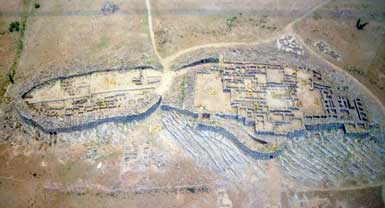

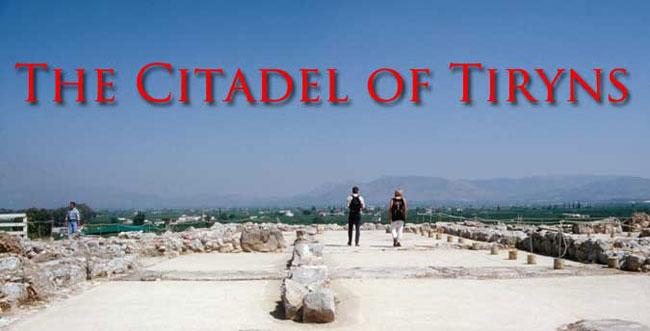

Tiryns.View of the surrounding countryside

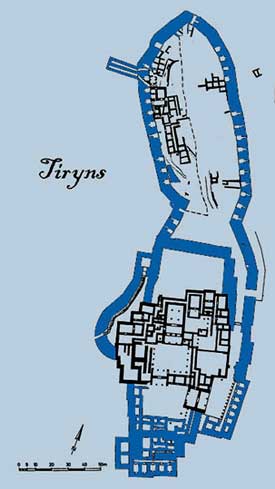

The site may well have been subordinate to Mycenae a few miles to the north, guarding the approaches from the sea which was a mere 100 metres away in the Bronze Age. It had been occupied as early as the Neolithic although, because of later building activity, little has survived from that period apart from a few potsherds. The earliest structures belong to  the Early Helladic II period (mid-3rd millennium BC). Substantial houses have been found all over the site, including the slopes of the hill, but the central feature was a large circular building about 28 metres in diameter which sat at the summit of the hill (underlying the later palace). It consists of a central space about 12.2 metres in diameter surrounded by concentric brick walls (see plan left) with radiating walls running from the centre to the periphery. The walls are substantial and indicative of a tall structure— although its precise function is unknown. It may be a shrine or some sort of mortuary building or merely a watchtower. Occupation continued into the Middle Helladic (the first half of the 2nd millennium BC)— although there may have been an hiatus between the two periods. Houses were arranged on a series of terraces which had been created by cutting and filling the surface of the hill.

the Early Helladic II period (mid-3rd millennium BC). Substantial houses have been found all over the site, including the slopes of the hill, but the central feature was a large circular building about 28 metres in diameter which sat at the summit of the hill (underlying the later palace). It consists of a central space about 12.2 metres in diameter surrounded by concentric brick walls (see plan left) with radiating walls running from the centre to the periphery. The walls are substantial and indicative of a tall structure— although its precise function is unknown. It may be a shrine or some sort of mortuary building or merely a watchtower. Occupation continued into the Middle Helladic (the first half of the 2nd millennium BC)— although there may have been an hiatus between the two periods. Houses were arranged on a series of terraces which had been created by cutting and filling the surface of the hill.

The Late Helladic period (1600-1100 BC) saw the site reach new heights of splendour with the construction of the palace and its immense walls (later Greeks believed that they must have been built by the Cyclopes). The earliest surviving remains of this period found on the site date to the 14th century BC but it underwent major renovations during this following years. The fortifications were enlarged and extended on at least two occasions and, although the bulk of the remains date to the late 13th century, there is clear evidence that there had been previous palaces on the summit. Architectural elements belonging to its immediate predecessor were incorporated into the latest version and fresco fragments from an even earlier building were found in the fill.

The Fortifications

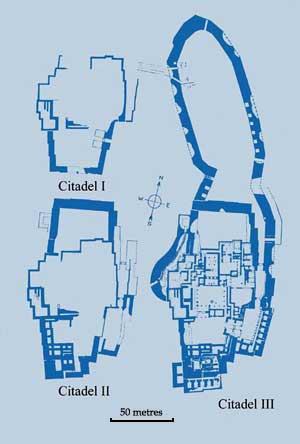

The walls were built in 3 phases and were gradually extended until they included the entire hill. The earliest version was erected early in the 14th century BC and enclosed the higher, southern part of the hill. It followed a somewhat irregular course to take in a roughly quadrangular area measuring roughly 75 x 125 metres. The main gate was on the east side, underlying what was to become the propylon, the outer entrance of the later palace. Unfortunately, the exact layout of the interior is unknown owing to the damage done by all of the later construction in the area.

