The Central Court and Throne Room

The Central Court

The Central Court is clearly the main focus of activity in the palace—if fact, it is the hallmark of every Minoan palace. All of the entrances lead to it and all of the important sets of rooms—the throne room, the principal shrine, the royal apartments—open onto it. It measures approximately 25 x 50 metres—roughly the same dimensions as at the smaller palaces at Mallia and Phaistos but significantly larger than the one at Zakro. These last three are rectangular, inasmuch as we can tell from what survives. This may well have been the case at Knossos too, but here the eastern side has been very much disturbed and what survives is very irregular.The surface of the court was paved with flagstones—there is a sizeable patch preserved in the northwest corner.

Of course, courtyards such as these serve a necessary function in large buildings, providing air and light to the interior as well as enabling easy access from one part to another. However, the standardized size of the courts in each of the palaces suggests a specific, formal use. Not only do most of the ceremonial and cult rooms open off them, but frescoes found elsewhere in  the palace show large numbers of people in just this sort of setting.

the palace show large numbers of people in just this sort of setting.

One thing is fairly certain—they were not used for bull-leaping. That would have been suicidal in an arena with sharp corners and slippery pavement. The bullrings used in Spain have no corners. They are are circular of oval, and are covered with sand to give firm footing. The central court at Knossos has been covered up in order to protect the surface but at Phaistos (left) it is still visible.

Only the façade on the western side of the court was well enough preserved to give a fair idea of its original appearance. It is very open with a number of doorways, staircases and a portico of square pillars at the southern end. These gave access to the principal cult and ceremonial areas of the palace. The eastern side, by contrast, is an almost solid block with only one entrance.

The Throne Room Suite

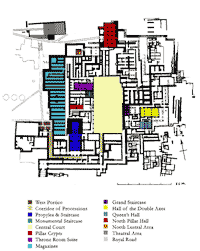

There is a clear distinction between the formal rooms on the west side of the central court and the magazines behind them. They were separated from each other by the Long Corridor and access to the latter was strictly controlled. The Throne Room Suite is located at the north end of the Central Court, next to what Evans called the Stepped Portico, and consists of an Antechamber, which opens directly onto the court, the Throne Room itself, and an Inner Sanctuary beyond.

From the way in which the walls surrounding it have been interrupted to accommodate it, it is clear that the suite is a late addition, undoubtedly dating to the period of Mycenaean occupation since nothing similar has been found at any of the other palaces. The ceramic evidence, which includes sherds of Palace Ware from the Third Palace Period, would seem to support this conclusion. All traces of pre-existing rooms, apart from a section of curving wall in the north-eastern corner, were “abruptly cut off” according to Evans, and the new suite was built directly on top of sub-Neolithic deposits. Such ruthlessness suggests (strongly) that one ideology had given way to a new and apparently irreconcilable one.

Plan of the Throne Room Suite (after Evans, Palace of Minos IV, figure 877)

The Antechamber

The Antechamber is accessible from the court by a set of four double doors. This type of multiple opening is known as a polythyron or a ‘pier-and-door partition’ and is a regular feature of cult installations and other ceremonial rooms. Evans found the sherds used to date the construction beneath one of the threshold slabs.

The room itself was reached by a flight of four steps that descend from the courtyard. The paved floor was made up of a central square of irregular ironstone slabs surround by gypsum flagstones. There were gypsum benches up against the north and south walls, with space for a throne up against the north wall—Evans found a deposit of ash and carbonized wood there, which he thought may have been its remains. Traces of wall paintings have survived—the foot of a bull resting on an imitation marble dado. When he restored the antechamber, Evans placed a large basin of purple gypsum, which he had found in a nearby passage, in the middle of the room.

The room itself was reached by a flight of four steps that descend from the courtyard. The paved floor was made up of a central square of irregular ironstone slabs surround by gypsum flagstones. There were gypsum benches up against the north and south walls, with space for a throne up against the north wall—Evans found a deposit of ash and carbonized wood there, which he thought may have been its remains. Traces of wall paintings have survived—the foot of a bull resting on an imitation marble dado. When he restored the antechamber, Evans placed a large basin of purple gypsum, which he had found in a nearby passage, in the middle of the room.

