The Life and Times of Pa-ramessu

Pa-ramessu means “the sun god Re has fashioned him”. It is a late New Kingdom version of the name Ramesses. The fairly common name, sometimes written as Ramose in English, shows an orthodox devotion to the Sun God Re, pre-eminent deity the Egyptian pantheon.

Pa-ramessu means “the sun god Re has fashioned him”. It is a late New Kingdom version of the name Ramesses. The fairly common name, sometimes written as Ramose in English, shows an orthodox devotion to the Sun God Re, pre-eminent deity the Egyptian pantheon.

Pa-ramessu (right) was probably born around 1350 BC, in the last years of Amenhotep III, at the height of the glory of the Eighteenth Dynasty. He was the son of a troop commander named Seti. The family lived in the northeast Delta of Egypt, near Avaris. Four hundred years before, Avaris had been

The common family name Seti, “man of Seth”, honours Seth or Sutekh, god of the powerful forces of desert, storm, battle, and chaos who was honoured at Avaris. Commander Seti was career military man who may not have seen much fighting under Amenhotep III, who preferred diplomacy to war. Nevertheless, he rose to be commander of the border fortress of Sile, close to the modern Suez Canal. Though a lack of battles may have limited opportunities for advancement, the army was not idle during Amenhotep III's reign. Egyptian influence and power extended for over two thousand miles, from the Euphrates in the North, eight hundred miles south into Nubia as far as the Third Cataract. Nubia had been integrated into the Egyptian empire. Great temples were built there. Egypt was enriched by gold from the mines and ivory, ebony and other exotic trade goods from central Africa. In the North, as Timothy Kendall has written, “Amenhotep III managed his Asian empire with diligence and skill. He corresponded frequently with his fractious vassals, kept them under closer scrutiny, appointed Egyptian governors, and quartered troops in the region.” The situation for military families and for all other Egyptians changed dramatically with the accession of Amenhotep III's successor, his son Amenhotep IV. Amenhotep IV is better known by the name he chose for himself, Akhenaten.

Paramessu grew up during tumultuous times. Though Akhenaten is now remembered chiefly for his religious ideas, and the style of art associated with his reign, later generations of Egyptians reviled his memory. He was called “the enemy of Akhet-Aten” and his reign was referred to as “the rebellion”. The revolution he sought to impose upon Egypt so destabilized the culture that Akhenaten and his entire family were erased from official history. After his death, his capital city was abandoned. Recycled blocks of his dismantled monuments filled structures built by the kings who came after him. His own tomb was  attacked and his burial desecrated, the sarcophagus smashed to pieces. His mummy was not carefully reburied with the other royal dead. Its fate is unknown. To understand Paramessu and his world, we must try to imagine what it was like to live during Akhenaten's seventeen-year reign and its aftermath. Ramesses' career as soldier, vizier, and finally pharaoh was in large measure a reaction against Akhenaten and everything associated with him.

attacked and his burial desecrated, the sarcophagus smashed to pieces. His mummy was not carefully reburied with the other royal dead. Its fate is unknown. To understand Paramessu and his world, we must try to imagine what it was like to live during Akhenaten's seventeen-year reign and its aftermath. Ramesses' career as soldier, vizier, and finally pharaoh was in large measure a reaction against Akhenaten and everything associated with him.

When Amenhotep IV/Akhenaten (left) assumed the throne, possibly in co-regency with his father, Egypt seemed to be in the state of harmony and good government known as Maat. Truth and justice were triumphant, evil was at bay. Pharaoh ruled from two residences or capitals, Memphis in the north and Thebes in the south. The young king began his rule by completing some of his father's work at the temple of Karnak in Thebes, and at Soleb far to the south in Nubia. He also began work on four new temples dedicated to his personal god, the Aten, visible disk of the sun. The Karnak buildings had many unusual features that provided dinner conversation for the man and woman in the Theban street. Though his earliest structures sometimes showed the king as a handsome, powerful warrior, Akhenaten had increasingly chosen to have himself represented in a manner that broke with traditions. In contrast to the athletic figure of most royal images, a series of colossal statues showed him with narrow shoulders, prominent breasts, wide hips, and a belly that overhung his belt. Were the androgynous images reflective of his actual appearance? Or was he attempting to show himself both male and female, father and mother of his country?

