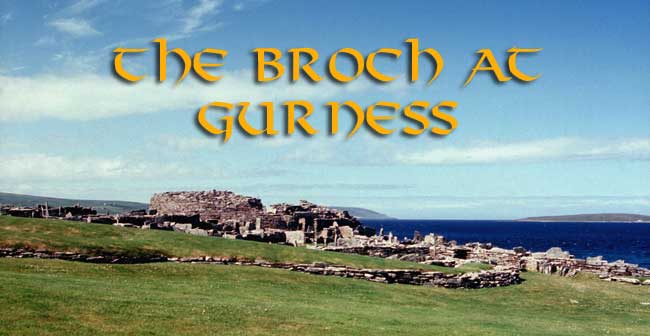

Gurness is one of a number of brochs found at fairly regular intervals along both shores of Eynhallow Sound, which separates the island of Rousay from Mainland. The site was excavated in the 1930s—under less than ideal circumstances. The first director, Hewat Craw, died suddenly after four seasons and his successor, J.S. Richardson was based in Edinburgh and rarely visited the site. Then the Second World War intervened and the site was not revisited until the 1950s and then only to consolidate the remains so that the site could be opened to the general public. The recording methods used were inadequate, to say the least and it has proved almost impossible to put any of the pottery or tools into their proper context. Little in the way of environmental information—animal bones, pollen samples, seeds, etc.—was recorded let alone kept. It was not until nearly a half century after the excavations had ceased that there was any sort of publication of the material, which was pieced together by John Hedges in 1987 (Bu, Gurness and the Brochs of Orkney, Part III).

Eynhallow Sound looking towards Rousay from Gurness

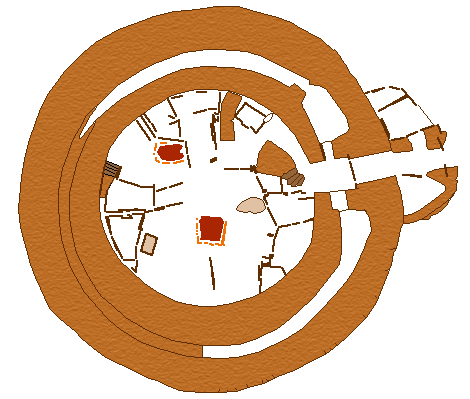

The broch tower only stands to a height of about 3.5 metres and, clearly, much of the stone has been robbed. Unusually for Orkney, it had a ground floor gallery that ran right around the inside of the wall. Unlike the ground galleried versions in the west of Scotland, the space was only accessible by squeezing through a narrow space at the back of each of the guard cells flanking the entrance, and clearly was not used as living space. Perhaps the intention was simply to reduce the amount of stone that was used or to help weatherproof the building and reduce heating costs as suggested above (Broch Design in Broch Architecture). Whatever the reasoning behind it, the plan  did not work as the weight of the walls caused dangerous stress on the lower parts of the wall, threatening to crack the lintel. The lower part of the gallery was hurriedly packed with stone to correct the problem. Access to the gallery was at the first floor level, some two metres above the ground, and must have been reached by wooden stairs or a ladder.

did not work as the weight of the walls caused dangerous stress on the lower parts of the wall, threatening to crack the lintel. The lower part of the gallery was hurriedly packed with stone to correct the problem. Access to the gallery was at the first floor level, some two metres above the ground, and must have been reached by wooden stairs or a ladder.

The interior space, which is about 10 metres in diameter, was partitioned by upright sandstone flags but, in this case, there the broch seems to have been a duplex with two distinct living quarters, each with its own hearth and double-decker compartments. The latter were probably used for storage but some of them, the larger ones at any rate, may well have been used as box-beds. There was a set of stairs to an upper storey in the smaller of the two rooms but it would appear that it, like the rest of the arrangements on the ground floor, was not part of the original design. This was confirmed when part of an earlier hearth was uncovered when some of the paving slabs of the floor were lifted in the central area.

