Early Explorations

Youth

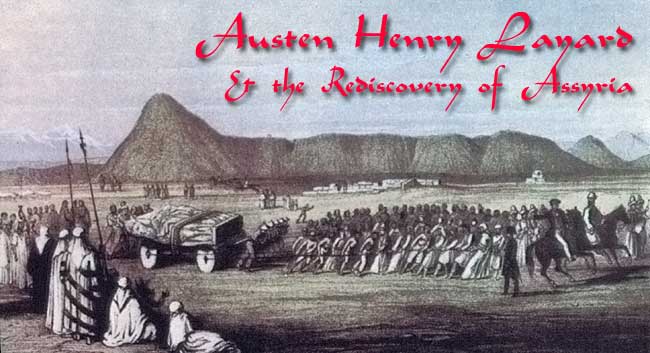

Austen Henry Layard was one of the great archaeological pioneers of the Victorian Age. Together with Paul Emile Botta, he brought to light one of the major civilizations of the ancient world, that of Assyria.

Of course, in a profoundly religious age, most Europeans were quite familiar with the Assyrians from the Old Testament, where they appear as brutal conquerors who dragged  the ten lost tribes of Israel into captivity. Virtually nothing else was known of the Assyrians themselves until Botta and Layard uncovered the remains of their palaces in the plains of northern Iraq.

the ten lost tribes of Israel into captivity. Virtually nothing else was known of the Assyrians themselves until Botta and Layard uncovered the remains of their palaces in the plains of northern Iraq.

Fortunately for us, Layard was a prolific writer and we know a good deal about his life and career. Literally thousands of his letters along with extensive diaries and notebooks can be found in the Library of the British Museum. He published several volumes on his work and experiences in the Near East and an autobiographical work entitled Early Adventures.

Henry was born in a hotel on the Left Bank in Paris on March 5th, 1817. His father, Peter Layard, suffered from asthma and, although from a respectable family, was not a particularly wealthy man. It was much cheaper for he and his wife Marianne to live on the Continent, and the climate was better for his health. Layard spent much of his youth in France and Italy and enjoyed himself thoroughly—although he received little in the way of formal education. His parents encouraged his interest in art and literature, however, and, when the family eventually moved back to England, he was sent off to public school. He hated the whole experience and did not get along at all with his fellow students who resented his Continental airs.

Henry’s father died shortly after their return and had to rely on his mother's brother, a fairly well to do lawyer named Benjamin Austen. To please his uncle, he changed the order of his names from Henry Austen to Austen Henry and, after he finished school at the age of 17, took up an apprenticeship in his law firm, with a view to eventual partnership. But he found the office routine a complete bore and lived only for the weekends and holidays. On Sundays, he was often invited to his uncle's house where he met many of the most important people of the time—including young Benjamin Disraeli. He also met Charles Fellows, a noted ‘gentleman traveller’, who some years earlier had travelled throughout south-western Anatolia (modern Turkey), exploring the ruins of ancient Lycia (his drawing of the ruins at Aphrodias is shown right). He was very helpful to Layard when it came time for him to begin his own explorations of the region-which routes to follow and which areas had archaeological potential. That same summer, he went on an extended trip to Scandinavia and St. Petersburg and, while in Copenhagen, met Christian Thomsen, founder of the Danish National Museum. Thomsen was the man who devised the Three Age System of classification for archaeological material-the Stone Age; Bronze Age; and Iron Age-and he gave Layard a personal tour of the collection.

for the weekends and holidays. On Sundays, he was often invited to his uncle's house where he met many of the most important people of the time—including young Benjamin Disraeli. He also met Charles Fellows, a noted ‘gentleman traveller’, who some years earlier had travelled throughout south-western Anatolia (modern Turkey), exploring the ruins of ancient Lycia (his drawing of the ruins at Aphrodias is shown right). He was very helpful to Layard when it came time for him to begin his own explorations of the region-which routes to follow and which areas had archaeological potential. That same summer, he went on an extended trip to Scandinavia and St. Petersburg and, while in Copenhagen, met Christian Thomsen, founder of the Danish National Museum. Thomsen was the man who devised the Three Age System of classification for archaeological material-the Stone Age; Bronze Age; and Iron Age-and he gave Layard a personal tour of the collection.

