Ii. the First Apes

Miocene Epoch (c.23-5.3 million BP)

Tectonic forces continued to play an enormous role in the formation of the African continent during the Miocene. In the northeast there were a number of plates operating—the Arabian, the Nubian, the Somalian and the Eurasian. Their movements led to the formation of a land-bridge between Eurasia and Africa and the transfer of species from one to the other. It also led to rifting along the whole length of east Africa, from the Red Sea to Malawi. The uplifting of highlands gradually changed the prevailing weather patterns so that this part of Africa became gradually drier and the vegetation had to adapt accordingly.

Elsewhere in Africa, the picture is somewhat murky, mainly due to the difficulties presented by the environmental conditions, in the Congo basin, for example, and the lack of datable material—particularly in South Africa.

Plate Tectonics and the East African Rift System

Computer rendering of Albertine (Western) Rift Valley. © Christopher Horman

Soon after the beginning of the Miocene, about 20 million years ago, it is thought that a plume of hot magma welled up from the underlying mantle and put pressure on the earth’s crust in East Africa. The upthrust caused stretching and cracking and created a series of parallel rift valleys (graben) where the crust has dropped and mountain ranges (horst) where it has risen—a process known as ‘faulting’. The process is ongoing and led to the creation of the East African Rift  System, which now extends from Jordan, through the Red Sea and south to Mozambique, a distance of over 4,5oo kilometres. There are two major branches, the Eastern and Western Rifts, both of which are or have been the site volcanic activity and contain both active and dormant volcanoes. They diverge in Ethiopia and run roughly parallel before reuniting in Malawi. Volcanic activity has subsided in the last 2 million years while the effects of wind and water have softened the features of the landscape somewhat.

System, which now extends from Jordan, through the Red Sea and south to Mozambique, a distance of over 4,5oo kilometres. There are two major branches, the Eastern and Western Rifts, both of which are or have been the site volcanic activity and contain both active and dormant volcanoes. They diverge in Ethiopia and run roughly parallel before reuniting in Malawi. Volcanic activity has subsided in the last 2 million years while the effects of wind and water have softened the features of the landscape somewhat.

The widening of the rift and consequent subsidence of the valley floors is the result of the gradual separation of three plates, with the Somalian Plate and the Arabian Plate moving away from the rest of Africa at the rate of 6-7 mm per year. The point of intersection is in the Afar Region of Ethiopia, where it forms what is known as the Afar Triangle. The whole process has proved to be a boon for palaeoanthropologists as it exposes layers that are millions of years old on the slopes of the valleys. That is precisely where the fossils are found.

The tectonic uplift has had a profound and ongoing affect on the climate and vegetation of East Africa. Previously it benefited from both the Atlantic and Indian Ocean monsoons and was part of an area of extensive rainforest that extended right across the continent. However, the steady uplift split the region in two and created rain shadows on either side, with the bulk of the precipitation falling on the slopes of the mountains. By the end of the Miocene, the topography comprised two ranges flanking a progressively arid central rift valley. The rainforest was disappearing by now and was being replaced by C4 grasslands, according to carbon isotope analysis.

A major contributing factor to the increased dryness was the result of plate tectonics in another part of the world, the collision of the Indian Plate with the Eurasia which began some 70 million years ago in the Cretaceous Period. This caused the upthrust of the Tibetan Massif which, along with the Eastern Rift Shoulder range, led to the creation of what is known as the ‘Findlater Jet’. This is a narrow low-level, atmospheric jet that develops during the Southwest monsoon and blows diagonally across the Indian Ocean, diverting the monsoons in that direction, greatly reducing the amount of rainfall in East Africa.

