The House of Atreus

Homer tells us that the most powerful king among the Greeks at Troy was Agamemnon who ruled from his mighty fortress at Mycenae, “rich in gold.” The story of Agamemnon and how he came to be king is convoluted, to say the least, so you are really going to have to pay attention. There is plenty of sex and violence.

story of Agamemnon and how he came to be king is convoluted, to say the least, so you are really going to have to pay attention. There is plenty of sex and violence.

According to legend, the great citadel was built by the hero Perseus, prince of Argos and slayer of the Gorgon Medusa, who enlisted the help of the Cyclops to build its massive stone ramparts. For that reason this type of masory is known as ‘cyclopean’ (left). The Perseid dynasty came to an end with the death of Perseus’ grandson in battle. Leaderless, the Mycenaeans chose Atreus, son of Pelops as their new king.

Pelops was king of Pisa, in the northwest Peloponnese (the “Iland of Pelopts”). He acquired the throne by cheating his way to victory in a chariot race with the previous king, Oenomaus. Oenomaus had a daughter, Hippodameia, whom Pelops wanted as his wife (the couple are shown in the jar fragment, below right) but it had been prophesied that the king would die at the hands of his son-in-law. He had already killed no less than thirteen previous suitors whose driving skills were not up to scratch—their severed heads were nailed to the columns of his palace. Needless to say, Pelops was somewhat concerned that this fate awaited him too and so he cooked up a scheme with the king’s groom, Myrtilus, to remove the bronze lynchpins that held the wheels in place and replace them with wax versions. The deal was that the groom would be rewarded with half the kingdom  and one privilege of sharing Hippodameia’s bed on her wedding night. The plot was a success and Oenomaus was killed in the resulting chariot crash, but Pelops had no intention of honouring his side of the bargain. Hippodameia cried “Rape!” and Pelops kicked him off a cliff—but not before he cursed Pelops and all his descendants. It was to commemorate these events that the Olympic Games were instituted, so don’t go moaning about what has happened to Olympic ideals.

and one privilege of sharing Hippodameia’s bed on her wedding night. The plot was a success and Oenomaus was killed in the resulting chariot crash, but Pelops had no intention of honouring his side of the bargain. Hippodameia cried “Rape!” and Pelops kicked him off a cliff—but not before he cursed Pelops and all his descendants. It was to commemorate these events that the Olympic Games were instituted, so don’t go moaning about what has happened to Olympic ideals.

Pelops had two sons by Hippodameia, Atreus (the elder) and Thyestes, but he had another, his favourite, a bastard by the name of Chrysippus. Fearing that they would be set aside by their father and encouraged by their mother, the two brothers murdered Chrysippus and tossed him in a well—the curse has begun its work. Banished along with their mother from the kingdom, the two brothers were given refuge by Eurystheus, the aforementioned grandson of Perseus (and the king who set the Twelve Labours of Herakles). The selection of his brother rankled with Thyestes, for the two were bitter rivals, and he was not content to play second fiddle. The first thing he did was seduce his sister-in-law, Aerope. From her he learned about a golden-fleeced lamb among her husband’s flocks that had been promised by him as an offering to Artemis, the goddess of wildlife. However, instead of giving her the whole animal, he kept the fleece, mounted and stuffed, for himself. Aerope stole it and handed it over to her lover. At a council meeting Thyestes tricked Atreus into claiming that he had the right to sit on the throne through its possession. At that point, Thyestes took the councillors to his house and to the amazement of all, produced the fleece. Atreus had no choice but to resign in his favour. However, Zeus was not happy with the way events unfolded and tricked Thyestes to hand the throne back by causing the sun to reverse directions.

Despite the fact that Thyestes’ plot turned out to be a failure, Atreus was seething with thoughts of vengeance. He invited his brother to a conciliatory feast and served him up with some choice pieces of meat. After asking him how he enjoyed dinner, Atreus revealed that it was his own infant sons that he had eaten. Thyestes ran off distraught and horrified, cursing his brother and vowing revenge. The first thing he did was consult the oracle at Delphi, which told him that the instrument of his vengeance would be the son he would beget on his own daughter, Pelopia. So he went to Sicyon, where his daughter served as a priestess to the goddess Athena, to do the will of the gods. One night, after sacrificing  to the goddess, the girl splattered some of the blood on her tunic and slipped it off to wash it in the temple pool. Thyestes, who had been lurking nearby, sprang from the bushes and raped her. He was wearing a mask, so she had no idea who he was but she did manage to steal his sword. As the example (left) from one of the graves at Mycenae shows, these can be quite distinctive.

to the goddess, the girl splattered some of the blood on her tunic and slipped it off to wash it in the temple pool. Thyestes, who had been lurking nearby, sprang from the bushes and raped her. He was wearing a mask, so she had no idea who he was but she did manage to steal his sword. As the example (left) from one of the graves at Mycenae shows, these can be quite distinctive.

