By the death of the Emperor Domitian in AD 96, Britain had been a Roman province for over half a century but the conquerors found it exceedingly difficult to establish their control. The divine Claudius' initial victories in AD 43 had been due to the training and professionalism of the imperial  legions coupled with some astute political manoeuvring among the fractious natives. Many tribes willingly offered themselves up as Roman clients to preserve their own territory and to reap the benefits of Roman friendship but with the accession of Nero things changed dramatically for the worse. A corrupt and oppressive provincial administration led to the rebellion of the Iceni queen Boudicca in AD 60 and the destruction of key Roman settlements at Colchester (Camulodunum), London (Londinium) and St. Albans (Verulamium). Although the revolt was quickly and brutally put down, the new province was devastated and both sides were utterly exhausted. This, coupled with civil war in Rome brought offensive operations in Britain to a halt, with the north and the west still unsubdued. As for Boudicca, her statue (right) now stands on the Thames Embankment, at the heart of the city she once obliterated.

legions coupled with some astute political manoeuvring among the fractious natives. Many tribes willingly offered themselves up as Roman clients to preserve their own territory and to reap the benefits of Roman friendship but with the accession of Nero things changed dramatically for the worse. A corrupt and oppressive provincial administration led to the rebellion of the Iceni queen Boudicca in AD 60 and the destruction of key Roman settlements at Colchester (Camulodunum), London (Londinium) and St. Albans (Verulamium). Although the revolt was quickly and brutally put down, the new province was devastated and both sides were utterly exhausted. This, coupled with civil war in Rome brought offensive operations in Britain to a halt, with the north and the west still unsubdued. As for Boudicca, her statue (right) now stands on the Thames Embankment, at the heart of the city she once obliterated.

With the accession of Vespasian to the imperial throne in AD 68 (the ‘Year of the Four Emperors’), stability returned to the empire and a more vigorous policy was adopted. In AD 77, Gnaeus Julius Agricola was appointed as governor and within three years he had launched campaigns into Wales, Cumbria and Scotland. The tribes of Scotland proved stubborn opponents and it took a series of campaigns to pacify the country.

View of Bennachie from Easter Acquhorthies

The decisive battle was fought against the Caledonians at Mons Graupius (possibly Bennachie in Aberdeenshire), a hard-fought Roman victory. However, the defeated survivors escaped deep into the highlands where they would prove very difficult to pacify. Then, before the process was complete, Agricola was recalled by Domitian and regular campaigning was wound down. A line of fortifications, centred around a big legionary base at Inchtuthil, known as the Gask Frontier was established to control the exits to the glens which ran up into the highlands from Strathmore in Perthshire and to keep the tribes bottled up. Eventually this forward position was abandoned as war on the other frontiers of the Empire led to the withdrawal of one of the four legions stationed in Britain and the Roman presence in Scotland was limited to the area now known as the Borders, south of the Forth-Clyde line.

The Roman Army in Britain

When Claudius invaded Britain in AD 43 he took four full legions of Roman troops with him together with an equal number of auxiliary troops (including the bulk of the cavalry) from the provinces— perhaps 40,000 men altogether. By the 80's, the number had been reduced by a quarter with the withdrawal of one legion. The remaining three were

When Claudius invaded Britain in AD 43 he took four full legions of Roman troops with him together with an equal number of auxiliary troops (including the bulk of the cavalry) from the provinces— perhaps 40,000 men altogether. By the 80's, the number had been reduced by a quarter with the withdrawal of one legion. The remaining three were  based at Caerleon, Chester and York and formed what was to become the normal garrison of the province.

based at Caerleon, Chester and York and formed what was to become the normal garrison of the province.

The legion was the basic unit of the imperial army and consisted of about 5,400-6,000 men, all Roman citizens, under the command of a legate, a member of the Senatorial class appointed by the Emperor. Each legion was accompanied by an equal number of auxilia, non-citizens who provided cavalry and light troops, in containing 6 centuries of 80 men each (although from the end of the first century the first cohort had double centuries of 160 men each). There were also 120 mounted troops to act as messengers and scouts. The officers included 60 centurions and 6 tribunes.

Claudius' original force consisted of the II Augusta, the VIIII Hispana (not a typo), the XIV Gemina, and the XX Valeria Victrix. Of these, only the II Augusta was still serving in Britain in the fourth century—the others were replaced by other units over the years or, in the case of the VIIII Hispana, withdrawn altogether.

