The Stones of Stenness were partly excavated by Graham Ritchie in the 1970’s and some of the surrounding area was examined by Colin Richards and his team in the late 1980’s and early 90’s as part of the Barnhouse project. They stand at the centre of a circular henge—a ditch with an external bank—about 44 metres across. The fill of the ditch, which was about 7 metres wide and 2 metres deep, produced some animal bone (mainly domestic cattle and sheep but also some belonging to dogs or wolves). There were also some sherds of Grooved Ware, suggesting the remains of sacrificial offerings or ritual feasts (or both). A radiocarbon date from one of the bones has produced a date of 2356 bc ± 65, which calibrates to a little over 3000 BC.

The causewayed entrance to the henge faces north-northeast, in the general direction of the neolithic settlement at Barnhouse, which lies about 150 metres away on the shore of Loch Harray.

The Stone Circle

There seems to have been only the one entrance, which would make Stenness a Class I henge but, given that no digging has taken place in much of the rest of the site, this conclusion can only be tentative. Excavation of the terminals of the ditch revealed that the one on the west had been extended at some point to make the entrance narrower. Perhaps this related in some way to the internal structures within the circle that are aligned to the opening. As far as the outer bank, typical of a henge, is concerned, although it is clearly visible in 18th century prints and plans, it has been all but obliterated by subsequent ploughing. However, enough remains, according to Ritchie, to indicate that it was about 6.5 metres across.

are aligned to the opening. As far as the outer bank, typical of a henge, is concerned, although it is clearly visible in 18th century prints and plans, it has been all but obliterated by subsequent ploughing. However, enough remains, according to Ritchie, to indicate that it was about 6.5 metres across.

The stone circle (an ellipse really) is approximately 30 metres in diameter and had long been assumed, on the basis of its curvature and the spacing of the surviving stones, stumps and stone sockets, to have been made up of 12 standing stones. However, only four stones [Stones 2, 3, 5 & 6] were still standing in the 18th century, when the earliest reliable descriptions were recorded, with a fifth lying on its side. But in December of 1814 the site was vandalized by a tenant farmer who leased the land, one Captain W. MacKay (a ‘ferrylouper’), began to destroy them “for the purpose of strengthening the fields”— although the procurement of building material for new cattle byres. One of the stones was toppled over and another [Stone 6] was broken into pieces. The fallen stone [Stone 5] was re-erected in 1907 as part of a plan to restore the site and joined the two survivors [Stones 2 & 3]. The socket for it still had most of the original packing material and the stone was a perfect fit. In the process, a hitherto unknown slab was discovered underneath the turf, set up in a nearby empty socket and packed in concrete. This stone [Stone 7] is distinguished by its crooked shape and is much smaller than the others, so there is some debate over whether or not it was part of the original circle. However, it did fit the socket rather nicely. Moreover, we have no idea of what went into the selection process of the original builders.

Watercolour of the Stones of Stenness by John Cleveley (1772).

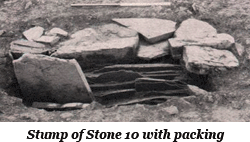

The tallest surviving stone [Stone 2] is 5.7 metres high, a maximum of 1.5 metres in breadth and about 25 cm. thick and, like many of the standing stones in Orkney, it was sharply truncated at the top. Stone 3 is 5.3 metres in height, 1.35 metres across and up to 38 cm. in thickness. Stone 5, once re-erected in  its original socket stood 4.8 metres high, was 1.55 metres across and 45 cm. thick. The stumps of four more uprights [Stones 4, 8 10 & 11] have survived and Ritchie’s investigations in the 1970s uncovered sockets for another three [Stones 1, 6 & 9]. However, the socket for Stone 9 had been backfilled shortly after it was dug and the lack of packing material suggests it had never been used. The position of Stone 12 is inferred by the spacing of the others but upon excavation the ‘socket’ turned out to be much too small to hold a large stone. It has been suggested that the original structure was a ring of tree trunks or wooden posts and that these were later replaced by stones as they rotted away. Something similar is evident during the Archaic Period in Greece at the Temple of Hera at Olympia, ca. 700-480 BC, where the original wooden columns were gradually replaced by stone versions as necessary. It was considered a most pious act and was undertaken by wealthy individuals or families as a sign of their status.

its original socket stood 4.8 metres high, was 1.55 metres across and 45 cm. thick. The stumps of four more uprights [Stones 4, 8 10 & 11] have survived and Ritchie’s investigations in the 1970s uncovered sockets for another three [Stones 1, 6 & 9]. However, the socket for Stone 9 had been backfilled shortly after it was dug and the lack of packing material suggests it had never been used. The position of Stone 12 is inferred by the spacing of the others but upon excavation the ‘socket’ turned out to be much too small to hold a large stone. It has been suggested that the original structure was a ring of tree trunks or wooden posts and that these were later replaced by stones as they rotted away. Something similar is evident during the Archaic Period in Greece at the Temple of Hera at Olympia, ca. 700-480 BC, where the original wooden columns were gradually replaced by stone versions as necessary. It was considered a most pious act and was undertaken by wealthy individuals or families as a sign of their status.

