The West Court

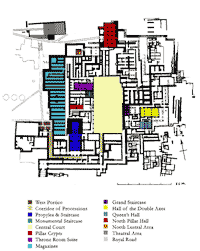

The West Court was clearly an important feature of the palace—as it was at the other major palaces at Phaistos and Mallia (although not at Kato Zakro). It was paved with large, irregular slabs of limestone and was crossed by a number of raised walkways or causeways. The area was much disturbed by later activity, so it is impossible to be precise, but, in the Second Palace Period at least, it appears to have run alongside the  palace from the West Porch to the North-West Treasure House, a distance of about 45 metres. The pavement can be traced about 30-35 metres to the west of the palace (depending on which datum points are used) but undoubtedly extended somewhat further, to the line of the enceinte wall (see below).

palace from the West Porch to the North-West Treasure House, a distance of about 45 metres. The pavement can be traced about 30-35 metres to the west of the palace (depending on which datum points are used) but undoubtedly extended somewhat further, to the line of the enceinte wall (see below).

The North-West Treasure House dates to the beginning of the Second Palace Period and was clearly a building of some importance to be included within the palace precinct. Unfortunately, only the basement rooms have survived but these were found to contain quite a number of high status items—finely crafted polychrome pottery, jewellery and a rich trove of bronze vessels. Evans concluded, no doubt rightly, that it belonged to some important shrine within the palace itself. In the time of the first palace, therefore, the court probably extended much further north, perhaps as far as the later Theatral Area.

A paved causeway 1.40 metres wide (the same as the Royal Road) ran from the north, along the palace façade and directly to one of the main entrances, the West Porch. There is no direct link but presumably it originated as the ramp that bisected the southern tier of steps in the Theatral Area. At a point about 20 metres beyond the treasury, it splits in two with one branch carrying on to the  West porch and the other heading off at a 60° angle to the southwest.

West porch and the other heading off at a 60° angle to the southwest.

The latter ran past a row of three circular, stone-lined pits about 5-6 metres in diameter and 3 metres deep. Evans called them koulourai (after a traditional type of Greek bread ring). Upon excavation, they proved to be full of broken pottery and other typical items of domestic rubbish from the First Palace Period. But just because they were ultimately used as dump sites does not mean that that was their original function. Until recently, the consensus of opinion had been that they were granaries similar to the above ground examples found at the palace of Mallia—despite the fact that they never had floors and that no trace of a roof has survived. Evans offered the suggestion that they may have been what he calls “blind wells,” used to quickly drain away surface water.

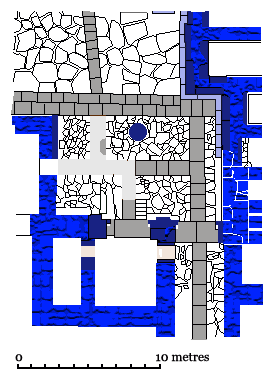

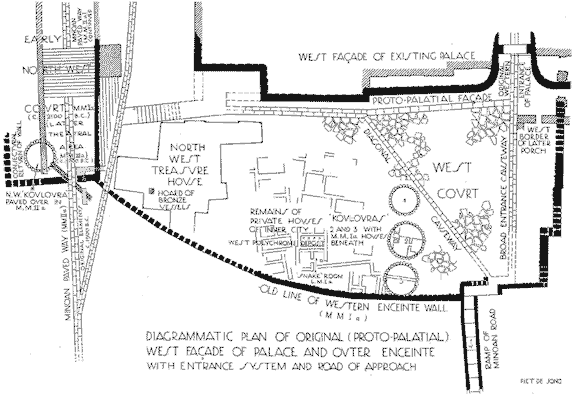

Another causeway ran along the southern edge of the court from the west. Just before the point where it would have intersected with the diagonal causeway, Evans discovered the remains of a massive wall associated with the construction of the First Palace. He called it the Enceinte, a French term that was originally applied to the inner ring of fortifications surrounding a town or castle. Although disturbed by later houses, much of its line can be traced (see the plan below). He included the area of the earlier version of the North-west Court that underlay the Theatral Area on the basis of its stratigraphic level although it was impossible to establish a direct architectural link.