He finished his apprenticeship and wrote his final examinations in 1839 but had decided by then that the law as a career held no attraction for him-at least not in London. An alternative presented itself to him in the form of another uncle who had just returned from Ceylon and suggested that Layard pursue his legal career there. He leapt at the chance. He was lucky enough to be introduced to another young man, Edward Mitford, who was also planning to go to Ceylon (to start a coffee plantation) and the two of them decided to travel together—overland and on horseback! It was a risky plan, particularly since Persia, through which they had to pass, had just recently broken off diplomatic ties with Britain—but they were determined nevertheless. To prepare himself, Layard talked to members of the Royal Geographic Society and read everything he could get a hold of on the countries involved, including a pamphlet by a certain Major Rawlinson.

The Journey East

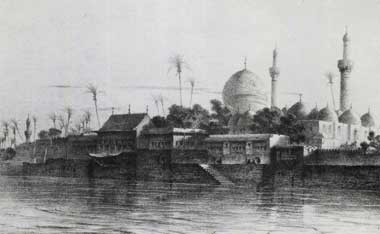

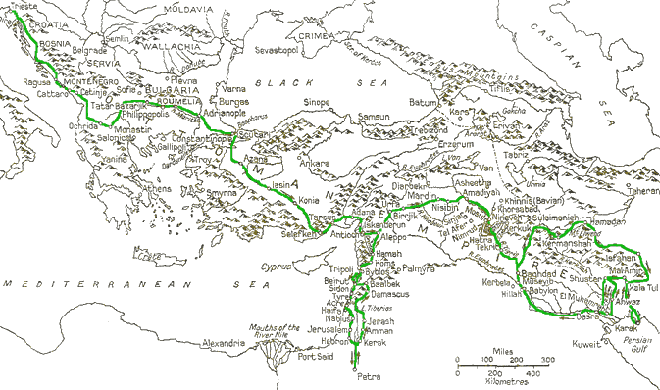

Layard left London on July 10th 1839, taking the steamer to Ostende and meeting up with Mitford in Brussels. As funds were short, they intended to travel light but well armed—they each bought a double-barrelled rifle and Layard bought a pair of pistols as well. Since the planned  to make detailed surveys en route (Layard had taken courses before he left London) they also purchased a sextant and compasses. He had deposited £300 with a bank in order to be able to draw on funds while he was travelling and the pair of them had received £200 from a publisher as an advance on a proposed account of their travels. They headed for Montenegro, whose mountain strongholds had never been subdued by the Turks and was the only Christian-ruled country in the Balkans, and continued through Albania and Macedonia, reaching Istanbul (left) by the middle of June. Layard had come down with malaria on the way and was bedridden for several weeks after arriving-enduring a treatment which included blood-letting with leeches. They crossed the Hellespont at the beginning of October and headed overland through Anatolia-noting the ancient monuments and ruined sites which they passed along the way. When they reached Syria, they found the region devastated by the armies of the Egyptian pasha, Mohammed Ali, who had recently annexed all of the Levant. The people had to suffer the burden of harsh taxation by the Egyptian government and the affects of a complete breakdown of law and order—the Egyptian soldiers had not been paid in two years.

to make detailed surveys en route (Layard had taken courses before he left London) they also purchased a sextant and compasses. He had deposited £300 with a bank in order to be able to draw on funds while he was travelling and the pair of them had received £200 from a publisher as an advance on a proposed account of their travels. They headed for Montenegro, whose mountain strongholds had never been subdued by the Turks and was the only Christian-ruled country in the Balkans, and continued through Albania and Macedonia, reaching Istanbul (left) by the middle of June. Layard had come down with malaria on the way and was bedridden for several weeks after arriving-enduring a treatment which included blood-letting with leeches. They crossed the Hellespont at the beginning of October and headed overland through Anatolia-noting the ancient monuments and ruined sites which they passed along the way. When they reached Syria, they found the region devastated by the armies of the Egyptian pasha, Mohammed Ali, who had recently annexed all of the Levant. The people had to suffer the burden of harsh taxation by the Egyptian government and the affects of a complete breakdown of law and order—the Egyptian soldiers had not been paid in two years.