The Roman fort at Hard Knot, Cumbria

Roman Forts

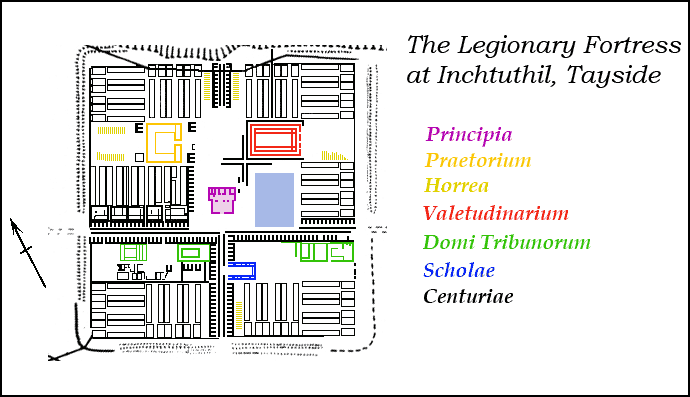

One of the hallmarks of the Roman army and the key to its success was the art of military engineering—roads and bridges to move men at speed over large distances, marching camps and fortified bases to protect them on campaign. To consolidate their grip on conquered territory, they simply made them permanent. A major fort was under construction at Inchtuthil near Dundee when the order came to withdraw from Scotland. The plan, which covers an area of 22 hectares can still be seen in aerial photos.

The Greek historian Polybius, writing in the second century BC, gives the best description of a typical Roman marching camp:

Whenever the army on the march draws near the place of encampments, one of the tribunes and those of the centurions who are in turn selected for this duty go ahead and survey the whole area where the camp is to be placed. They begin by determining the spot where the consul’s tent should be pitched... and on which side of this space to quarter the legions. Having decided this, they first measure out the area of the praetorium. Next they draw the straight line along which the tents of the tribunes are set up, and then the line parallel to this, which marks the starting-point of the encampment area for the troops. In the same way they draw up the lines on the other side of the Praetorium.... All this is done with little loss of time and the marking out is an easy task, since all the distances are regulated and are familiar. They then proceed to plant flags; the first on the spot where the consul’s tent is to stand, the second on that side of it which has been chosen for the camp, a third at the central point of the line on which the tribunes’ tents will stand, and a fourth on the parallel line along which the legions will encamp. These latter flags are crimson, but the consul’s is white. The lines on the other side of the praetorium are marked sometimes with flags of other colours, sometimes with plain spears. After this they proceed to lay out the streets between the various quarters, and plant spears to mark each street. The result is that when the legions on their march have arrived near enough to get a good view of the site, the whole plan quickly becomes familiar to everyone, as they can reckon from the position of the consul’s flag, and get their bearings from that. Everyone knows exactly which street and in which part of that street his tent will be situated, since every soldier invariably occupies the same position in the camp.

(Historia VI 41)

The Roman fort was essentially a marching camp translated to more permanent materials.

Inchtuthil was a typical fort of the period, of the sort that could be found throughout the empire. Roman soldiers were drilled until they could build them in their sleep. Their layout looks like a playing card, rectangular with rounded corners. The interior was arranged around a cruciform of two intersecting roads known as the via principalis and the via praetorium. Normally, the latter ran directly to the Headquarters Building (Principia) while the former ran across its front. The commanding officer's quarters (Praetorium) was located next door. Also nearby was the Officers Quarters (Domi Tribunorum), the Hospital (Valetudinarium), Granaries (Horrea) and Workshops (Fabrica). The Barracks (Centuriae) were arranged in neat rows all around the central area. The troops were still living in a temporary camp and construction of some of the buildings, most notably the Praetorium and the bath house, had not yet begun when the site was abandoned.

These buildings will be examined in more detail when we take a close look at some of the fortresses along the Wall.

Trajan

In AD 96 the reign of Domitian came to an end with the death of the emperor in a palace coup, apparently organized by his own wife. Although, according to the historian Suetonius, Domitian's final years amounted to a ‘reign of terror,’ by and large he had been a very capable ruler. He had actively suppressed many of the abuses which had caused discontent in the provinces and had drafted leading provincials into the Senate of Rome. The reign of Nerva (AD 96-8) marked the beginning of the period known at the “Five Good Emperors”. He began the practice of appointing his successor from among the best available men, whatever their origins. Nerva chose a military man, Marcus Ulpius Traianus (AD 98-117), as his heir. Trajan was a provincial, born in Italica in Spain to an Italian father and a Spanish mother, and had made a career in the military. It was the support of the army that was key to his selection.