Plan of the West Court. First Palace Period (Evans PM 4, Fig 30).

A stepped ramp led up to the court from the west and intersects with it just to the north of the two causeways. It then makes a slight dog leg to the south, screened by a short stretch of wall, before it actually enters the court. At the base of the enceinte, in the angle between it and the ramp, Evans found the remains of a small, walled enclosure that he took to be a guard room. Evans believed that what he called the ‘Broad Entrance Causeway’ ran directly to the entrance to the First Palace but the evidence for such an entrance, based on what he took to be a rounded corner on the stretch of the earlier wall, has been discounted.

Altar in the West Court

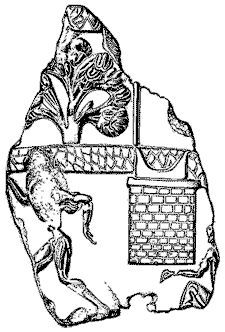

The western façade is made up of a number of staggered blocks of storage magazines supporting at least one upper storey. Each block had a broad, shallow niche facing the court and, in front of two of them, Evans found bases for altars. He was immediately reminded of a fragment from a steatite vase from the site that he had acquired a few years before he began excavations (opposite). It depicts such an altar made of ashlar masonry and topped by a set of sacral horns. The setting is outdoors in what appears to be an open area. In the background is a fig tree set behind a wall of somewhat rougher masonry while in the foreground there are two sinewy looking male figures who appear to taking part in ritual activities.

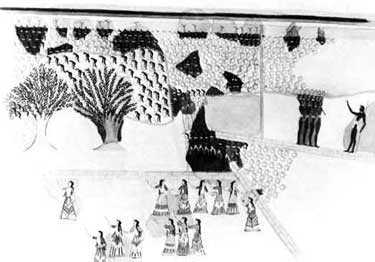

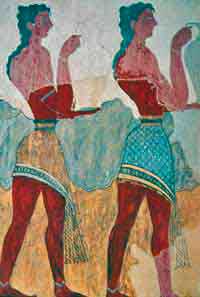

James W. Graham believes that the niches were decorative surrounds for large windows in the upper storey, comparable to the ‘windows of appearance’ in contemporary Egyptian palaces and temples. He imagined the elite of the palace standing at these windows to witness the rites and ceremonies taking place in the courtyard below. The Sacred Grove Fresco, which Evans found in a small shrine in the palace, gives a clue as to what these ceremonies may have been. The reconstruction (opposite) shows a very similar looking paved area with what appear to be the same sort of raised walkways, shown as viewed from above in the Egyptian fashion. Crowds of people (only their heads are shown) have gathered around a  grove of olive trees. Groups of young men, distinctively clad in necklaces and short kilts, stand information along the walkways, while in the foreground, separate from the others, groups of young women, who were undoubtedly priestesses, appear to be gesturing towards each other and to something happening out of frame.

grove of olive trees. Groups of young men, distinctively clad in necklaces and short kilts, stand information along the walkways, while in the foreground, separate from the others, groups of young women, who were undoubtedly priestesses, appear to be gesturing towards each other and to something happening out of frame.

Similar scenes on signet rings, such as the one from Isopata(left) suggest that the celebrants are witnessing the epiphany of a deity. There is no evidence that there were any olive trees in the West Court but realism was never a huge concern to ancient artists. Certainly, the trees suggest an agricultural festival—most likely a harvest festival, if the presence of all those storage rooms just behind the western façade is any indication. In most cultures, the West is the land of the dead. It is not difficult to see the connection—the sun, the source of all life, disappears in that direction every day. The harvest involves the taking of life, as does the slaughter of the animals which takes place at the same time.