Meanwhile, Atreus had been advised by the same priests at Delphi to patch things up with his brother and was on his way to Sicyon, keen to let bygones be bygones. But, by the time he arrived, Thyestes had discovered that his sword was missing and, fearing his cover was blown, had already left town. His journey wasn’t entirely wasted, however. Having put his unfaithful wife to death, he was in the market for a new queen and Pelopia was the best thing he had seen all day. Blissfully unaware that she was his niece, he fell hopelessly in love and promptly married her. The fact that she was now pregnant made things a bit awkward so, when a baby son was born, she left him on the hillside to die. Fortunately for him, he was picked up by some goatherds who happened to be passing. They gave him to a she-goat to suckle and so he came to be called Aegisthos (“goat strength”). Atreus firmly believed that the child was his and that his bride was temporarily unhinged due to postpartum depression. He took Aegisthos into his palace and raised him with his other two sons, Agamemnon and Menelaos—the ones whose mother he had recently killed.

Seven years later, who should show up but Thyestes. He was promptly thrown in prison and Atreus ordered young Aegisthos to kill him. But the boy was not up to the duty. Thyestes easily kicked the blade out of his hand and was astonished to discover that it was the same sword that he had lost all those years ago. When he asks him how he came by it, the boy replies that his mother had given it to him. Thyestes then ordered him to bring his mother to the prison and there is a  tearful family reunion. But then the truth comes out. Overcome by the shocking truth, Pelopia grabbed the sword and plunged it into her breast. Shrugging this unfortunate occurrence aside, Thyestes then told the boy to take the sword, dripping with his mother’s blood, show it to Atreus and tell him he has carried out his duty. Atreus is overjoyed and offered up a sacrifice to Zeus, believing that all of his troubles were behind him. Only then did Thyestes order his son to kill him and so finally realize his life’s ambition to sit on his brother’s throne.

tearful family reunion. But then the truth comes out. Overcome by the shocking truth, Pelopia grabbed the sword and plunged it into her breast. Shrugging this unfortunate occurrence aside, Thyestes then told the boy to take the sword, dripping with his mother’s blood, show it to Atreus and tell him he has carried out his duty. Atreus is overjoyed and offered up a sacrifice to Zeus, believing that all of his troubles were behind him. Only then did Thyestes order his son to kill him and so finally realize his life’s ambition to sit on his brother’s throne.

Atreus’ other two sons, Agamemnon and Menelaos, were forced to flee the palace eventually ending up in Sparta where they were given sanctuary by its king, Tyndareos. Tyndareos was blessed with two daughters, Klytemnestra and the beautiful Helen. Helen’s eye-popping beauty was due to the fact that her real father was the god Zeus. Having killed his own father and seduced or raped every woman or goddess that took his fancy, Zeus was the perfect role model for the sons of Pelops. In this particular instance he came to Tyndareos’ wife, Leda, in the form of a swan. Nine months later Leda laid a pair of eggs. Out of one came Helen and her brother, Pollux, while out of the other (this one fertilized by the king) came Klytemnestra and Castor.

After expelling Aegisthos and restoring Agamemnon, the rightful heir to the throne of Mycenae, Tyndareos gave his daughters in marriage to the brothers. All of the leading lights of the Greek World wanted to marry Helen—the Athenian hero, Theseus, went so far as to kidnap her when she was a mere child—but in the end Tyndareos chose Menelaos. Agamemnon’s bride, Klytemnestra, was not quite so willing. She already had a husband, Tantalus the ruler of Pisa in the northwest Peloponnese. As you may remember, Pelops, Agamemnon’s grandfather had once been king there and this Tantalus was the old king’s nephew and therefore some sort of cousin to Agamemnon. That did not stop him from murdering him, however. As for Klytemnestra, after watching her infant son slaughtered before her eyes she was raped by the triumphant Agamemnon.