In AD 96 the reign of Domitian came to an end with the death of the emperor in a palace coup, apparently organized by his own wife. Although, according to the historian Suetonius, Domitian's final years amounted to a ‘reign of terror,’ by and large he had been a very capable ruler. He had actively suppressed many of the abuses which had caused discontent in the provinces and had drafted leading provincials into the Senate of Rome. The reign of Nerva (AD 96-8) marked the beginning of the period known at the “Five Good Emperors”. He began the practice of appointing his successor from among the best available men, whatever their origins. Nerva chose a military man, Marcus Ulpius Traianus (AD 98-117), as his heir. Trajan was a provincial, born in Italica in Spain to an Italian father and a Spanish mother, and had made a career in the military. It was the support of the army that was key to his selection.

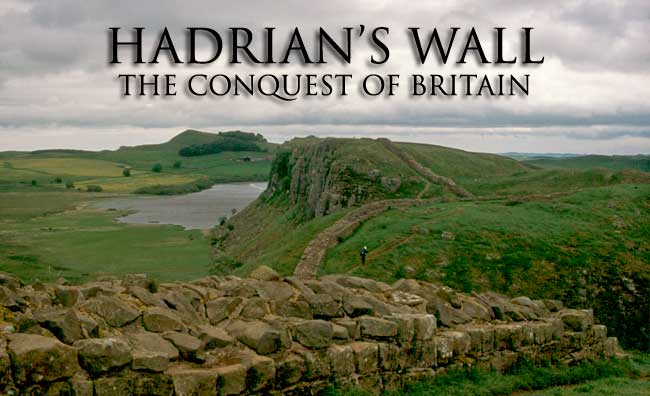

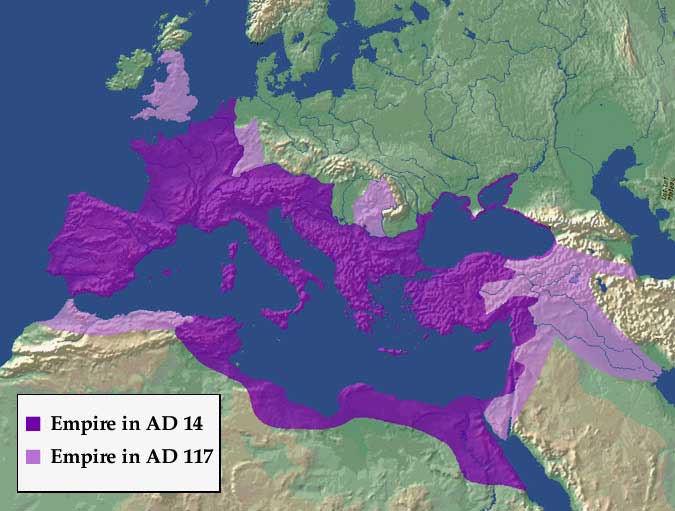

Trajan was a very aggressive emperor and carried the boundaries of the empire to its greatest extent. In the East he wrested Armenia and Mesopotamia away from the Parthian kings of Persia and in the West he added Dacia (Rumania) across the Danube. All of this activity on other fronts meant that the final conquest of Britain was going to have to wait for a while. There was a general pull-back of troops from beyond the Forth-Clyde Isthmus and a substantial reduction of troop strength in southern Scotland. The new provincial frontier ran along the Stanegate (Saxon for “stone road”) linking Corbridge and Carlisle, which dominated the two military routes to the north, one on either side of the Pennines.

The Roman Empire in the time of Trajan

Trajan continued the Flavian policy of ‘Romanisation’ in the subjugated parts of Britain, promoting the growth of cities and civic values among the British ruling class. Imperial patronage was responsible for a sudden flowering in monumental public architecture. In London (Londinium), a new and much larger basilica was built and a new forum laid out to serve as the administrative centre of what was by now the provincial capital. By the time of his death in AD 117, Trajan had won a great deal of respect for the Principate among the native population.

