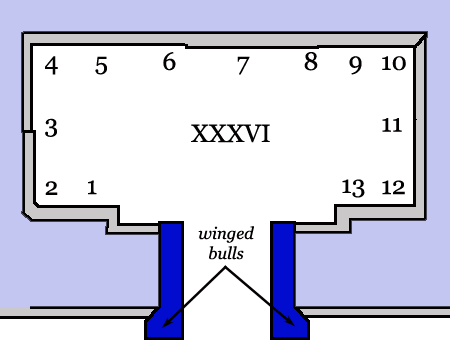

Slabs 1 & 2

Location of Reliefs in Room XXXVI

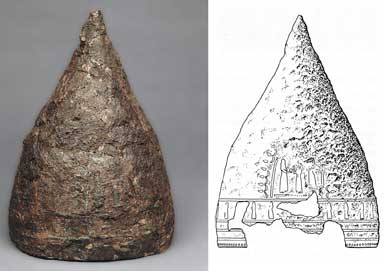

The first set of reliefs, on the left hand wall as you entered the door, depict two lines of prisoners, probably taken from Lachish itself, being driven along by unsympathetic men brandishing sticks.  They are met by two files of Assyrian spearmen (below right) wearing pointed, conical iron helmets and carrying spears and large, round, slightly conical shields. When the hand grip is visible, it is in the centre. The Greek shields of a slightly later period had the hand grip towards the rim of the shield and a strap for forearm at the centre. This made the grip more secure and allowed the soldier to carry a heavier shield. Although metal examples have been found, these were probably ‘parade’ versions only.

They are met by two files of Assyrian spearmen (below right) wearing pointed, conical iron helmets and carrying spears and large, round, slightly conical shields. When the hand grip is visible, it is in the centre. The Greek shields of a slightly later period had the hand grip towards the rim of the shield and a strap for forearm at the centre. This made the grip more secure and allowed the soldier to carry a heavier shield. Although metal examples have been found, these were probably ‘parade’ versions only.

Assyrian soldiers had different arms and equipment according to their role on the battlefield and the part of the empire from which they came. In this case, the soldiers appear to be from the home provinces, local militiamen from northern Iraq. The helmet was made out of iron, normally hammered out of a single sheet, and had flaps to  protect the ears. Normally, Assyrian spearmen wore scale armour but in this case they appear to be dressed in knee-length tunics of linen or wool. On their feet they wore leather boots that laced up the front as high as their knees.

protect the ears. Normally, Assyrian spearmen wore scale armour but in this case they appear to be dressed in knee-length tunics of linen or wool. On their feet they wore leather boots that laced up the front as high as their knees.

Despite their small size, spears were not meant to be thrown but were used for thrusting in close formation fighting. They were the principal offensive weapon for most of the army. These men wore a short iron sword or dirk at their waists but these were probably only used in a melee or to dispatch the wounded.

The prisoners (left), including women and children, have their hands raised as supplicants and are pleading for mercy. The men have close-cropped curly hair and beards. Each of them wears a simple knee-length tunic, belted at the waist, with a fleece draped over their shoulders. Some of them have their wrists bound. The women have slightly longer and straighter hair, and wear much the same tunics but unbelted, and each has a cloak of some sort on top of that. Some of the women have sacks slung over their shoulder while others lead small children by the  hand. Assyrian artists were quite attentive to detail since they were required to show the diversity of the empire and to offer easily recognized stereotypes for the viewer.

hand. Assyrian artists were quite attentive to detail since they were required to show the diversity of the empire and to offer easily recognized stereotypes for the viewer.

It is abundantly clear that that they are in need of mercy, because the top register includes a scene showing soldiers piling up severed heads in front of two military scribes (left) who record the number and the name of the soldier for the payment of bounty. By this time, one of the scribes was inscribing the official version in cuneiform characters with a reed stylus onto a clay tablet while the other was writing essentially the same thing down (in Aramaic, the language of everyday business within the empire) with a brush on a parchment scroll.

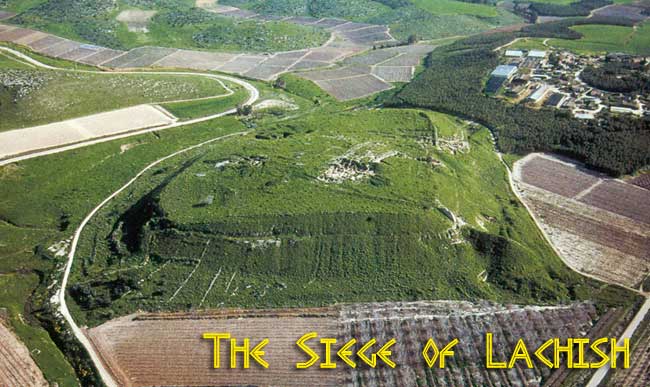

We know that the scene takes place somewhere in the Levant because, below the pedestrian figures, is a line of Assyrian cavalryman (opposite right) standing by their mounts in the midst of a hilly landscape (represented stylistically by what appear to be small sugar loaves) interspersed with vines. This is the conventional way of depicting the lands that lay along the eastern end of the Mediterranean.