chapel at the corner of Straight Street and Church Lane, fronting on the open space Woolley called Carfax, is a typical example. A short flight of steps led through the front door and into a small lobby which opened directly onto the courtyard. On the right was a deep alcove where ablutions were typically performed, just like in a private home. Next to the lobby was a small storage room, which contained cult paraphernalia and objects dedicated as votive offerings to the god.

Interior of the Hendursag Chapel

The cult room itself lay on the opposite side of the courtyard. A brick altar stood in the courtyard in front of the entrance and there was a pedestal on either side. Burnt offerings were placed on the  altar while the pedestals, one of which had been hollowed out at the top to form a bitumen-lined cup, was used for libations (liquid offerings). Against the northeast wall, a short distance from the east corner, there was a gap in the pavement measuring 1.20 x 0.65 metres which may have been the site of a brick installation, possibly a statue base. In fact, the broken statue of a goddess was found lying in the courtyard a short distance away (left). Woolley also found a number of other objects including the skull of a water buffalo and grinding equipment. More grinding equipment was found in the passage (Room 5) running from the northern corner of the court. This corridor led to a pair of rooms with their own entrance off Straight Street (No. 1 Straight Street, Rooms 1 & 2) which probably served as a robing room for the priests and a waiting room.

altar while the pedestals, one of which had been hollowed out at the top to form a bitumen-lined cup, was used for libations (liquid offerings). Against the northeast wall, a short distance from the east corner, there was a gap in the pavement measuring 1.20 x 0.65 metres which may have been the site of a brick installation, possibly a statue base. In fact, the broken statue of a goddess was found lying in the courtyard a short distance away (left). Woolley also found a number of other objects including the skull of a water buffalo and grinding equipment. More grinding equipment was found in the passage (Room 5) running from the northern corner of the court. This corridor led to a pair of rooms with their own entrance off Straight Street (No. 1 Straight Street, Rooms 1 & 2) which probably served as a robing room for the priests and a waiting room.

The cult room (Room 4) was closed by a pair of doors— a heavy wooden door which swung  outwards and a light screen door (a wooden frame with a panel of reeds, the impression of which was found in the soil, left) which opened inwards. The entrance was decorated with reveals. There was a niche in the wall opposite which contained a mud brick platform for the cult statue. The latter had been broken in antiquity and crudely mended using bitumen. The feet were missing and it had been embedded in the whitewashed mud base to keep it upright. A number of tablets found scattered on the floor deal with, among other things, the scheduling of a number of priests. They seem to indicate that the chapel and its staff were supported from the revenues of property owned by the shrine and not by the city.

outwards and a light screen door (a wooden frame with a panel of reeds, the impression of which was found in the soil, left) which opened inwards. The entrance was decorated with reveals. There was a niche in the wall opposite which contained a mud brick platform for the cult statue. The latter had been broken in antiquity and crudely mended using bitumen. The feet were missing and it had been embedded in the whitewashed mud base to keep it upright. A number of tablets found scattered on the floor deal with, among other things, the scheduling of a number of priests. They seem to indicate that the chapel and its staff were supported from the revenues of property owned by the shrine and not by the city.

The only other deity that can be identified in any of the shrines was Nin-shubur whose statue was found in the chapel at No. 1 Paternoster Row (also facing onto Carfax. The figure of a ram, which was apparently meant to be mounted on a pole, was found at No. 11 Church Lane so Woolley called it the “Ram Chapel”. Generally speaking, the excavated chapels are very small and somewhat irregular in their layout. Like the buildings around them (and unlike the great civic temples) they had to accommodate themselves to the space available. In the case of Bazaar Chapel, the corner of No. 14 Paternoster Row was torn down to provide space for it.

|

Left: Terracotta plaque of a worshipper with a sacrificial goat (left) and the terracotta head of an unknown god. Old Babylonian Period