Whatever the thinking behind them, the huge statues required many man-hours to quarry, erect and decorate. Talatat, small blocks of stone easily carried by one man, accelerated construction of the new temples, and hearkened back to the size of blocks used over a thousand years before, in the enclosure wall of the Step Pyramid. Hundreds of men quarried stone, dug ditches and shifted sand. Artists in great numbers carved and painted scenes on walls while their children ground paints and fetched chisels and water. Women wove acres of linen for the ceremonies, and prepared bread and beer for the workers. Gardeners planned and planted in anticipation of an increase in revenue from the fruits and flowers required by the new liturgy. Everyone in Thebes, from architects to water boys would have been fully employed. People may have gossiped about the strange statues, or the king's uxorious relationship with his wife, Nefertiti, and her prominence in the temple's decoration, but the construction itself brought good times.

By Year Five, however, building activity had come to an end at Thebes and Memphis. Amenhotep (Amun is Satisfied) changed his name to Akhetaten (Useful to the Aten). In Year Six, the Royal Family set up a new Royal Residence, Akhetaten (the Horizon of the Aten) in Middle Egypt. When the king left, so did jobs. Some people voluntarily followed the king to the new site, now commonly known as Amarna. Some of the Nobility may have accompanied the king as their service to the state required, taking with them their households of servants, but in large measure, Akhenaten ignored the old families and chose as ministers men from obscure families, who would owe all prosperity and hope of advancement to himself. Thus, at a time when the king was planning an almost complete reorganization of Egyptian society—a revolution—the most experienced men were deliberately excluded from power and influence. Lower-ranking civil servants were required to leave their villages to travel north. The workers who carved and painted the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings were forced to relocate, far from their beloved mountains, shrines and the tombs of their ancestors. Ancient poets expressed this homesickness.

Behold, I do not want to depart from Thebes.

Save me from what I abhor!

Bring me to your city, Amen!

Because I love it;

it is your city that I love,

more than bread and beer, Amen,

more than clothes and oil,

I love the soil of your town

more than the ointment of another land.

Families with lands or careers tied to the temples in Thebes could not move. Abandoned by the royal court, Thebes became a poorer and less interesting city. Gradually at first, the great temples were starved for revenue as Akhenaten diverted the wealth of their estates into the service of the Aten. Eventually, the temples of Amun and the other gods were closed and their rites forbidden.

Akhenaten did not worship the pantheon of gods who had protected and enriched Egypt for millennia. His attention was only for the Aten The Aten, transcendent, omnipotent, omnipresent, was to be the only god worshipped in Egypt. But the Aten was a god without a mythology; there were no stories to tell of his history and deeds. Osiris, great hope of the people as the guarantor of immorality and ultimate justice, and his sister-wife Isis, the model of fidelity and motherhood, were simply ignored. Amun, the god of empire, and Montu, the soldier's support, were proscribed. Though people might attempt to preserve in secret their private devotion to Ptah or Hathor, or Seth, none of these deities received official offerings. Their temples were closed, their priesthoods dispersed. The Aten's principal temples were erected at Akhetaten, where offerings were presented by the king and queen. Though a new priesthood was established, and constructions begun in various towns, the common people, civil servants, soldiers, and nobles could not worship the Aten directly. Egyptians were to focus their prayers on the royal family. They would transmit the power and goodness of Aten to all.

History can show many examples of the difficulties people face when a new state religion is imposed upon them. Akhenaten's decision to outlaw the old gods of Egypt and to close their temples must have caused hardship and stress that was both psychic and economic. After his death, this time was remembered in the Restoration Stela of Tutankhamun as one of loneliness and confusion:

Now when His Majesty rose as king, the temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting at Elephantine [right down] to the marshes of the Delta…. [had fallen] into ruin. Their shrines were decayed, having become mounds of rubble, overgrown with weeds. Their sanctuaries were as though they had never existed. Their temples were a footpath. The earth was in calamity and the gods forsook this land…. If one prayed to a god in order to ask advice from him, he would not come at all. If one prayed to any goddess likewise, she would not come at all.