The Central Setting

Recreating the stone circle. The willing volunteers are all standing atop a marker for one of the missing stones.

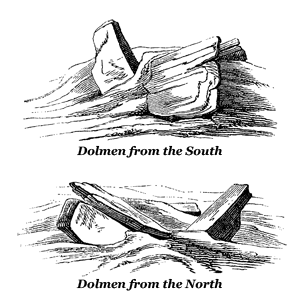

On the main axis of the circle, which runs from the north entrance through the centre of the site, was an arrangement of features that had been added at various times during its (pre-)history. The first setting  encountered today is a setting of stones known as “the dolmen”, the earliest record of it is in a watercolour by John Cleveley published in 1772. It depicts two small uprights standing side by side and a third, larger one leaning up against them. Sir Walter Scott, who visited the islands some four decades later, thought it was a ruined altar used for human sacrifice. When the site was restored by the Office of Public Works in 1907, the consensus was that it was meant to be a dolmen (aka. cromlech), a type of tomb common in Ireland and South-western Britain as well as Brittany in northwest France. The word ‘dolmen’ means “table” in the Breton language and they were essentially made up of large flat slabs supported by three or more uprights. With that in mind, the restorers straightened up the two existing uprights, set them in concrete, and brought an additional stone to the site and set it up facing them and aligned with the gap between them. It would seem that, while they were about it, they levelled the tops of the surviving stones to a height of about 1.90 metres and then laid the large slab across the top of all three. Despite all of this manoeuvring, early plans indicate that the original pair of uprights are in their original positions, aligned edge to edge roughly along the north-south axis of the circle.

encountered today is a setting of stones known as “the dolmen”, the earliest record of it is in a watercolour by John Cleveley published in 1772. It depicts two small uprights standing side by side and a third, larger one leaning up against them. Sir Walter Scott, who visited the islands some four decades later, thought it was a ruined altar used for human sacrifice. When the site was restored by the Office of Public Works in 1907, the consensus was that it was meant to be a dolmen (aka. cromlech), a type of tomb common in Ireland and South-western Britain as well as Brittany in northwest France. The word ‘dolmen’ means “table” in the Breton language and they were essentially made up of large flat slabs supported by three or more uprights. With that in mind, the restorers straightened up the two existing uprights, set them in concrete, and brought an additional stone to the site and set it up facing them and aligned with the gap between them. It would seem that, while they were about it, they levelled the tops of the surviving stones to a height of about 1.90 metres and then laid the large slab across the top of all three. Despite all of this manoeuvring, early plans indicate that the original pair of uprights are in their original positions, aligned edge to edge roughly along the north-south axis of the circle.

The dolmen idea was generally dismissed by scholars and the spurious stone was finally removed in 1972. The ‘table’ stone, which measures 2.74 x 1.99 x 0.49 metres, was laid on the ground in front of the surviving pair (left) but nowadays it is widely believed that it originally stood upright, in more or less the same position as the stone added in 1907. That would certainly be consistent with the angle at which it is depicted in the early drawings. Unfortunately, if there had been a socket there it was destroyed by the construction of the concrete foundation bed of the later addition. The resultant setting would, according to Aubrey Burl, have resembled the arrangement found at the end of a typical stalled cairn—a pair of side slabs and a back stone. He calls this feature a cove after a similar arrangement found at Avebury and believes that it represents a transference of rites of the dead from inside the tombs and into the open. If Burl is correct in his assumption that the ‘cove’ is funereal in nature, then the link between it and Maes Howe is understandable. Interestingly, if you project the same line in the opposite direction it is aligned directly to the standing stone at Deepdale on the western shore of Loch Stenness.