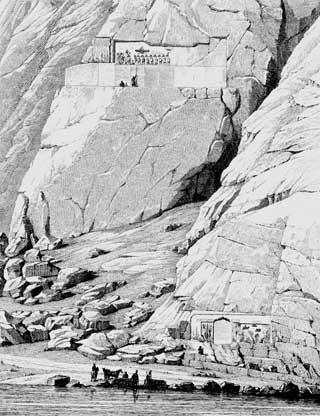

They reached Jerusalem in February 1846 and, while there, Layard heard of the spectacular ruins at Petra (opposite right), south of the city, and expressed a desire to visit them-despite the fact that the area was beyond government control. Mitford refused to go along and they agreed to split up for the time being and meet again in Aleppo. Layard made arrangements with one of the local sheikhs to provide protection and a couple of guides (at a price)—any attack on Layard would therefore involve the offender in a blood feud with the tribe. That was how it was supposed to work in theory, at least, but things do not always go according to plan. His party was attacked by robbers almost at once and they escaped only because Layard rode straight up to the leader and levelled one of his pistols at the man’s head. When they reached Petra the local tribe demanded a  huge sum for permission to view the ruins and when Layard refused to pay, things got ugly. On the way back, he was continually harassed, deserted by his guides and robbed several times—the last time by a group of Egyptian army deserters.

huge sum for permission to view the ruins and when Layard refused to pay, things got ugly. On the way back, he was continually harassed, deserted by his guides and robbed several times—the last time by a group of Egyptian army deserters.

He finally reached Damascus (left) clad only in trousers and the shirt on his back, with but a single coin, which had been overlooked by the robbers, at the bottom of his saddlebag. Fortunately, that was enough of a bribe to enable him to avoid the forty day quarantine imposed because of the plague that was ravaging the district. He finally met up with Mitford at Aleppo and the started out on the trek east to Mosul in the middle of March, 1840.

Map Showing Layard's Travels 1839-1841

Mesopotamia

Layard and Mitford spent more than two weeks in Mosul and were particularly impressed by the ruins across the river—especially Layard who insisted on visiting them all. As he later wrote:

These huge mounds of Assyria made a deeper impression on me, gave rise to more serious thoughts and more earnest reflection than the temples of Balbec, and the theatres of Ionia….

A deep mystery hangs over Assyria, Babylonia and Chaldaea…. With these names are linked great nations and great cities dimly shadowed forth in history; mighty ruins in the midst of deserts, defying, by their very desolation and lack of definite form, the description of the traveller; the remnants of the mighty races still roving over the land; the fulfilling and fulfilment of prophecies; the plains to which the Jew and the Gentile alike look as the cradle of their race.

(Layard 1849, vol. I: 2-3)

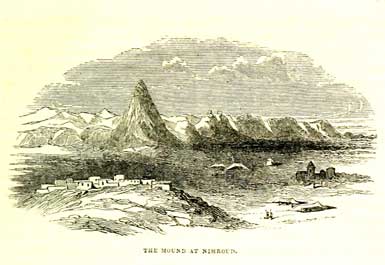

While in Mosul they met the French explorer, Charles Texier, who was on his way back home after exploring the ruins of Persia where he made a number of drawings and plans of Persepolis and Pasargadae. The English Vice-Consul, a local Christian named Christian Rassam, invited the pair on a trip to the ruins of Hatra where a number of buildings of the Persian and Hellenistic periods were wonderfully preserved. As it happened, their first campsite was across the river from the ruins of Nimrud, a place where Layard was destined to spend a lot of time:

As the sun went down, I saw for the first time the great conical mound of Nimrud rising against the clear evening sky. It was on the opposite side of the river and not very distant, and the impression that it made upon me was one never to he forgotten. After my visit to Küyünjik and Nebi Yunus, opposite Mosul, and the distant view of Nimrud, my thought ran constantly upon the possibility of thoroughly exploring with the spade those great ruins.