Miocene African Fauna. © Mauricio Anton

In addition to increased aridity during the Miocene, there was also a sharp decrease in atmospheric carbon dioxide to levels more or less the same as today’s (c. 400 ppm) which contributed to the slow but steady expansion of grassland. The grasslands contained areas of scrub bush as well as stands of trees and, wherever there was permanent water, there were areas of closed forest. This type of landscape is known as savannah (or savanna) and is characterized by seasonal fluctuations in rainfall, with alternating wet and dry seasons. The latter became more prolonged and extreme as time passed,  putting a severe strain on the plants and animals that depended on water to survive. Initially these savannahs were characterized by C3 plants including grasses but, as drying process continued over the next several million years, they slowly gave way to C4 grasses which were better equipped to deal with the changing circumstances.

putting a severe strain on the plants and animals that depended on water to survive. Initially these savannahs were characterized by C3 plants including grasses but, as drying process continued over the next several million years, they slowly gave way to C4 grasses which were better equipped to deal with the changing circumstances.

The new animals on the scene included a number that were able to flourish on the savannah, both herbivores and the carnivores that preyed on them. The Early and Middle Miocene were characterized by a number of very large animals, among them the Rhinocerotidae and Hippopotamidae, both of which were newly arrived from Eurasia. Mammals that have since become extinct include a relative of modern tapirs known as the chalicotheres, a huge beast which used its large claws to tear branches down from the trees; and the sivatheres a short-necked member of the giraffid family with bony antlers antlers (Sivatherium giganteum). Wear analysis of their teeth indicates that they were all browsers who ate mainly leaves and fruit, rather than grazers who cropped grass.

The dominant predators of the Oligocene and Early Miocene belong to an extinct group known as creodonts and are classed separately from the Order Carnivora which superseded them. The first to appear were the Hyaenidae of which there were at least 5 families. At first, they were all dog-like animals who chased down their prey but by the onset of the Pliocene these had been replaced by animals with bone-crushing jaws, more akin to modern species. The first big cats to arrive were sabretooths, which appear in the Late Miocene. Meganterion had the typical muscular forelimbs and dagger-like canines seemingly designed to penetrate the thick skins of some of the larger prey such as young rhinos or elephants. Homotherium, who first shows up in the Pliocene, seems to have been an ambush predator operating in woodlands where flight was more difficult. Lokotunjailurus emageritus was more gracile and perhaps better suited to chasing down its prey.

The Spread of Grasses

Much of the living biomass of grasses is found underground in the form of roots and buds, which means that much of it survives the brush fires that characterize the dry season and remove much of the above ground growth. Periodic fires are necessary to clear away the old, dead growth and permit new growth to take its place. Single or multiple stems with nodes and attached leaves extend upwards from the crown of the roots, terminating in a cluster of tiny flowers that turn into seeds. Some varieties extend their stems sideways, along the ground where their nodes put down roots and send up their own stems. Their extensive root systems mean that they can out compete trees for available water and make it difficult for young trees to get established.

Savannah grassland in Burkina Faso

Grasses are divided into two groups depending on the method used to photosynthesize sunlight into carbohydrates, which can be stored or used as energy. This takes place in the chloroplasts within the leaves, absorbing infrared radiation, reflecting green light and ‘fixing’ the carbon. This involves the mediation of either a three-carbon (C3) molecule or four-carbon (C4) molecule. C3 plants are by far the most common but they only really thrive in temperate regions or areas with reduced sunlight and plenty of water. It is mainly the more efficient C4 grasses that thrive in the hot, dry, sunny conditions out in the open country while C3 plants, including some grasses along with leaves and fruit, are found predominantly in wooden areas. As a food source, however, the tropical grasses that gradually spread throughout the African savannah were somewhat wanting. Most of the nutrients were stored underground, and an enormous amount of foliage had to be consumed to extract what nutrition remained. C3 plants, on the other hand, were highly nutritious and easier to digest, but their availability was much more seasonal. An analysis of the carbon isotopes found in the bones and teeth, including fossilized ones, will show the proportion of each consumed in an animal’s diet.