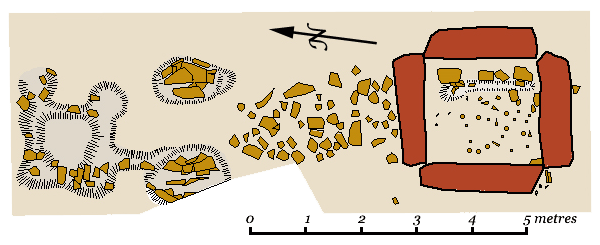

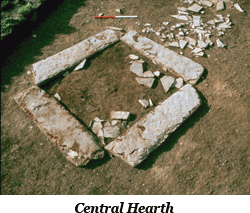

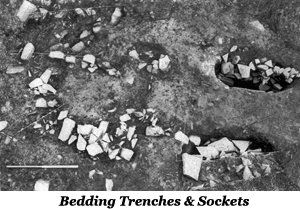

At the centre of the site Ritchie’s team uncovered a roughly square setting, 2.1 x 1.9 metres, of fairly substantial stone slabs  set in individual bedding trenches. They look like the hearths in the houses at Skara Brae or Barnhouse and contained a deposit of ash and burnt bone. Hearths were sacred places in ancient Europe (as, indeed, they were elsewhere), representing the security of the home and were worshipped as deities in their own right. Careful investigation revealed that the ‘hearth’ was not the first structure to occupy this space (see the plan below). The remains of what appear to be the footing for a pole supported by a wooden brace were found in the fill. Some sort of totem pole commemorating the group ancestors is one possible interpretation or perhaps a representation of the tree of life. Whatever it was, it clearly predated the construction of the hearth.

set in individual bedding trenches. They look like the hearths in the houses at Skara Brae or Barnhouse and contained a deposit of ash and burnt bone. Hearths were sacred places in ancient Europe (as, indeed, they were elsewhere), representing the security of the home and were worshipped as deities in their own right. Careful investigation revealed that the ‘hearth’ was not the first structure to occupy this space (see the plan below). The remains of what appear to be the footing for a pole supported by a wooden brace were found in the fill. Some sort of totem pole commemorating the group ancestors is one possible interpretation or perhaps a representation of the tree of life. Whatever it was, it clearly predated the construction of the hearth.

Between the dolmen or cove and the hearth, Ritchie uncovered what appears to be a roughly square arrangement of bedding trenches and the sockets for a pair of standing stones . There were circular depressions in the corners of the former that may have once held posts and Ritchie believes that they were the remains of a mortuary structure, perhaps a platform where corpses were laid out to rot before the bones were  placed in a tomb. In the years since, excavations have taken place at the nearby settlements of Barnhouse and the Ness of Brodgar which has altered perceptions somewhat. Each of these sites has produced a large, ceremonial building, Structure 8 at Barnhouse; Structure 10 at the Ness, with features comparable to those at Stenness. Colin Richards, the excavator of Barnhouse, believes that the original construction at Stenness was just such a building. Rather than a mortuary structure, Richards believes these elements represented a dismantled ‘threshold’ hearth flanked by upright, portal stones in Structure 8 at the former site. The contour plan of Stenness shows a doming in the central area that is suggestive of the shape a rectilinear building with rounded corners. Given the narrowness of Ritchie’s trench it is hard to be certain but there is a spread of stone to the east and west that may represent the debris from robbed out walls, perhaps double walls as at the Barnhouse and Ness of Brodgar structures.

placed in a tomb. In the years since, excavations have taken place at the nearby settlements of Barnhouse and the Ness of Brodgar which has altered perceptions somewhat. Each of these sites has produced a large, ceremonial building, Structure 8 at Barnhouse; Structure 10 at the Ness, with features comparable to those at Stenness. Colin Richards, the excavator of Barnhouse, believes that the original construction at Stenness was just such a building. Rather than a mortuary structure, Richards believes these elements represented a dismantled ‘threshold’ hearth flanked by upright, portal stones in Structure 8 at the former site. The contour plan of Stenness shows a doming in the central area that is suggestive of the shape a rectilinear building with rounded corners. Given the narrowness of Ritchie’s trench it is hard to be certain but there is a spread of stone to the east and west that may represent the debris from robbed out walls, perhaps double walls as at the Barnhouse and Ness of Brodgar structures.

Barnhouse. Structure 8

On the opposite side of the hearth (see plan) there is a group of five pits [Pits A-E] the largest of which is over a metre across and some 60cm deep (see the main plan). Ritchie found some stone slabs when he cleared the pits and suggests that they may well have been lined with stone. A pot had been set in one of them and others contained carbonized material including cereal grains, which have been dated to the first century AD. At that time (during the Iron Age) European farmers dug shafts and pits in which they placed offerings to the gods of the earth and underworld, and something similar may well have been going on here.

Construction

It is impossible to say for certain what the exact sequence of construction was but Ritchie believes it would have been easier to move the stones into position before the encircling ditch was cut out of the rock, but this need not be much of a factor considering the distance the stones had been dragged from their original quarry. There are a number of these in this part of Orkney that could have been the source. Vestrafiold, where similar stones can still be seen lying on the hillside, is the most notable of these. The effort involved in that operation was enormous— a total of some 50,000 man-hours at least— and would have called on labour from a fairly extensive area if the project was undertaken in one go. Of course the work would have been spread out if the monoliths were erected individually and brought to the site from different quarries at different times.