(Layard 1903: 311)

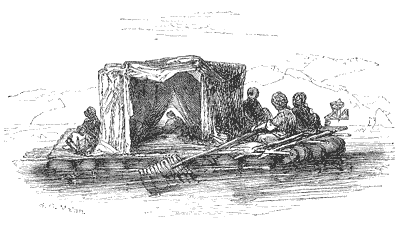

Eventually, the pair decided they must be on their way and rented a kelek (a raft of inflated goat skins) to take them south to Baghdad. At Nimrud, they  encountered rapids which the skipper explained were caused by the remains of a large dam built by King Nimrod. Within a week they were in Baghdad and were received by the current British Resident, Colonel Taylor. They stayed for a couple of months, visiting some of the more important ruins in the neighbourhood— especially the remains of ancient Babylon—and taking advantage of the resources of Taylor’s library.

encountered rapids which the skipper explained were caused by the remains of a large dam built by King Nimrod. Within a week they were in Baghdad and were received by the current British Resident, Colonel Taylor. They stayed for a couple of months, visiting some of the more important ruins in the neighbourhood— especially the remains of ancient Babylon—and taking advantage of the resources of Taylor’s library.

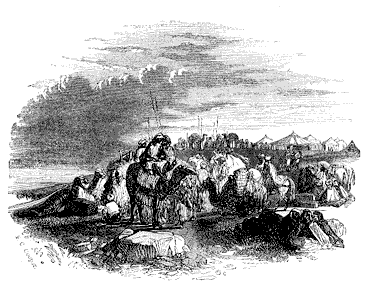

They intended to continue overland, through Persia to India—despite the fact that war was looming between the Shah and the Sultan and that, as already mention, relations were strained between Persia and Britain. They decided to cross the Zagros mountains by way of Kermanshah and, donning local dress in order to blend in as much as possible, joined up with a small caravan composed mainly of poor Shi’ite  pilgrims, returning from the holy places in southern Iraq. When they arrived at Kermanshah, they went to visit Bisitun (left) where the cliffside bore a lengthy trilingual inscription and while they were there ran into a Frenchman named Flandin who was drawing the monument. At this point they learned that, if they wished to travel further through the Shah's dominions, they would have to seek official approval from the latter or his vizier at Hamadan.

pilgrims, returning from the holy places in southern Iraq. When they arrived at Kermanshah, they went to visit Bisitun (left) where the cliffside bore a lengthy trilingual inscription and while they were there ran into a Frenchman named Flandin who was drawing the monument. At this point they learned that, if they wished to travel further through the Shah's dominions, they would have to seek official approval from the latter or his vizier at Hamadan.

Layard had decided to take the southern route, through Seistan—in part because it was the region where Zoroastrianism was presumed to have originated but also because of the many ruins to be found there. The vizier refused to permit this—he regarded the pair of them as spies intent on gathering information about the routes between India and Persia. Layard was persistent, however, and proposed to proceed entirely at his own risk, without official permission or with any guarantees of their safety. Mitford, probably rightly, thought that this would be tantamount to signing their own death warrants and the two of them decided to split up. He took advantage of the vizier’s offer to provide official sanction for the more northern route to India by way of Afghanistan but Layard insisted on remaining in the vicinity in the hopes that the next year would bring a change in attitude and that he would be allowed to proceed as he desired. Although he maintained the pretence in his letters home, it is clear that by now Layard had lost interest in a career as a lawyer in Ceylon. However, he had no firm idea of what he wanted to do instead.