Now when His Majesty rose as king, the temples and the cities of the gods and goddesses, starting at Elephantine [right down] to the marshes of the Delta…. [had fallen] into ruin. Their shrines were decayed, having become mounds of rubble, overgrown with weeds. Their sanctuaries were as though they had never existed. Their temples were a footpath. The earth was in calamity and the gods forsook this land…. If one prayed to a god in order to ask advice from him, he would not come at all. If one prayed to any goddess likewise, she would not come at all.

It's difficult appreciate the central position of the temple in the Ancient Egyptian economy. The temples employed priests, watchmen, gardeners, weavers, bakers, butchers, singers and dancers, healers and teachers. Not only were great numbers of people directly employed by the temples, but thousands of other citizens received part of the offerings given to the gods when the ceremonies were over. The oxen slaughtered for the gods were not left to rot on the altars; after the gods had taken their share of the meat, the rest was divided up into portions for the priests, and for every one connected with the ceremonies. A single bull might provide high quality protein for hundreds of people. Major feasts gave even the poor a chance to eat meat, drink beer, and stuff themselves with bread and cakes. The floral offerings would revert to people who would carry these blessed bouquets to the graves of their own families. And finally, the feast days were holidays. In Thebes, every procession that carried the statue of the god Amun to Luxor Temple, or crossed the Nile to visit the goddess Hathor on the West Bank, injected excitement, entertainment, and colour into everyday life. The great processions united citizens in praying, singing, and feasting together. Akhenaten's obsession with the Aten put an end to all this.

Karnak. The Boat-Procession of Amun

The hardships caused by Akhenaten's revolution were probably most painful in Thebes, the city of Amun. How would Akhenaten's revolution have affected Paramessu, growing up in the Delta? Egypt under the radiance of the Aten still needed an army. In fact, images of soldiers abound in the talatat from the early buildings at Karnak as well as the later structures at Akhetaten. Officers organized and soldiers guarded the expeditions Akhenaten sent to Aswan to quarry granite, and to Gebel el-Silsileh for sandstone. The king had another use for the soldiers' familiarity with stone-working. Akhenaten used the army to enforce his religious revolution. Soldiers accompanied the gangs of workers who defaced the monuments of Amun, erasing his images and chiseling out his name (and often those of other gods) from temples as far south as Soleb in Nubia. If the image of deserted temples with empty sanctuaries in Tutankhamun's Restoration Stele is true, parties of armed men must have entered the temples and forced their way back into the most sacred and secret parts to destroy the statues that embodied the power of the gods. By the time the army was finished the work of destruction, “shrines were decayed, having become mounds of rubble, overgrown with weeds.” Even more distastefully, the chiselers entered private tomb chapels to erase the names of gods. This often meant erasing part of the name of an individual, leaving him without identity for all eternity. At Amarna itself, small privately owned objects have been found with the name of Amun erased. How would the people have reacted to this  misuse of the army? Royal power was not being used to uphold Maat, but to destroy.

misuse of the army? Royal power was not being used to uphold Maat, but to destroy.

The effect of the iconoclasm on the military who were ordered to undertake it cannot be overestimated. Military discipline requires good officers and well-trained soldiers, but also clear objectives and rules of conduct. Soldiers, even more than other men, rely on the gods' favour. A soldier who has desecrated a shrine has broken through a kind of psychic barrier, transgressing the most sacred precepts of his culture. Would such men be able to respect other laws? Or would parts of the army turn into gangs of thugs?

The Decree of Horemheb, issued fifteen or so years after Akhenaten's death, suggests that this was what happened:

If a private individual makes for himself a boat with its on-board shelter, in order to be able to serve Pharaoh, l.p.h. and if people of the army come and appropriate it as if it were for taxes: the individual is despoiled of his property and deprived of his abundant means of doing service. This is a crime!