In the Miocene, the grasses were mainly of the C3 variety but, as conditions became drier and the open areas expanded, C4 grasses came to the fore, becoming the dominant variety during the Pliocene and into the Pleistocene.

The main problems with depending on grass or leaves for nutrition is that huge quantities of it are required and the fact that they are very difficult to digest due to their high cellulose content. Breaking it all down into fatty acids that are usable requires microbial fermentation in the gut. In some species such as the equids and elephants, this is done by ‘hindgut fermentation’ which takes place in an enlarged colon and a chamber known as the cecum. In the case of ruminants, such as the bovids and giraffids, it takes place in a large chamber, the rumen, whereupon the forage is regurgitated and broken down some more by further chewing before being swallowed again. It then passes through two more chambers, the reticulum and the omasum before it reaches the stomach proper, the abomasum. There are advantages and disadvantages with both methods and, although all of these herbivores can both browse and graze, hindgut fermenters digest grass poorly and ruminants have trouble with leaves. The amounts of forage that had to be consumed and its seasonal availability tended to favour larger species, which require less nutrition for their body mass and are better able to survive prolonged dry seasons.

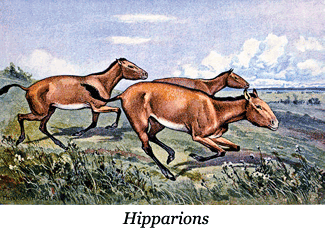

The earliest ruminants are thought to belong to the genus Eotragus appeared around 18 million years ago in Asia. They gave rise to the Bovidae, the ancestors of all horned, cloven footed grazers—wild cattle and buffalo (Bovini) and antelopes (Tragelaphini) as well as sheep and goats (Caprini)— which spread widely throughout Europe and North America as well as to Africa. Originally they were mainly browsers but, by about 10 million years ago, grazers began to appear in significant numbers and not long afterwards shift their diet to C4 grasses. This is shown from the ratio of carbon isotopes (13C vs. 12C) in the enamel and, in some cases, by the size and shape of their teeth. Hipparions (an early equid) were among the first to do this but were followed by White Rhinos (but not Black Rhinos), many of the bovids, some of the elephants and short-necked giraffes.

The First Apes (Family: Hominidae)

Apes begin to appear in the fossil record about 15 million years ago but, because they mainly inhabited the tropical rainforest, where preservation of fossils is virtually nil, little is known of their immediate antecedents. Some fossilized teeth have been found in East Africa,which may belong to ancestral gorillas and chimpanzees, but little else.

The most obvious characteristic that distinguishes them from monkeys is their lack of tails, which most quadrupeds use for balance. Instead, they had a number of shoulder adaptations needed for swinging through the treetops, a technique known as brachiation. They also have larger brains for their size than most other mammals, which means that they are better at communication and organization, but there is a price to pay for this. Big brains need time to fully develop, which means a longer gestation in the womb, an extended period of parental dependency, and delayed sexual maturity. For these reasons, births tend to be fewer and more widely spaced. Group survival depended on a longer reproductive lifespan among mothers and a reduced mortality rate for them and their offspring.

Most modern apes eat leaves and fruit and their dentition reflects that. Their canines are ‘designed’ to rip through the skin of ripening fruit and their molars were used slice and chop it into mulch. Some of them may include animal protein in their diet, normally in the form of insects, eggs and hatchlings. As rainfall levels decreased and became more seasonal during the late Miocene their preferred foods became unavailable for extended periods of time and adjustments had to be made in their food procurement strategies. Changing seasons meant that unripe fruit and the more succulent leaves were not to be found. It then became necessary to forage on the ground, gathering fallen fruit and nuts, digging for bulbs and tubers, or scrounging amid the leave litter for bugs and larvae. Cracking nuts, opening tubers and digging into termite mounds would have been greatly facilitated by the use of tools, an activity observed among modern chimpanzee communities.