Among the Bakhtiaris

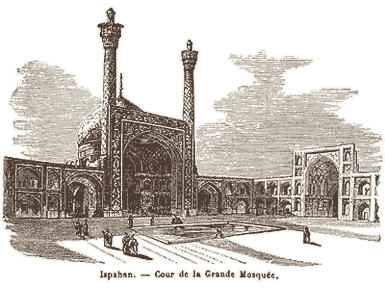

After Mitford had departed, Layard rode off into the mountains of Luristan and Khuzistan, dressed in the local garb (he is shown below, in Bakhtiari costume). However, the hostility of the local people coupled with recurrences of malaria forced him to turn back. So he went instead to Isfahan where he met with the Persian governor, a notoriously brutal Georgian eunuch named Manuchar Khan—his cruelty was excessive even by Persian standards. Shortly before Layard arrived he had ordered the construction of a tower out of 300 prisoners held together by mortar, which stood for weeks, long after the prisoners had died an agonizing death. In another case, he had a prisoner’s teeth extracted in order to be used as buckshot for his own execution.

The governor refused permission for Layard to travel through Seistan but did allow him to pass through the country of the Bakhtiaris to the south of Isfahan. Everyone warned him that it was a risky undertaking, that the Bakhtiaris were cruel and untrustworthy, but Layard was undaunted. After crossing their territory, he planned to continue south, to try and determine the location of ancient Susa (where the Book of Esther was set) and then travel on to Persepolis in the province of Fars. He set out in September of 1840, travelling with a caravan to Kala Tul, one of the mountain strongholds of the Bakhtiaris, but found that the chief, a man named Mehemet Taki Khan, was away.

The governor refused permission for Layard to travel through Seistan but did allow him to pass through the country of the Bakhtiaris to the south of Isfahan. Everyone warned him that it was a risky undertaking, that the Bakhtiaris were cruel and untrustworthy, but Layard was undaunted. After crossing their territory, he planned to continue south, to try and determine the location of ancient Susa (where the Book of Esther was set) and then travel on to Persepolis in the province of Fars. He set out in September of 1840, travelling with a caravan to Kala Tul, one of the mountain strongholds of the Bakhtiaris, but found that the chief, a man named Mehemet Taki Khan, was away.

While he was awaiting his arrival, Layard found that the eldest son of the Khan was very ill and, the local doctors having proved ineffectual, Layard was asked by the boy's mother and chief wife of the Khan, to intervene. Layard, who was always highly appreciative of beautiful women, was completely captivated by her and describes her in the most glowing terms. However, the two holy men who had been treating the boy absolutely forbade him to so much as touch the boy and sent instead for his father, who came galloping into the town at the head of his men. Layard was most impressed by him:

Mehemet Taki Khan was a man of about fifty years of age, of middle height, somewhat corpulent, and of a very commanding presence. His otherwise handsome countenance was disfigured by a wound received in war from an iron mace, which had broken the bridge of his nose. He had a sympathetic, pleasing voice, a most winning smile, and a merry laugh.

He was in the dress which the Bakhtiari chiefs usually wore on a journey, or when on a raid or warlike expedition—a tight-fitting cloth tunic reaching to about the knees, over a long silk robe, the skirts of which were thrust into capacious trousers, fastened round the ankles by broad embroidered bands. Round his Lur skullcap of felt was twisted the lung, or striped shawl. His arms consisted of a gun, with a barrel of the rarest Damascene work, and a stock—beautifully inlaid with ivory and gold; a curved sword, or scimitar, of the finest Khorassan steel—its handle and sheath of silver and gold; a jewelled dagger of great price, and a long, highly ornamented pistol thrust in the kesh-kemer, or belt, round his waist, to which were hung his powder-flasks, leather pouches for holding bullets, and various objects used for priming and loading his gun, all of the—choicest description. The head and neck of his beautiful Arab mare were adorned with tassels of red silk and silver knobs. His saddle was also richly decorated, and under the girths was passed, on one side, a second sword, and on the other an iron inlaid mace, such as Persian horsemen use in battle. Mehemet Taki Khan was justly proud of his arms, which were renowned throughout Khuzistan. He had a very noble air, and was the very beau-idéal of a great feudal chief.

Layard was immediately called upon to treat the son—his father offering the most extravagant rewards for a cure (failure would have undoubtedly meant his life). In the event, a dose of Dover’s Powder—an opiate that induces sweating—followed by some quinine proved efficacious and the boy recovered.