Further, the two corps of the army, when they are in the field, . . . have been appropriating hides throughout the entire land, without ceasing for a single year…going from house to house, with beatings and duckings, not leaving a single hide.

The severity of the problem may be judged by the punishments ordained:

And as for any member of the army about whom it will be heard that he goes and still appropriates hides today, let the law be applied against him by beating him with one hundred blows and five open wounds, and by confiscating the hide he has taken by theft.

While part of the army was embroiled with internal affairs, those whose duties involved external enemies continued in a more traditional manner. Akhenaten was not a pacifist, and did not tolerate the defection of subject peoples. He commanded the Viceroy of Kush, Thutmose, to dispatch forces to deal with a rebellion in the district of Akita in Nubia. This minor war was dealt with very forcefully: only 145 Nubians and 361 cattle were captured, but an undisclosed number of the captives were impaled upon stakes. Although it is unlikely that Pa-ramessu or his father, Seti, would have been involved in Nubia, close relatives may have fought there. In the North, as part of the elite chariot-corps, members of the family would certainly have seen service in the field. The Amarna Letters, part of the archives of Akhenaten's 'Ministry of Foreign Affairs,' tell of confused times. King Tushratta of Mitanni, Egypt's ally, was battling the emerging Hittite empire. He appealed for assistance.

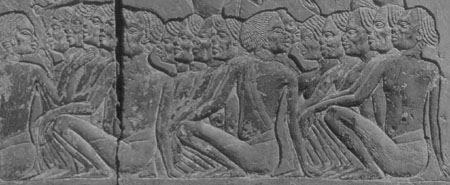

Sakkara.Tomb of Horemheb .Relief of Nubian Prisoners

Although talatat from Karnak show Egyptian soldiers engaging Hittite forces in Syria, and documents from the Hittite side, particularly the Annals of King Mursilis, describe Egyptian troop movements and battles, Akhenaten's response was insufficient to save Mitanni. Tutankhamun's Restoration Stele complains that,

If the army was sent to Djahy to widen the borders of Egypt, they would have no success.

Akhenaten had not led an army to intervene as Tuthmosis III or Amenhotep II would have done. Tushratta was eventually assassinated, and many small states in North Syria became allies of the Hittites. In the course of the struggle, the city of Kadesh on the Orontes, once a vassal of Egypt, was taken by the Hittites. Whatever losses Egypt sustained in influence and power as a result, military intelligence and courier networks continued to function. The King's lack of effective action in the crises in Syria-Palestine would have been known and discussed in Pa-ramessu's family. Pa-ramessu's son, Seti I, and grandson, Ramesses II, would each campaign in Syria to re-establish the balance of power, and fight, unsuccessfully, to regain control of Kadesh.

Another series of events may have profoundly affected young Pa-ramessu. Around Year 11 of Akhenaten, a plague swept through the Levant. The sickness affecting Byblos and other coastal cities spread to Egypt. Even the Royal Family, sequestered at Akhetaten, seems to have been affected, as attested by the many deaths of royal relatives. The king's second daughter, Meketaten, had died by Year Fourteen. Queen Mother Tiye disappears from the records about this time, as do the king's three youngest daughters. Some authors would add Nefertiti to the list. Seeing death around them, forbidden the rites of Osiris, would ordinary Egyptians have blamed the king? The plague goddess Sekhmet had been honoured by Amenhotep III with hundreds of statues. Was the pestilence her reaction to being ignored by his son? No god or goddess comforted the dying, nor answered the anguished prayers of parents and friends. For twenty years, the plague prevented effective military action by either the  Hittites or the Egyptians in Syria. Plague was a serious threat to health and life for the military families in the North. But by reducing the number of young officers, the plague may also have led to increased opportunities for survivors like Pa-ramessu.

Hittites or the Egyptians in Syria. Plague was a serious threat to health and life for the military families in the North. But by reducing the number of young officers, the plague may also have led to increased opportunities for survivors like Pa-ramessu.

Finally, after seventeen years on the throne, Akhenaten himself died. The immediate succession is not clear but within three years, a boy of nine or twelve had been crowned king of Egypt.