These fortifications were expanded at some time around 1300 BC. A large bastion was built at the southern end of the citadel, where it was most vulnerable. A small doorway in the outer wall gave access to a stairway which led up to the interior of the citadel. The ramparts were also extended to the east, to enclose the area in front of the former gate and a new entrance was created at the north end of the small courtyard thus created. Later on, the gate was apparently moved further to the north and was protected by new walls which flanked it and extended beyond it to create a sort of corridor. A similar arrangement is found at the Lion Gate at Mycenae (see below). It seems highly probable that the so-called Middle Citadel to the north was fortified at about the same time.

These fortifications were expanded at some time around 1300 BC. A large bastion was built at the southern end of the citadel, where it was most vulnerable. A small doorway in the outer wall gave access to a stairway which led up to the interior of the citadel. The ramparts were also extended to the east, to enclose the area in front of the former gate and a new entrance was created at the north end of the small courtyard thus created. Later on, the gate was apparently moved further to the north and was protected by new walls which flanked it and extended beyond it to create a sort of corridor. A similar arrangement is found at the Lion Gate at Mycenae (see below). It seems highly probable that the so-called Middle Citadel to the north was fortified at about the same time.

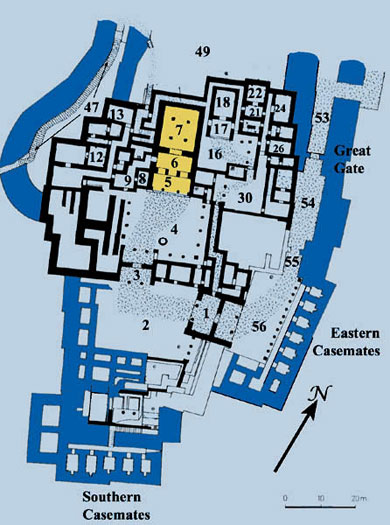

The third phase of construction, which took place in the latter part of the 13th century BC, saw the fortifications reach their final form. Two sets of galleries were attached to the southern and eastern side of the walls, each consisting of a passageway with a number of rooms opening off it— six on the east and five on the south. They were all constructed using the corbelling technique, where each course of stonework overlaps the one below it to form a pointed vault. These blocks were meant to support an extension of the terraces above. The corbelling technique allowed the builders to economize on stone while creating some useful storage space in the bargain. On the western side of the hill, a curving bastion was built to protect a winding stairway which led to a small postern  gate. The defenses on that side were further strengthened by the addition of a tower in the southwest corner. The lower terrace of the hill, running to the north, was fortified during this period, effectively doubling the area of the site. The new walls were massive, nearly 7 metres thick, and contained a number of ‘casemates’ (chambers built into the thickness of the wall). A couple of long tunnels ran beneath the walls on the western side to underground springs in the fields beyond. The main entrance was still on the eastern side of the fortress, at the end of a long ramp running parallel to the new ramparts. The gate opened onto a corridor (50) which also ran parallel to the walls, leading north to the lower citadel and south to the palace. At the southern end of the passage was the so-called ‘Great Gate’ (53: left) and beyond that, a covered corridor (54) which led to a double doorway (55). These represent the successive entrances of the previous phase at the site.

gate. The defenses on that side were further strengthened by the addition of a tower in the southwest corner. The lower terrace of the hill, running to the north, was fortified during this period, effectively doubling the area of the site. The new walls were massive, nearly 7 metres thick, and contained a number of ‘casemates’ (chambers built into the thickness of the wall). A couple of long tunnels ran beneath the walls on the western side to underground springs in the fields beyond. The main entrance was still on the eastern side of the fortress, at the end of a long ramp running parallel to the new ramparts. The gate opened onto a corridor (50) which also ran parallel to the walls, leading north to the lower citadel and south to the palace. At the southern end of the passage was the so-called ‘Great Gate’ (53: left) and beyond that, a covered corridor (54) which led to a double doorway (55). These represent the successive entrances of the previous phase at the site.

The Palace

At the end of the series of passages and gates was a trapezoidal courtyard (56) dating to the second phase of the fortress. During the final phase a colonnade was built along its eastern side, supported by the galleries below. The latter could be reached by a stairway leading from the south side of the courtyard. On the east side was the Great Propylon (1), the monumental entrance to the palace proper. Typically, it is laid out in the shape of a capital ‘H’ with porches on either side of the doorway. In this case, the porch roofs are supported by pairs of columns rather than single ones as at Pylos. A door in the north wall of the western porch leads to the east wing of the palace.