The Stanegate Frontier

Trajan's pursuit of a more forward policy meant that he thought of the current frontier as a springboard to further operations in the north, to regain control of territories recently abandoned and to complete the conquest of the island. The main legionary bases at Corbridge in the east and Carlisle in the west guarded the two main routes to the north. The Stanegate road was designed to link the two and provide a quick means of moving troops from one front to the other. It was to be protected by a system of forts, fortlets and watchtowers. Unfortunately, there has only been a very limited amount of research conducted on the forts along the road and, in the absence of accurate dating, it is impossible to be certain whether or not they were all contemporary. They were apparently of the standard turf-and-timber type that characterized the conquest period when the emphasis was on speed of construction. Those that have been excavated, Corbridge and Vindolanda, were later rebuilt in stone and much of the earlier material has been lost.

Stanegate at Corbridge

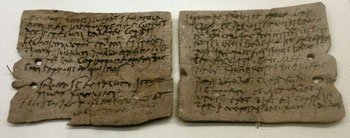

At Vindolanda, the soggy remains of a large fort, possibly dating to the time of Agricola, with a turf wall and timber palisade were uncovered beneath the later structures. The waterlogged deposits produced large amounts of organic material in and near what may have been the Commander's house. Large numbers of animal bones were recovered along with wooden implements and textiles. More than 200 shoes in a variety of styles and sizes (including women's and children's)—all made at the site. Over 400 wooden writing tablets were also found in 3 separate deposits (90-100 AD; 100-105 AD; and 105-120 AD). The texts mainly consist of official reports—records of supplies issued or requested—and letters. They indicate that the IIIrd and IXth cohorts of Batavian auxiliaries formed the garrison of the fort and there are records of their provisions, duty rosters, advances on pay and all of the other details of garrison life. One official report refers to the natives:

…the Britons are unprotected by armour. There are very many cavalry. The cavalry do not use swords nor do the wretched Britons (Brittunculi) take up fixed positions in order to throw their javelins.

Modern Brittunculi at Vindolanda Fort

An exceptional letter gives rare glimpse into life on the frontier. It was written to Sulpicia Lepidina, the wife of Flavius Cerialis, the garrison commander, by Claudia Severa, the wife of Aelius Brocchus who must have commanded a nearby garrison:

Claudia Severa to her Lepidina, greetings. On the third day before the Ides of September (i.e. the 10th), sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival, if you come.

Give my greetings to your Cerialis. My Aelius and my little son send you their greetings.

[then, in a second hand—presumably her own, rather than a secretary's]

I shall expect you, sister. Farewell, sister, my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper, and hail.

[on the outside]

To Sulpicia Lepidina (wife) of Glavius Cerialis; from Severa.

Other fortifications along the frontier consist of regularly spaced forts, similar to Vindolanda, about every 6 kilometres, supported by small fortlets and watchtowers. These do not seem to have been intended to serve as a linear defence but simply to protect the highway between Carlisle and Corbridge. There is no evidence of contemporary fortifications to the west of the former or to the east of the latter.

Hadrian

Publius Aelius Hadrianus (AD 117-138) was another Spaniard and a relative by marriage of Trajan. Hadrian too was a military man but he gave up the expansionist policies of his predecessor and abandoned his conquests in the East. After nearly 500 years of continuous expansion, the emphasis now shifted to the defence of the Empire. The result was nearly a century of peace and prosperity throughout the Roman World. The emperor himself undertook protracted tours of inspection leading to reforms of both the civil and military organization of the provinces.

Publius Aelius Hadrianus (AD 117-138) was another Spaniard and a relative by marriage of Trajan. Hadrian too was a military man but he gave up the expansionist policies of his predecessor and abandoned his conquests in the East. After nearly 500 years of continuous expansion, the emphasis now shifted to the defence of the Empire. The result was nearly a century of peace and prosperity throughout the Roman World. The emperor himself undertook protracted tours of inspection leading to reforms of both the civil and military organization of the provinces.

Britain, which had proved rather troublesome and was still not completely subdued, received an imperial visit in AD 122. The problem of the northern frontier had remained unresolved and there is some evidence to suggest Roman setbacks in the region. He appointed Aulus Platorius Nepos, his close friend, as the new governor. But with only three legions available— Legio II Augusta, Legio VI Victrix and Legio XX Valeria Victrix— it was decided that it was impossible to control all of Scotland and still garrison Wales and the Pennines.

The decision was made to establish a continuous curtain wall from the mouth of the Tyne to Solway Firth. The choice of this line (rather than the much shorter Forth-Clyde line) was presumably dictated by the need to provide support should trouble break out further south.