His success brought him the friendship of the Khan and his wife, Khatun-jan (“The Lady of my soul”), asked him to stay as a member of the family. She had a younger sister who was even more beautiful and the Khan suggested on more than one occasion that Layard convert to Islam and marry her, “the inducement was great but the temptation was resisted.” He spent the next few months hunting, training and touring the land under the Khan's protection—although, this did not prevent him being threatened and robbed on several occasions.

In the spring of 1841 the Persian governor received orders to subdue the independent Bakhtiari chief, who was beginning to think in terms of a separate state for his people, and demanded a huge tax from Mehemet Taki Khan, knowing that it would be impossible to collect. The Khan stalled for time and sent Layard to the Gulf island of Karak where a British garrison was stationed, hoping to get their support—Britain had broken off ties with Persia, it will be remembered. It took he and his guide several days to reach the coast and when they got there, all they could scrounge up was a leaky rowboat—a storm blew up and what was normally an overnight journey took a couple of days. In the end, the effort was futile—the British had absolutely no intention of getting involved in the tribal politics of the highlands—and Layard decided to return to Kala Tul with the bad news. His guide, assuming that Layard would remain with his countrymen, had meanwhile taken off with his horse leaving Layard to borrow a donkey and make his way back alone.

In the meantime, the governor had sent an army into the mountains to confront the Bakhtiari chief directly and Mehemet Taki Khan was forced to submit. He pledged his eldest son as a hostage in exchange for a fair hearing but the governor had no intention of  honouring his side of the bargain and he was forced to flee to the Mesopotamian plain with the rest of his family. The Persian army was unable to penetrate the marshes and the governor offered to give him free passage and restore him to office and, despite the protests of his kinsmen, the Khan agreed to trust him once again. He entered the Persian camp with some of his followers (including Layard) and was promptly thrown in chains. Layard, who had hung back and had not been noticed, managed to escape in a small boat and found his way back to the others in the Marshes. The Persians then demanded that the Arabs surrender the entire family and followers of Mehemet Taki—something that Arab honour and sense of hospitality would not allow. They unanimously decided to mount a rescue operation, a night attack on the Persian camp, in which Layard was an enthusiastic participant:

honouring his side of the bargain and he was forced to flee to the Mesopotamian plain with the rest of his family. The Persian army was unable to penetrate the marshes and the governor offered to give him free passage and restore him to office and, despite the protests of his kinsmen, the Khan agreed to trust him once again. He entered the Persian camp with some of his followers (including Layard) and was promptly thrown in chains. Layard, who had hung back and had not been noticed, managed to escape in a small boat and found his way back to the others in the Marshes. The Persians then demanded that the Arabs surrender the entire family and followers of Mehemet Taki—something that Arab honour and sense of hospitality would not allow. They unanimously decided to mount a rescue operation, a night attack on the Persian camp, in which Layard was an enthusiastic participant:

The camp of an Eastern army has rarely any proper outposts, and we were almost in the midst of the Persian tents before our approach was perceived. A scene of indescribable tumult and confusion ensued. The matchlock-men kept up a continuous but random fire in the dark. The Arabs who were not armed with guns were cutting down with their swords indiscriminately all whom they met. Bakhtiari and Arab horsemen dashed into the encampment yelling their war-cries. The horses of the Persians, alarmed by the firing and the shouts, broke from their tethers and galloped wildly about, adding to the general disorder. I kept close to Au Baba Khan, who made his way to the park of artillery, near which, he had learnt, were the tents in which his brothers were confined. I was so near the guns that I could see and hear Suleiman Khan giving his orders, and was almost in front of them when the gunners were commanded to fire grape into a seething crowd which appeared to be advancing on the Matamet's pavilion. It consisted mainly of a Persian regiment, which, having failed to form, was failing back in disorder. It was afterwards found to have lost a number of men from this volley.