Beyond the Great Propylon is the outer courtyard (2) of the palace which occupied all of the southern part of the upper citadel. Unfortunately, the area was largely eroded and its restoration is somewhat conjectural. There were probably porticoes along the eastern and western sides and rows of rooms behind them. A second, smaller propylon (3) was located on the northern side leading to the Central Court (4) of the palace. To the east of the gateway was a small rectangular building with three rooms, each of which opened into the outer courtyard. These have been variously interpreted as guard rooms, archive rooms, workshops or simply store rooms. The Central Court was bounded by porticoes on three sides, on the south, east and west. Essentially this was a gathering place for people to observe the religious ceremonies which focused on the circular altar in the southern half of the court.

The ‘throne room’ suite, the Great Megaron (5-7), is virtually identical to that at Pylos, a megaron consisting of a portico with two columns, a broad antechamber and the throne room itself. The principal difference lies in the fact that here there are three doorways instead of one between the portico and the antechamber. The main room has the typical setting of four columns (the hearth has not been preserved) and there was a throne base up against the east wall. The floor was plastered and, as at Pylos, decorated with painted squares— in this case depicting octopuses and dolphins.

The West Wing of the palace (8-14) is only accessible from the Central Court, through a doorway in the north-eastern corner. Most of the southern part of the wing has been destroyed but the area next to the megaron includes a couple of residential units (12a and 13/13a) along with the so-called Bathroom (11). The floor of the latter is a single large slab of limestone which slopes slightly to drain the water away. There is a row of holes arranged in pairs around the perimeter of the room, presumably to support a waterproof dado running along the walls. The surplus  water drained into an adjacent light well (10) and from there to the main drainage system of the palace. The combination of Bath and light well suggests the room was used for cult purposes rather than mere personal hygiene. Further north is a stairwell (10a & b) leading to the upper storey of the palace. Finally, a corridor (15) runs around the back of the Throne Room Suite to the East Wing.

water drained into an adjacent light well (10) and from there to the main drainage system of the palace. The combination of Bath and light well suggests the room was used for cult purposes rather than mere personal hygiene. Further north is a stairwell (10a & b) leading to the upper storey of the palace. Finally, a corridor (15) runs around the back of the Throne Room Suite to the East Wing.

The main feature of the East Wing is the Small Megaron (17-18). It is about half the size of the Throne Room Suite and differs from it in that there is no antechamber and the hearth in the main room is rectangular rather than round. Its function is unknown but the usual interpretation is that it was for the use of the queen. To the south is a small forecourt (16) while to the east is suite of rooms, some of which had been decorated with painted plaster floors depicting dolphins and octopuses.

To the northwest of the Great Megaron was a stairway which led down some 2 metres to the Middle Terrace (49) of the citadel. It is enclosed on three sides by the thick ramparts of the second phase of construction. It is not entirely clear what function of this  space was because it has barely been scratched by excavation but the remains of a pottery kiln suggest it may have been used for workshops. To the west was a curved extension of the third phase ramparts which protected a long staircase (47) which led to a postern gate running through the wall to the outside. The entrance to the stairway was further protected by a square tower (48).

space was because it has barely been scratched by excavation but the remains of a pottery kiln suggest it may have been used for workshops. To the west was a curved extension of the third phase ramparts which protected a long staircase (47) which led to a postern gate running through the wall to the outside. The entrance to the stairway was further protected by a square tower (48).

The Lower Terrace

The Lower Terrace, the long spur running north from the palace, was first fortified at the beginning of the 13th century BC when it was enclosed by a huge wall some 7 metres thick. Until fairly recently the area had never been properly explored and was generally assumed to have been devoid of buildings. It was thought that it designed to be used as a refuge for the villagers who lived in the surrounding countryside. However, restoration work in the 1960’s led to systematic excavations in the area which have revealed that the area was in fact crowded with buildings.

The structures were laid out along laneways running north-south and included workshops as well as residential units. The terrace was accessible from the main gate by turning right and following the passageway. There were also smaller gates in the southwest and north which led directly into the area. The buildings were all destroyed in a particularly severe earthquake around 1200 BC. Thereafter, the site was occupied by a scatter of smaller houses until occupation ceased at the end of the Bronze Age about 150 years later.