In the north-eastern corner of the antechamber was an opening, tucked in behind the curving stretch of wall that Evans thought belonged to the first palace built on the site that led to a winding flight of stairs (see the plan, above). Presumably it led to the rooms above the Throne Room.

Interior of the Throne Room from the Antechamber

The Throne Room

A rather wide doorway led into the Throne Room. Scuff marks on the floor and traces of a door jamb show that originally there was a polythyron of two double doors here. The arrangements were rather similar to those in the antechamber— there were benches along the walls with a gap  towards the middle of the northern wall. In this case, however, the throne was made out of gypsum, but was carved to be a detailed replica of a wooden original.

towards the middle of the northern wall. In this case, however, the throne was made out of gypsum, but was carved to be a detailed replica of a wooden original.

It stands just over 138 cm. tall, with its seat 48 cm. above the projecting base (slightly higher than a standard modern chair). The back was carved out of a single piece of stone and tilts back slightly so that the top is embedded in the wall plaster (left). It has an undulating outline with a rolled border and was probably painted with elaborate designs The seat was well designed for the comfort of the occupant. The surface was hollowed out and there were broad grooves on the front edge to accommodate the thighs. The front ‘legs’ are formed by a pair of arched pilasters that have a plant-like appearance, thanks to the small ‘buds’ that appear to grow from their inner sides. Below the arch is what Evans calls a “counter-arch,” undoubtedly derived (as were the cross-pieces in the sides) from the need for more support in the original version.

The throne was framed by painted palm trees and a pair of crouching griffins shown against a backdrop of papyrus plants and wavy, decorative bands. Another pair of beasts flanked the door at the back of the room, to the right of the throne. Some of the decoration still clung to the wall next to the throne but most of it had fallen onto the floor. The griffins, a mythical combination of an eagle (or hawk) and a lion—two beasts that  symbolize kingship in the ancient Near East—are wingless, which is quite unusual. The best preserved example was the one on the left side of the doorway but the others were pretty much identical. Its crest was a crown of elaborately curving feathers of various colours, imitating the ruff of the eagle. It also wears what appears to be a scalloped collar, beneath which is a spiral wrapped around a blue rosette and a garland of papyrus blossoms. Along the beast’s back is a string of decorative blue ovals and red dots, perhaps representing beads but it is difficult to be sure.

symbolize kingship in the ancient Near East—are wingless, which is quite unusual. The best preserved example was the one on the left side of the doorway but the others were pretty much identical. Its crest was a crown of elaborately curving feathers of various colours, imitating the ruff of the eagle. It also wears what appears to be a scalloped collar, beneath which is a spiral wrapped around a blue rosette and a garland of papyrus blossoms. Along the beast’s back is a string of decorative blue ovals and red dots, perhaps representing beads but it is difficult to be sure.

In Minoan Crete, the griffin is frequently associated with the goddess but never with a male figure, so it is probably better to think imagine a priestess rather than a king seated on the throne. Nanno Marinatos suggests that the priestess impersonated the Goddess in the enactment of an epiphany, a bit of theatre in which she ‘appeared’ to the people during  highly charged religious ceremonies. On the other hand, painted griffins flank the throne at the mainland Greek palace at Pylos and are generally considered to be the equivalent of an heraldic device for the royal family. This would certainly fit in well with the scenario of a mainland takeover of Knossos during this period.

highly charged religious ceremonies. On the other hand, painted griffins flank the throne at the mainland Greek palace at Pylos and are generally considered to be the equivalent of an heraldic device for the royal family. This would certainly fit in well with the scenario of a mainland takeover of Knossos during this period.

The religious nature of the setting is reinforced by the stylized depiction of incurved altars on either side. Near the doorway to the antechamber, Evans found a number of alabastra—squat, flat-bottomed vessels used for oil (right), perhaps the perfumed type used to anoint. Nearby were the crushed fragments of a pithos, causing him to believe that they were in the process of being filled when the ceiling came crashing down during the earthquake that finally destroyed the palace.

