Vercovicium

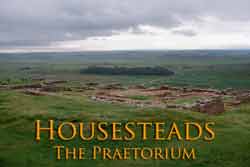

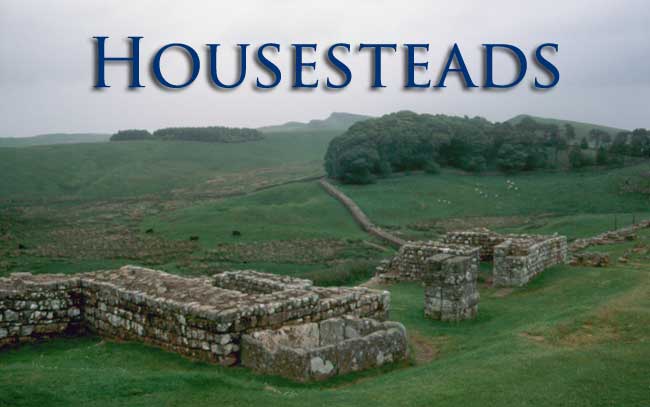

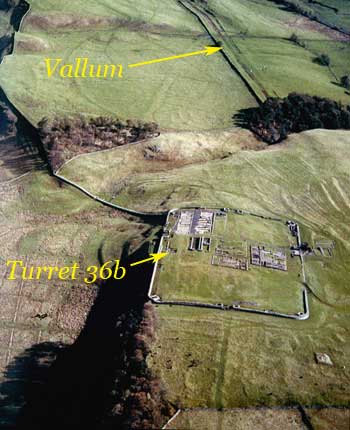

Because of its position on the Whin Sill ridge, Housesteads (ancient Vercovicium) is one of the better-preserved on the Wall. It was located by a major gap in the ridge, the Knag Burn (see photo) which also provided a reliable source of water. There had been a turret (36B) on the site immediately before the construction of the fort but this was immediately dismantled. Vindolanda, which it presumably replaced, was only some 3 kilometres away. The site is an awkward one with high ground to the west and a pronounced slope to the south. The Wall runs along the edge of the ridge and there was no room to build the fort astride it. Instead, the Romans were forced to simply attach it to the south face so that only one of its gates opened to the north.

Among the advantages of the location was the fact that there was a more than adequate supply of building materials within a few kilometres of the site-sandstone for the blocks and limestone for mortar. The remains of a number of old quarries and Roman lime kilns have been found in the immediate vicinity of the fort.

The actual Roman name of the site is arguable. Borcovicium or Borcovicus occurs in the Notitia Dignitatum, a fifth century document listing all Roman outposts in Britain, which places it between Brocolitia (Carrawburgh) and Vindolanda. However, another, much later document, the Ravenna Cosmology (seventh century) document, names a place called Velurtion. Whereas a dedicatory inscription actually found on the site suggests the name probably began VER— hence, Vercovicium. The exact meaning of the name is uncertain too. It may derive from a Celtic term meaning “the hilly place”or “the place of the effective fighters” but we cannot be sure.

The fort covers some 2 hectares (ca. 180 x 110 metres) and was probably built by members of the Legio II Augusta. After the refurbishment of the fort in ca. AD200, it was garrisoned by an auxiliary cohort, the Cohors I Tungrorum, from Belgica, but it is not known if they were present earlier.

The Defences

The stone ramparts were very narrow (1.3 metres) but they were backed by an earthen embankment held in place by a retaining wall six or so metres away. This to provide access to the top and create a reasonable fighting platform for the defenders. Like the Wall, they were made of stone blocks bonded with lime mortar and set into a rubble core. The quarry for the sandstone blocks lay only a few hundred metres away and there was a lime-kiln nearby to produce the mortar. The remains of a set of stairs in the southeast corner, of which four courses survive, suggest the walls were just over 4 metres high.