West Porch

The two main causeways each led to the West Porch in the south-eastern corner of the courtyard. The layout is fairly simple—an open portico with a single column sits in front of a pair of identical doorways (they have the same width, 2.95 metres, at any rate). But Evans was struck by the fact that the eastern end of the porch was rather awkwardly tucked behind a jog in the palace façade. This was certainly not the original arrangement because Evans found that the pavement of the east-west causeway had been cut back slightly during the Second Palace Period to  accommodate the plinth of the wall.

accommodate the plinth of the wall.

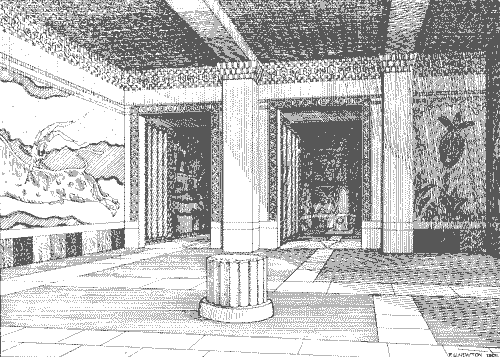

The final construction was a fairly simple affair, although there is barely a square corner in the entire suite. A single massive column supported supported the roof of a broad portico. Its stone base was 1.20 metres in diameter which, assuming a ratio of height to base of 5:1, suggests that the wooden column may have been as much as six metres tall. The walls were decorated with painted plaster—figurative compositions above a dado of imitation marble.

Two walkways led to the doorways at the rear of the portico. The one on the left looking into the porch was the start of a long narrow passage leading to the interior of the palace. To make it absolutely clear that this was the way to go, there was an enormous mural of a bull on the adjacent wall. Only a few bits of painted stucco (part of one of his forelegs and a patch of his back) still adhered to the wall when Evans uncovered it but it was almost certainly a scene that showed a youthful toreador vaulting over the back of the animal.

Reconstruction of the West Porch drawn by F. G. Newton

The portal to the right led to a small suite of two rooms that Evans thought was laid out to receive visitors to the palace. The principal room measured 4.60 x 4.25 metres and had a doorway to the east that linked it to the corridor. Evans believed that the room had originally contained a throne on which the priest-king of Knossos sat and displayed himself to to the crowds assembled in the courtyard. Adjoining it was a narrower room which Evans described as a Porter’s Lodge but might equally have been a robing room or a place for the king to retire from view for whatever reason. Leaving aside opinions as to whom the occupant might be, it all sounds highly plausible but not the faintest trace of a throne has survived.

The Corridor of Procession

Like the porch, the passageway leading from it replaced an earlier version at a slightly lower level. At 3.34 metres, it was also about a metre wider. The raised pavement of the walkway continues from the porch into the corridor—for the first few metres, at any rate. The paving slabs were of gypsum and, as was the case in the West Porch, were coated with a thick layer of hard plaster. The  green schist slabs flanking them, on the other hand, were coated with dark red.

green schist slabs flanking them, on the other hand, were coated with dark red.

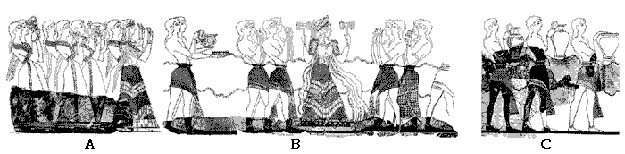

The corridor takes its name from the theme of the murals on its plastered walls that show files of figures heading along it. Most of what has survived consists of fragments of stucco, three to five centimetres thick, found in the fill of the underlying level, but a good deal was found still adhering to the walls, especially on the left-hand side as you entered. Evans believed (based on the scale and number of fragments he found) that there were over 500 figures arranged, for the most part, in two registers.