It was the seduction (or rape, depending on whose version of events you believe) of Helen by Paris and their subsequent elopement (or abduction) that brought about the Trojan War. Agamemnon  swore to recover his brother’s wife and commanded all of the Achaean warlords to gather with their ships and men at Aulis on the Boeotian coast opposite the island of Euboea. At Aulis, the fleet was held up by contrary winds—thanks to the goddess Artemis whom Agamemnon had offended by killing one of her sacred deer. Apparently the only way to appease the goddess was for the king to sacrifice his eldest daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess. Agamemnon was reluctant at first but, when the rest of the Greeks threatened to appoint another commander, he relented. Having told Klytemnestra that her daughter was to be married to Achilles, he persuaded her to bring the girl to Aulis where she was offered up to the goddess, no doubt reinforcing the already strong marital bonds between them.

swore to recover his brother’s wife and commanded all of the Achaean warlords to gather with their ships and men at Aulis on the Boeotian coast opposite the island of Euboea. At Aulis, the fleet was held up by contrary winds—thanks to the goddess Artemis whom Agamemnon had offended by killing one of her sacred deer. Apparently the only way to appease the goddess was for the king to sacrifice his eldest daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess. Agamemnon was reluctant at first but, when the rest of the Greeks threatened to appoint another commander, he relented. Having told Klytemnestra that her daughter was to be married to Achilles, he persuaded her to bring the girl to Aulis where she was offered up to the goddess, no doubt reinforcing the already strong marital bonds between them.

Then, having murdered her first husband and their baby, raped her and finally slaughtered their daughter on the altar of politics, Agamemnon then disappeared for ten years. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Klytemnestra was susceptible to the advances of Aegisthos (remember him?) who has decided to sit out the Trojan War and seek his revenge on the House of Atreus. When Agamemnon finally returned, the two decided to do him in. Any doubts Klytemnestra may have had—and I suspect they were minor at this point—were quickly resolved by the presence of Cassandra, former princess of Troy, current trophy-wife, and the mother of Agamemnon’s twin sons. Klytemnestra greeted her long-lost husband with every appearance of delight and suggested he retire to the bath house for a nice long soak. Just as the king stepped out of the tub, Klytemnestra threw some sort of net over his head while Aegisthos stabbed him to death. Seizing an axe, she then chopped off her husband’s head and ran outside to deal the same fate to Cassandra who, being a prophetess, was not surprised in the slightest.

According to Robert Graves, the peculiar manner of Agamemnon’s death—neither naked nor clothed (the net), neither in the water nor on dry land, neither in the palace nor outside it—is the same sort of death meted out to the sacred king who is sacrificed at midsummer in a number of Indo-European myths including the Welsh epic, the Mabinogion. In fact, Graves believes the whole cycle of stories has to do with the (violent) transition from a matriarchal to a patriarchal society that takes place with the arrival of Greek-speakers into the peninsula.

with the (violent) transition from a matriarchal to a patriarchal society that takes place with the arrival of Greek-speakers into the peninsula.

Whatever Klytemnestra’s motives, Aegisthos’ plan was to exterminate the line of Atreus and that meant that Orestes, her son by Agamemnon had to go too. Fortunately for him, the boy was spirited out of the palace (either by his nurse or by his sister, Elektra, according to which story you believe). After eight years exile in Athens he returns in secret to exact revenge for his father’s murder, which he does in typically bloody fashion. For the crime of matricide Orestes is hounded by the Erinýes (Furies) and driven insane (right). In Aeschylus’ play The Eumenides Orestes is brought to trial in Athens and cleansed of his blood guilt, thus establishing the ultimate authority of human institutions.

The Site

When Schliemann began his investigation of Mycenae in the 1870’s he found that the ancient description, “rich in gold,” was no exaggeration. Subsequent excavations, chiefly by Christos Tsountas, Alan Wace and George Mylonas, have only confirmed this.

The site is located in the northwest corner of the Plain of Argos, in the shadows of Mount Prophet Elias and Mount Zara and dominates the plain and the overland routes from the southern Peloponnese to the Isthmus of Corinth and the rest of Mainland Greece. Through its dependencies at Tiryns and Argos it was well-connected with Cyclades and the larger Mediterranean World— Egypt, Crete, Syria and Canaan.

View of the Citadel at Mycenae from the south

The citadel was located at the top of a fairly steep, highly defensible hill which dominates the surrounding plain. There were apparently several small villages scattered in the hills around it— often their locations are only indicated by the rock-cut tombs nearby. There is no dense build-up of occupation normally associated with a city. The picture is more like that of a medieval castle surrounded by small hamlets and isolated farmsteads.

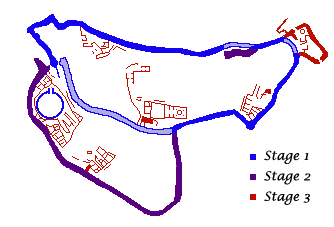

The earliest remains on the hill date to the 14th century BC when the summit was first fortified. Unfortunately, these (and subsequent building activity) have destroyed any trace of earlier occupation. However, the presence nearby of Middle Helladic cemeteries and even earlier material point to a long occupation, perhaps beginning in the third millennium BC. In the 13th century, two subsequent extensions of the original ramparts brought a large part of the southern slope, including the existing cemetery known as Grave Circle A, within their protection. At its greatest extent, the site only covered some 3 hectares.