As the savannah grew, the forests shrunk and they often needed to move from one stand of fruit-bearing trees to another, often separated by hundreds of metres which meant spending mo retime simply moving around and less time collecting food.  Increasingly, this meant crossing stretches of open country with ever-increasing distances. The method they devised is known as ‘knuckle walking’, which involved turning the forefoot over and sparing wear and tear on the ‘palm of the hand’. Chimps and gorillas are capable of a few steps in an upright posture, particularly when they are being aggressive, but that is not their habitual means of getting around.

Increasingly, this meant crossing stretches of open country with ever-increasing distances. The method they devised is known as ‘knuckle walking’, which involved turning the forefoot over and sparing wear and tear on the ‘palm of the hand’. Chimps and gorillas are capable of a few steps in an upright posture, particularly when they are being aggressive, but that is not their habitual means of getting around.

Although some apes, such as orangutans, are solitary creatures most African varieties tend to congregate in groups. For gorillas this might be as small as a dozen or so individuals lead by a dominant male; for chimpanzees, on the other hand, group size may consist of a hundred or more individuals, including a number of males competing for sexual partners. Group cohesion is maintained through the practice of mutual grooming to create social bonding. It is estimated the chimpanzees spend as much as 20% of the daylight hours engaged in this activity. Vocalization also plays a role, as it does for many other animals, and is useful for conveying basic information—danger signals, mating calls, etc.

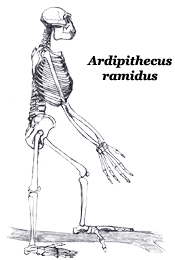

Towards the end of the Miocene about 7 million years ago, a subfamily of the hominidae (great apes) known as the Australopithecina or Homina (scholarly opinion is divided), split off from the rest  and ventured out of the forests and into the open. They were much better adapted for fully upright, bipedal walking and, in addition to being a more efficient means of covering ground, would have given them a better chance of spotting potential danger and freed the hands for other uses. They now seem to have developed the technique up in the trees, moving along the tops of branches, grasping them with their prehensile feet and using their ‘arms’ for balance and support. The latter were long, apelike and well-adapted for climbing too.

and ventured out of the forests and into the open. They were much better adapted for fully upright, bipedal walking and, in addition to being a more efficient means of covering ground, would have given them a better chance of spotting potential danger and freed the hands for other uses. They now seem to have developed the technique up in the trees, moving along the tops of branches, grasping them with their prehensile feet and using their ‘arms’ for balance and support. The latter were long, apelike and well-adapted for climbing too.

The earliest members of this group were Sahelanthropus tchadensis, Orrorin tugensis, Ardipithecus kadabba, and Ardipithecus ramidus, all of which emerged in the more forested areas of East and Central Africa. The location of the foramen magnum, the opening at the base of the skull through which the spinal cord passes in Sahelanthropus meant that its skull sat directly on top of the spine rather than projecting forward. The femur of Orrorin was longer and shared many features with later humans rather than apes. Changes in the articulation of the femora with the pelvis together with the upward tilting of the ilia, enabled a more or less permanent upright posture. With their opposable big toes, they would have had a rather slow and awkward gait but their usefulness when it came to tree-climbing was very useful in escaping predators or finding a place to nest for the night was a necessity for survival.

Further Reading

| Barham, L. & P. Mitchell | (2008) | The First Africans. African Archaeology from the Earliest Toolmakers to Most Recent Foragers |

| Clark, J. Grahame | (1969) | World Prehistory: A New Outline |

| Lewen, Roger | (2005) | Human Evolution. 5th Edition. |

| Maslin, Mark | (2017) | Cradle of Humanity |

| Maslin, Mark, et. al. | (2014) | East African climate pulses and early human evolution. Quaternary Science Review. |

| Owen-Smith, Norman | (2021) | Only in Africa. The Ecology of Human Evolution |

| Shea, John J. | (2017) | Stone Tools in Human Evolution |

-01.jpg)

.jpg)