(Layard 1894; 261-2)

They were unable to accomplish their mission, only managing to rescue the Khan’s brother Au Kerim, but the losses to the Persians were such that they were forced to withdraw. Khatun-jan decided that the group should seek the protection of relatives in the Zagros but these proved to be faithless—one of them even clapped Layard and Au Kerim in chains. He thought his hour had come:

I was labouring under too much. anxiety, and overwhelmed by too many thoughts to be able to sleep. To he murdered in cold blood by a barbarian, far away from all help or sympathy, the place and cause of one's death to he probably forever unknown, and the author of it to escape with impunity, was a fate which could not be contemplated with indifference.

(Layard 1894: 272)

But the wife of his captor, shamed by her husband’s breach of faith, helped the pair to escape— although his companion was later recaptured when his horse threw him.

By this time, Layard had decided he had done what he could to help his friends and decided to make his way back to Mesopotamia. Even so, he was caught by the Persians and was their “guest” for a time before escaping. It was now the hottest part of the summer and Layard spent several weeks travelling through a scorched landscape before reaching the Tigris near Basra. As luck would have it, there was a British merchantman anchored in the river—one of its sailors later recorded his shock at being hailed in firm Queen’s English by what appeared to be a particularly ragged native. After a brief rest (and a hot bath) he headed north to Baghdad only to be robbed repeatedly along the way and narrowly escaping death on one occasion. He arrived in Baghdad, naked and with bleeding feet, in the middle of the night and passed out next to its locked gates:

A crowd of men and women bringing the produce of their gardens, laden on donkeys, to the bazaars, were waiting for the moment when they were to he admitted. At length the sun rose and the gate was thrown open. Two cawasses of the British Residency, in their gold-embroidered uniforms, came out, driving before them with their courbashes the Arabs who were outside, to make way for a party of mounted European ladies and gentlemen. It was the same party that, on my previous visit to Baghdad, 1 had almost daily accompanied on their morning rides. They passed close to me, but did not recognise me in the dirty Arab in rags crouched near the entrance, nor, clothed as I was, could I venture to make myself known to them. But at a little distance behind them came Dr. Ross. I called to him, and he turned towards me in the utmost surprise, scarcely believing his senses when he saw me without cover to my bare head. with naked feet, and in my tattered abba.

It was weeks before he could walk normally again—although he later recovered his clothes and other  effects. Some time later, he came across Mehemet Taki Khan, shackled to a dungeon wall in the town of Shuster and his womenfolk in a squalid little house:

effects. Some time later, he came across Mehemet Taki Khan, shackled to a dungeon wall in the town of Shuster and his womenfolk in a squalid little house:

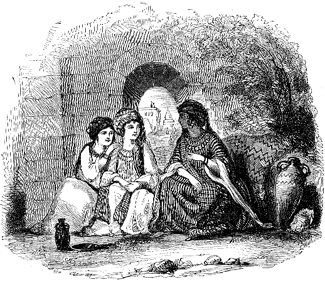

I spent some hours daily with Khatun-jan Khanum and her companions in misfortune, who treated me as if I were one of Mehemet Taki Khan's family. I learnt much from them relating to female life and customs among Shi'a Musulmans. Their affectionate gratitude to me in return for my sympathy, which was all I could give them, was most affecting. I found in these poor sufferers qualities and sentiments which would have ennobled Christian women in a civilised country.

(Layard 1894: 348)

The whole family was eventually sent to Teheran, the beautiful younger sister dying along the way. There Mehemet Taki Khan eventually died in 1851.

Suggested Reading

| Larsen, Mögens T. | (1996) | The Conquest of Assyria |

| Layard, A.H. | (1849) | The Monuments of Nineveh |

| (1853) | Discoveries among the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon | |

| (1867) | Nineveh and Babylon A narrative of a second expedition to Assyria, during the years 1849, 1850, and 1851 | |

| (1860) | Inscriptions in the Cuneiform Character, from Assyrian monuments, discovered by A. H. Layard, D.C.L. | |

| (1887) | Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana, and Babylonia | |

| (1894) | A Handbook of Rome and its Environs | |

| (1903) | Autobiography and Letters from his childhood until his appointment as H.M. Ambassador at Madrid | |

| Lloyd, Seton | (1981) | Foundations in the Dust |