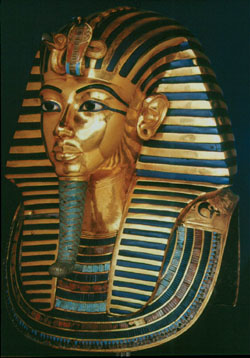

Tutankhamun (right) is now generally believed to have been Akhenaten's son by a secondary wife, Kiya. The boy was originally named Tut-ankh-Aten, which could be translated as “living image of the Aten”. Since Akhenaten was himself “the beautiful child of the sun god”, Tut's original name might be interpreted as chip off the old block. Within a few years, the boy-king and his court moved from Akhetaten to Memphis and began to reopen and refurbish the temples of Ptah, Amun, and the other gods. The Restoration Stele proclaimed that the kingdom had been misgoverned, and it would be the policy of the new king to set the country back on course, or, in Egyptian terms, to restore Maat. For a son to change his name to honour the god his father despised and displaced, abandon the city his father founded, and then overturn his father's policies would be evidence of a severe Oedipal conflict, if Tutankhamun himself had really been responsible. But little boys rarely have the intellect or will power to effect such changes. Who really ruled Egypt and wrote the edicts?

It had been traditional in Egypt for child-kings to have regents, usually their mothers, to rule in their names. Tutankhamun's presumed mother, Kiya, had died long before; his stepmother Nefertiti and his oldest sister Meritaten were presumably dead as well. Nefertiti's remaining daughter was his teen-aged half-sister, Ankhesenpa-aten. The girl's name was changed to Ankhesenamun and she became the boy's Great Royal Wife. Perhaps she was considered too young to be regent, or perhaps it was not considered seemly or wise for a wife to act as regent for her husband. The people who did hold power during Tutankhamun's nine year reign were two military men, Ay and Horemheb, each of whom assumed the throne in turn after the king's early death. Tutankhamun's Karnak Restoration Stele was written, and the actual restoration was planned and carried out by the military in what could best be described as a counter-revolution.

Voices of dissent from the years when Akhenaten reigned have not survived. The extent of the disruption caused by his policies can only be judged by texts written on the monuments of his successors. How reliable are these sources?

If the texts had been written in generalities, saying, as kings of Egypt traditionally did, that they had restored right, fought evil, extended the borders of Egypt and increased the wealth of the temples, there would be no reason to accept their implied descriptions of Akhenaten's regime. However, the Restoration Stela of Tutankhamun, Horemheb's Coronation and Restoration Decrees, and the Nauri Decree of Seti I (published more than forty years after Akhenaten's death), teem with references to specific instances of corruption, mismanagement and incompetent government. The examples already cited speak, for example, of weeds growing in the temple courtyards, and the sacred spaces becoming public pathways. Such details are something new in royal propaganda. Reports of military misconduct in the theft of boats and hides, of beating civilians, and taking bribes are not the kind of information that a government would publicize unless the abuses were so common and so flagrant that the warrior-kings were forced to acknowledge their truth, and then to pursue and punish the criminals. On the whole, we may accept the truth of the four documents. Enforcing the first three decrees, and inspiring the fourth, would be Pa-ramessu's role in Egyptian history.

Pa-ramessu received many promotions while Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun were growing up. He became Superintendent of Horses, a position that made him eligible to join the elite Royal Envoys. As such, he would have often visited the court in Memphis. His clear mind and physical energy brought him to the notice of his superiors. He began to learn the business of government, but there was no reason to suspect that he would ever achieve more than high military or civil office. If the young king and queen had been able to raise a family of their own, Pa-Ramessu would have scarcely made a mark on history, nor been noticed except by Egyptologists specializing in the New Kingdom. But the young couple had no living children.