Opposite the throne, on the south side of the room, was another bench behind which was a balustrade and a Lustral Basin. The rear of the bench hadsockets for three wooden columns, of which only carbonized traces survived. A dog legged flight of six steps led to the basin, which, as  wall typical at Knossos, was lined with stone and apparently waterproofed with plaster. Evans believed that, in this case, the installation was used to anoint votaries before they approached the deity. However, although amphorae used as containers for oil were found nearby, none were actually found in the lustral basin, and other explanations are possible.

wall typical at Knossos, was lined with stone and apparently waterproofed with plaster. Evans believed that, in this case, the installation was used to anoint votaries before they approached the deity. However, although amphorae used as containers for oil were found nearby, none were actually found in the lustral basin, and other explanations are possible.

Directly overhead was a Lightwell, an opening in the ceiling that probably continued to the roof. When Evans cleared the lustral basin he found quite a number of objects, including bits of crystal and gold leaf, that he believed had been thrown in from the room above. The area had been thoroughly looted soon after the final destruction and most of the precious objects had been removed. Some of the crystal pieces he thought belonged to an inlaid gaming board, similar to one found elsewhere in the palace and others found in Egypt. Others were fragments of crystal bowls or from pieces of jewellery. Access to this ‘loggia’ was either by way of the monumental staircase adjacent to the Throne Room or by the small stairway adjacent to the Antechamber.

Reconstruction of the Throne Room (Edwin J. Lambert)

The Inner Sanctuary

The fact that it was flanked by griffins suggests that the door at the back of the room was of considerable importance. Evans labelled it the Inner Shrine and it may have been used as a robing room where the principal party would retire at certain points in the ceremony to change costume or simply to rest. A silver armlet and some gold foil was found on a raised altar directly opposite the door. Their appearance or reappearance, framed by the sacred animals, would have been quite dramatic.

The Service Section

To the north and west, but not directly connected to the Throne Room, was a suite of rooms that Evans describes as the Service Section. The only entrance was from the corridor running to the north, where Evans found the purple ‘font’ that he restored to the Antechamber. He believed that the suite was “part of the women’s domain” but his grounds for this would raise a few eyebrows today.

On the floor of the first room he found a stone seat, similar in its contours to the gypsum throne but, in his opinion, designed to accommodate a more ample posterior. However, the fact that the slab (and a  similar example found nearby) is a mere 5 inches (12.7 cm) high suggests it may have served some other purpose. Nevertheless, Evans saw it as the seat of a female porter, who squatted on it while guarding the entrance to this part of the palace. The adjoining room had a low ledge of stone blocks that might have served as a bench.

similar example found nearby) is a mere 5 inches (12.7 cm) high suggests it may have served some other purpose. Nevertheless, Evans saw it as the seat of a female porter, who squatted on it while guarding the entrance to this part of the palace. The adjoining room had a low ledge of stone blocks that might have served as a bench.

A rather narrow doorway connected it to another furnished with a gypsum drum about 67 cm. tall and slightly larger in diameter, carved with a pair of quadrants on the upper surface (see plan, above). Opposite it was a thin gypsum, semi-circular ledge that had been cemented into the wall at about the same height. It is impossible to say what they were used for but Evans suspects some sort of domestic function. In the doorway he found a clay seal impression of a rather youthful looking priest (to judge from his robe and the sacrificial axe he is shouldering). Behind him is a dolphin, symbolizing the fertility of the sea.

Little is known about the rooms that ran along the western side of the Throne Room Suite apart from the last one (left), which may have been a kitchen of some sort. There was a seat, virtually identical to the one described above, except that it was found firmly cemented into the floor along the south wall. In front of it was a rather curious object, a low, plaster coated table that was semi-circular at one end and squared at the other. There was a bowl-shaped hollow at the rounded end and a shallow trough at the other. It may have been used in the preparation of food but the surface was inappropriate for grinding, pounding or chopping. Evans suggested that perhaps some sort of liquids were processed. A low, stepped dais ran along the inner wall of the room. In the centre was a bowl-shaped hollow, similar to that in the table. Oddly for a kitchen area, there are apparently no cooking facilities.

Unless otherwise stated, all black & white photos of Knossos are from The Palace of Minos by Arthur Evans and are reproduced here courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University