At the same time as they discovered the earlier hearth, the excavators located the entrance to what appeared  to be a well (surrounded by the guardrails in the photo, below left). However, it turned out to be much more complex than it first appeared. Its construction entailed hacking a large cavity (4 metres deep and over 5 metres across) out of the bedrock—probably before they built the broch. Then they built a set of 18 drystone steps that led down to a corbelled chamber with a cistern at the bottom. Cells were built into the ceiling and into the stonework under the steps. This is all rather over elaborate for a well—a simple shaft with a rope and bucket would have served much better. Pits and shafts are a common feature of the Iron Age in many parts of Europe and probably has something to do with the deities of the earth and the underworld. In fact, a remarkably similar underground structure was found not far away at a site known as Mine Howe (far right). In this case, there are two flights of stairs, with a landing in between, leading down to what appears to be a cistern There are short galleries leading off the

to be a well (surrounded by the guardrails in the photo, below left). However, it turned out to be much more complex than it first appeared. Its construction entailed hacking a large cavity (4 metres deep and over 5 metres across) out of the bedrock—probably before they built the broch. Then they built a set of 18 drystone steps that led down to a corbelled chamber with a cistern at the bottom. Cells were built into the ceiling and into the stonework under the steps. This is all rather over elaborate for a well—a simple shaft with a rope and bucket would have served much better. Pits and shafts are a common feature of the Iron Age in many parts of Europe and probably has something to do with the deities of the earth and the underworld. In fact, a remarkably similar underground structure was found not far away at a site known as Mine Howe (far right). In this case, there are two flights of stairs, with a landing in between, leading down to what appears to be a cistern There are short galleries leading off the  landing and the whole thing was incorporated into a mound.

landing and the whole thing was incorporated into a mound.

Similar wells have been identified at nine other brochs and probably existed at many more but went unnoticed by early antiquariansThere was no well at Howe but there was an underground chamber—a Neolithic chambered tomb that had been converted into a souterrain. Souterrains (known as earth-houses in Scotland) were a feature of the Iron Age of Atlantic Europe and can be found as far south as Brittany. They are essentially underground galleries lined with stone slabs or timber. The earth-house at nearby Rennibister (right) is a good example. It was long thought that they were underground storerooms and that may well have been their primary function, but more recent opinion has favoured a ritual use as well. The fact that the bodies of a youth and a young woman had been placed in the souterrain at Howe would seem to support this idea.

Entrance to Gurness Broch

The entrance passage was five metres long originally and was blocked by a stout door set halfway along. There were doorjambs, a stone sill, a pivot stone and two bar holes on either side where a beam could be run out from one of the guard rooms on either side—although the evidence from Midhowe (see below) suggests we may be wrong in that interpretation. The entrance too was remodelled at some later point in the site’s history by the addition of a curved outer work, which seems to have served little practical purpose other than to lengthen the passage and perhaps make it more imposing.

Aerial View of Gurness

The northern part of the site has suffered from coastal erosion so we cannot be certain but it looks as if the entire site was originally surrounded by a roughly circular arrangement of concentric ramparts and ditches enclosing an area of about 1,000 square metres. The innermost rampart, which consists of a stone wall rising straight up from the floor of the inner ditch, was probably contemporary with buildings. The outer two ramparts are earlier, perhaps even pre-dating the broch. Rings of ditches and ramparts are not exactly uncommon in prehistoric Britain and they are not exclusively military in function. Henge monuments, such as the nearby circles at Stenness and Brodgar, are the most obvious examples, and were used to set the realm of the supernatural apart.

View of the Ramparts from the South

The village, of which 14 houses now survive, was built after the broch—although how long after is a matter of debate. Craw, the original excavator, assumed that they represented a secondary, squatter occupation on the site as the tower began to fall to ruin but the excavations at Howe show that they were probably contemporaneous. The surviving arrangement of walls and rooms is not entirely origina, however,l and the site was undoubtedly remodelled more than once during its history.

Main Entrance to the Site

The entrance is on the east side and a narrow corridor or passage runs through the surrounding houses, straight to the entrance to the broch itself where it divides to surround the base of the tower. As at Howe, access was controlled by gates. Houses ranged in size from 14-75 square metres and varied somewhat in layout—although they shared many of the same features. Most were subdivided into two or more ‘households,’ each with its own hearth and furnishings—double-decker compartments; tanks, ovens and privies. Unlike Howe, there were no open areas and, with the possible exception of the pathway, the whole settlement must have been roofed over. Assuming that the roofs were lightweight, thatched constructions, this would have meant a huge drainage problem given the local climate.

View towards the entrance to the broch from a house in the village

The cultural remains include some 850 artefacts, mainly of bone and stone, and a huge amount of pottery. There is evidence of metalworking but few objects have survived. Mould fragments show that bronze pins and knobbed spear-butts (similar to examples found in Ireland) were made here but presumably out of doors.