The stone ramparts were very narrow (1.3 metres) but they were backed by an earthen embankment held in place by a retaining wall six or so metres away. This to provide access to the top and create a reasonable fighting platform for the defenders. Like the Wall, they were made of stone blocks bonded with lime mortar and set into a rubble core. The quarry for the sandstone blocks lay only a few hundred metres away and there was a lime-kiln nearby to produce the mortar. The remains of a set of stairs in the southeast corner, of which four courses survive, suggest the walls were just over 4 metres high.

There were four gateways, set between flanking towers, on each of the four sides—those on the east and west sides were offset slightly north of centre while those on the long walls were well to the east. Each of them consisted of a pair of arched portals, supported by central piers at the front and the rear, and was flanked by a pair of towers containing guard rooms. Fragments of architectural decoration show that a windowed gallery ran above the arches, although how it was roofed is conjectural. Roofing tiles have been found at some gates but these could belong to later modifications. At Housesteads, the gates were recessed slightly from the face of the ramparts and each was secured by two sets of double doors.

Housesteads. The East Gate

The East Gate, the Porta Praetorium, was the main entrance to the fort and led directly to the headquarters building. A broken relief figure of the Roman goddess Victoria, was found just inside the gate, probably one of a pair of divine figures set in niches above it. The South Gate (Porta Principalis Dextra) and the North Gate (Porta Principalis sinistra) were used by troops and others seeking to pass through the fort and the Wall. The West Gate, the Porta Decumana, was where the supply wagons arrived on their way to the granary and workshops. Those with business in the fort would arrive and state their business or present their credentials to the sentry at the gate. Then they would either proceed or be conducted to one of the guard rooms in the flanking tower while their bona fides were checked.

GoogleEarth View of Housesteads

There were turrets at the corners of the fort with doorways at ground level but it is debatable whether or not there were staircases leading up to the ramparts since ovens filled up most of the ground floor in at least two of them. A drain ran through the ramparts from the northeast tower, presumably for a latrine. When the fort was built, there were only two interval towers, one on each of the long walls to the west of the gates. The others that appear on the plan were not added until the fourth century when the Picts became a threat to Roman security. The turrets, like those on the Wall, were probably about 10 metres high, rising a storey or two above the parapet walk at the top of the ramparts. Their original appearance is difficult to reconstruct due to later modifications but the best evidence suggests that there was a crenellated parapet wall at the top.

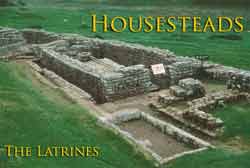

In addition to the ones in the corner towers, bakehouses were located in buildings just inside the ramparts and within the earthen embankment—well away from the wooden, thatch-roofed barracks. The rule seems to be one oven for each barrack block. There were a number of water-tanks set into the base of the rampart and in line with the retaining wall. They were lined with stone slabs caulked with lead and sealed at the bottom by a waterproof mortar. Some of them were placed against the rear walls of towers where they presumably caught rainwater channelled off the roof while others apparently collected water that ran off the paved roads. If the rainfall was insufficient, they could be topped up by trips to the nearby burn. The two largest cisterns were in the northeast corner and held 2,340 and 2,562 litres respectively.

The Buildings

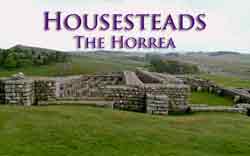

Running around the inside of the defences was a strip kept clear of buildings known as the via sagularis (literally 'cloak street' but it also was a military term for an assembly point). Within it were all of the principal buildings of the fort. The central block, at the intersection of the via principalis and the via praetoria, contained all of the administrative buildings. These are described more fully in the links below.

The Bath House

As was the case at most forts, the baths at Housesteads were located outside the fort—in this case some 200 metres to the east, beside Knag Burn. There were a number of good reasons for this. In the first place, space was at a premium within the fort; secondly, the furnaces to heat the building and the water represented a serious fire hazard; and finally, they required a lot of water so building them by a stream or river made good sense. The bathhouse at Housesteads are badly preserved but those at Vindolanda and Chesters give a good idea of their layout and appearance.