At Memphis, the education and daily lives of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun had been directed by the God's Father Ay, a relative and himself a military man. Affairs of state were in the hands of Horemheb, Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Sole Friend and Royal Scribe. He also carried the titles of Iry-Pa't (an ancient title which seems to have meant Heir Apparent), Idenew (Deputy), and Nes Per Wer (Great Steward). The early death of the young king precipitated a crisis. Horemheb, the officially designated heir to the throne, should have succeeded in the absence of royal offspring. However, he may have been campaigning and 'out of the loop' on developments at the Residence. Ankhesenamun seems to have attempted a coup by writing to the king of the Hittites, asking for one of his sons to marry and establish as king of Egypt. After some hesitation on the part of the Hittites, prince Zananza set off, but the young man died or was killed on route. Horemheb, perhaps with the assistance of Pa-Ramessu (who by now may have succeeded his father as Commander of the border fortress of Sile,) may have forestalled the queen's treasonous plans, but they were unable to prevent usurpation.

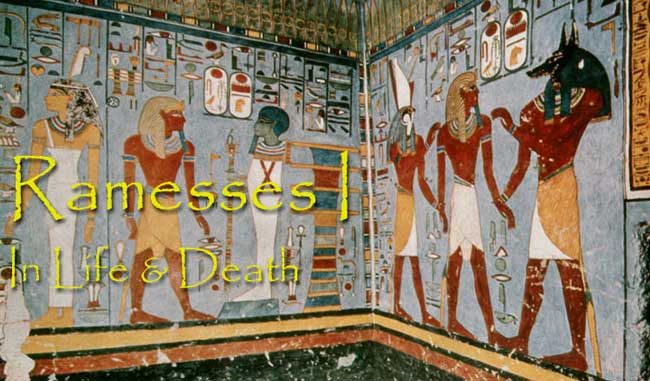

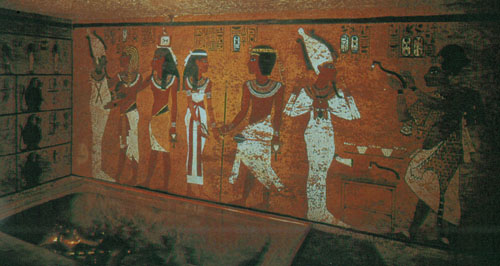

Tomb of Tutankhamun. Burial Chamber

In Tutankhamun's burial chamber, an extraordinary painting shows Ay, wearing the Blue Crown of Kingship, officiating at the young man's funeral. By burying the king, he was acting as Horus for his father, Osiris, and establishing a claim to the throne. How had he been able to position himself as heir?

Ay had been the Commander of all the Horses of his Majesty during Akhenaten's reign. Keith C. Seele has suggested this title could be interpreted as "General of the Royal Chariotry," a commander of combat forces. As such, Ay may have been personally familiar with the state of affairs in the Levant. He had also been True Scribe of the King, something like a personal secretary to the ruler. The title Ay used most often, and which became part of his name as king, was It-Netjer (God's Father). Some scholars have suggested on the basis of this title that he was Akhenaten's father-in-law, father of Nefertiti. However, as his only known wife and later queen, Tiy, was “Nurse of the Great King's Wife, Nefertiti,” not mother, he may have been the queen's foster-father. These and other titles show that Ay was a central figure during the Amarna period, though there is little evidence for him at the seat of government during Akhenaten's last eight years. This would make sense if he had been commanding some of the Egyptian forces in Syria during these years, and /or had wanted to distance himself from the more extreme manifestations of the king's religious revolution. Either during these later years of Akhenaten, or during the reign of Tutankhamun, Ay assumed the title of Vizier, and the epithet, "Doer of Right." But Ay's close connections with the Amarna family had tainted him politically. It was not he, but Horemheb, who held the reigns of power during the boy's minority. Did the two men work together? Were they rivals, even enemies? It has been suggested that Horemheb's wife, Mutnodjmet, was Ay's daughter. As King, however, Ay named another man, Nakht-Min, as heir-apparent. General Nakht-min may have been Ay's own son, but predeceased the old king. Four years after Ay's coup, Horemheb finally succeeded to the kingship.

Later generations included Ay in the general obliteration of the Amarna period from Egypt's official history. But Horemheb and Pa-ramess would be remembered as the kings who restored Maat, who brought truth and justice back to Egypt. For hundreds of years prayers were addressed to Horemheb and Ramesses I.