As far as archaeometric dating is concerned, bone from the bottom of the ditch gave a radiocarbon date of 3040 BC, while some charcoal from the hearth dates to about 2900 BC. Decomposed wood from the timber structure has provided a rather iffy date that calibrates as “sometime between about 3000 and 1000 BC” (my quotes). The margin of error is too wide to allow for any firm conclusions about the structural order at the site. Only further excavation can settle the matter.

View from Stenness to the former causeway with the Ring of Brodgar in the distance

A Processional Way?

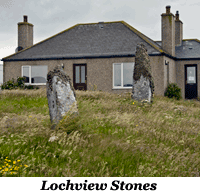

A short distance away to the northwest, at the near end of the causeway that once linked Stenness and Brodgar, is a solitary monolith 5.6 metres tall known as the Watch Stone. Originally it was one of a pair of stones that probably served as a sort of portal linking the two great circles. In 1930 the stump of its companion was uncovered about 13 metres to the southwest, near the edge of Loch Stenness. It is widely believed that both were part of a stone lined avenue connecting Stenness and Brodgar but, if there was such an avenue, so many stones have disappeared that it would be impossible to prove. A pair of stones are located outside the cottage at Lochview, on the other side of the causeway, and there is the so-called ‘Comet Stone’ along with its companions (represented by two stumps) on the approach to the Ring of Brodgar.

The Odin Stone

Until 1814 there was a perforated monolith known as the ‘Stone of Odin’ about 140 metres to the north of the site. According to antiquarian accounts it was about 8 feet (2.5 metres) tall by 3½ feet (1 metre) broad and was perforated near the base. When Captain Mackay began his campaign against the stones in Christmas of that year, he decided to start with the Odin Stone and ordered it to be pulled over and broken up with hammers. His actions caused outrage among the locals who attempted, on at least two occasions, to burn down his house. Their anger arose from the fact that the stone was believed to hold magic powers and played an important role in the life of the community. It protected the health of newborns who were passed through the perforation and was thought to prevent certain diseases if you stuck your head through it. It also sanctified agreements but it was particularly revered for the role it played in marriage rituals.

The Odin Stone (right) and the Watch Stone

When James Ker visited the islands in the 1780’s he noted in his log a conversation he had with a certain Dr. Groat and says that, near the stone circle,

are two large Stones standing singly, the shortest perforated with a hole near the Edge large enough to admitt a Man's Head, thought to have been used to bind the Victims to and called therefore the Stone of Sacrifice…. Dr Groat says that about 20 years ago he remembers it customary with Lovers, when Circumstances did not admitt of their marrying immediately in a publick manner: to put their Hands thro' on opposite Sides and joining them Swear Fidelity to each other, likewise that whenever Circumstances would admitt their marriage should be publickly solemnised. He adds, that after this they proceeded to Consummation without further Ceremony & that no Instance was ever known of their refusing to keep their agreement afterwards.

A resistivity survey of the area directly north of the stone circle revealed anomalies that turned out to be the empty sockets of three standing stones. Excavation revealed that, unlike the other two, the southernmost contained fill very similar to the overlying plough soil suggesting that the stone had been removed relatively recently and is therefore the likeliest candidate for the Odin Stone. If that was the case then the Odin Stone was originally one of a pair set with their broad sides flanking the gap—much the same arrangement as the ‘dolmen’ at Stenness itself and the opposed pairs of uprights in the chambers of ‘stalled cairns’ (see article Orkney-Cromarty Cairns).

Further Reading

| Burl, Aubrey | (1993) | From Carnac to Callanish |

| (2000) | Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany | |

| Cunliffe, Barry | (2001) | Facing the Ocean: The Atlantic and its Peoples |

| Garnham, Trevor | (2004) | Lines on the Landscape, Circles from the Sky |

| Renfrew, Colin | (1979) | Investigations in Orkney, Society of Antiquaries of London, Research Report No. 38 |

| Renfrew, Colin (edit.) | (1985) | The Prehistory of Orkney |

| Richards, Colin (edit.) | (2005) | Dwelling among the monuments |

| (2013) | Building the Great Stone Circles of the North | |

| Ritchie, Anna | (1996) | Orkney |

| Ritchie, J.N.G. | (1978) | ‘The Stones of Orkney,’ Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 107 |

| Scarre, Chris | (2007) | The Megalithic Monuments of Britain and Ireland |

| Thom, Alexander | (1970) | Megalithic Lunar Observatories |

| Wickham-Jones, Caroline | (2006) | Between the Wind and the Water, World Heritage Orkney |