Very little has survived of the right-hand (west) wall but those opposite are preserved to a certain extent for the first 9 metres and depict pairs of figures starting immediately inside the door with a group (A) that have been reconstructed as number of young men in long robes, playing musical instruments. They are led by a pair of priestesses with their hands raised in a gesture of adoration. Further along is another scene with a goddess figure flanked by adoring young men. The next grouping is better preserved (above left) and shows a number of kilted youths bearing vessels, presumably filled with oil or wine (my money would be on the latter). The details are somewhat imaginative (since nothing survived above the ankles) but not baseless. Evans’ found parallels in other pieces of Minoan art, such as the painted scene on a terracotta sarcophagus from Aghia Triadha.

Reconstruction of the Cupbearers Fresco in the Corridor of Procession

Although the floor disappears, owing to the slope of the hill, after 17 metres but Evans was able to trace its line on the basis of the foundations of the underlying rooms and the abundant fragments of painted plaster. It continued for another 7 metres and then made a 90° turn to the left (east) and ran for another 48 metres before turning north, to the Central Court.

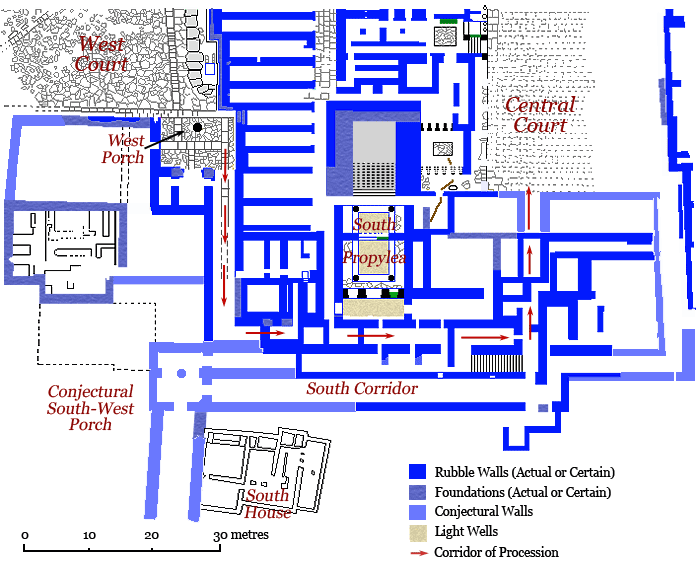

Plan of the southern part of the Palace (after Evans)

At a point about a third of the way along the east-west stretch of corridor the evidence for painted murals ceases. It is here that Evans has reconstructed his South Propylaeum, a massive doorway structure, and a monumental staircase leading to the upper storey (see The Piano Nobile). Murals with essentially the same theme were found on its walls as well but, in this case, the figures were heading out to meet those in the corridor.

Although the floor of the corridor had disappeared, Evans found the same sort of green schist slabs in the basement rooms below, along with a small bit of ledge at the appropriate level on the far side of the Propylaeum. However, it must be borne in mind that Evans was very keen to prove his contention that there ‘ought’ to be a direct connection between the West Court and Central Court.

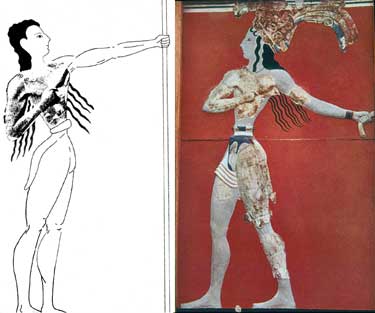

It was in one of the basement rooms underneath the last stretch of corridor that Evans found the fragments of the so-called Prince of the Lilies. He felt certain that it must have marked the end of the entrance to the court but current thinking is that Evans’ restoration was wrong and the pieces belonged to more than one figure (below).

The headdress on the right-hand figure is more appropriate to a goddess or one of her attendant sphinxes. The clenched fist with the other arm extended to hold a staff is a fairly common posture for the young god, as shown in the left-hand reconstruction. The legs most likely belong to another figure entirely.

Unless otherwise stated, all black & white photos of Knossos are from The Palace of Minos by Arthur Evans and are reproduced here courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University