At least fifty brochs have been identified in Orkney but there were doubtless many others that have been robbed of their stone and are now all but invisible in the archaeological record. Unlike elsewhere in Scotland, where rugged individualism seems to have been the norm, there is clear evidence of a hierarchy of settlement in Orkney.

Broch Villages

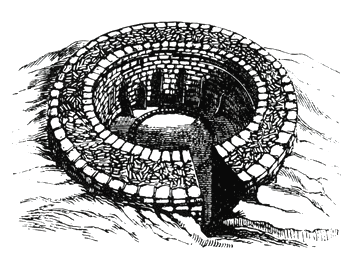

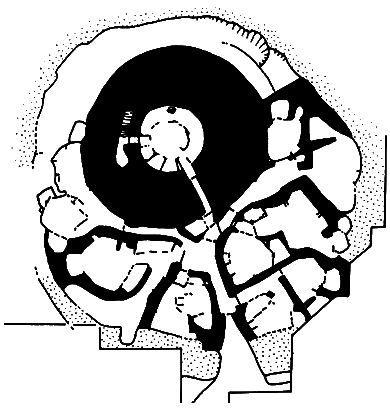

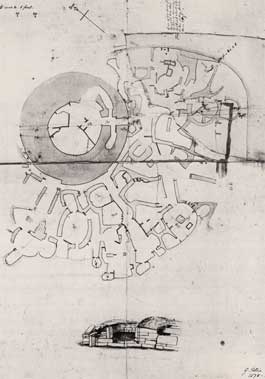

One distinctive feature of Orcadian brochs is the occurrence of outbuildings at a number of sites. Unfortunately, it was the general opinion in the nineteenth century that these clusters of small houses represented a later, squatter occupation after the broch had been destroyed or abandoned by the original builders. Their remains were generally swept aside and often not noted at all. Early antiquarians tended to be somewhat offhand in their methods and this is particularly true when it came to recording—often only a sketch plan survives. To the right is the plan of Lingro Broch on the outskirts of Kirkwall, excavated by George Petrie in the 1870s, which clearly shows the broch village. Now virtually obliterated, it would have been the largest such village in Orkney.

The only recorded excavations were those undertaken by John Hedges at Howe where he showed that the village was part of a major reconstruction of the site that also included the broch. At some time in the last century BC or first century AD the roundhouse settlement was levelled and a new one built in its place. At the heart of the new settlement was a massive broch with walls 5.5 metres thick (vs. 3.5 metres for its predecessor). Walls this thick, amounting to nearly two-thirds the diameter of the building, suggest a tall structure, about the same size as the broch at Mousa in Shetland. As stated above (The Roundhouse Tradition) the central area of the broch was largely cleared out later in the Iron Age but enough remains to indicate that interior was subdivided by upright slabs of sandstone and fitted with stone cupboards.

A new set of ramparts was built surrounding the broch and within these were six houses, neatly organized with three on each side of the entrance passage. Access was controlled by gates set along each branch of the narrow lane. Due to spatial constraints, the houses were of different shapes and  sizes but each of them contained a hearth, an oven and a stone-lined tank. Flagstone partitions were used to set off storage areas, cupboards or closets, from living space. One of them even had a small privy, equipped with what must be a commode. Each house also had some open space attached, with roofed storage space where fodder or tools might have been kept. We know that they kept domestic fowl and carbonized dung from a milk-fed calf was found in one of the yards but there was not enough space to keep larger animals such as cattle within the settlement, except in the case of dire emergency. There is little in the way of evidence of craft activity such as bone- or stone-working and these must have taken place outside the ramparts.

sizes but each of them contained a hearth, an oven and a stone-lined tank. Flagstone partitions were used to set off storage areas, cupboards or closets, from living space. One of them even had a small privy, equipped with what must be a commode. Each house also had some open space attached, with roofed storage space where fodder or tools might have been kept. We know that they kept domestic fowl and carbonized dung from a milk-fed calf was found in one of the yards but there was not enough space to keep larger animals such as cattle within the settlement, except in the case of dire emergency. There is little in the way of evidence of craft activity such as bone- or stone-working and these must have taken place outside the ramparts.

The houses and their attached yards must have each served the needs of a single nuclear family of perhaps six or seven individuals. Including the residents of the broch itself, that would suggest a population of something like forty to fifty people for the whole settlement. Each family apparently stored and cooked their food separately—somewhat unusual, given the close proximity in which they all lived. The buildings suggest a hierarchical arrangement with the dominant family living in the broch tower with other families of lower but similar status occupying the surrounding houses—perhaps a chief and his closest relatives or retainers. Of course, this interpretation is based on models from later Scottish history. It is equally plausible that the broch tower was a communal building, used as a meeting place and/or a feasting hall—interpretations that also have parallels in later times.