The Once and Future Pharaoh

In September 2003, a most unusual shipment from Atlanta Georgia will arrive in Egypt. A king will be coming home. Three thousand years after his death, and over a hundred since he was taken from his native land to sojourn at Niagara Falls, Ramesses I will be landing at Cairo airport.

Ramesses I was the founder of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, father of Seti I, and grandfather of Ramesses II, often called Ramesses the Great. After ruling only two years, around 1291 BC, Ramesses I died and was buried in his unfinished tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Within four hundred years of the burial, his body had been moved from his sarcophagus to a replacement coffin, and taken for safety (and other reasons), from the royal necropolis. Though the complete itinerary cannot be traced, his mummy certainly rested in temporary locations before priests and officials in the reign of Sheshonk II of the Twenty-Second Dynasty found what they hoped would be an eternal resting place for him. By 890 BC, they had sealed the replacement coffin into a tomb high in the cliffs above Hatshepsut's temple at Deir el Bahri.

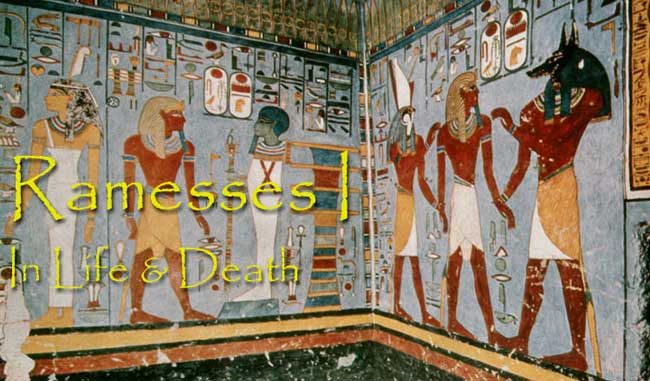

The Solar Barque from KV 16

In 1817, Giovanni Baptista Belzoni opened Ramesses I's original tomb, KV 16. Wooden guardian figures and strange images of underworld deities greeted the explorer, and beautiful paintings from the Book of Gates decorated the walls of the burial chamber, but the king's mummy was not there. His fate was completely unknown until 1881, when Emile Brugsch, acting head of the Antiquities Service, entered the tomb in the cliffs, DB 320. An amazing array of royal mummies, including Seti I and Ramesses II lay in replacement coffins, crowded into a long undecorated corridor, stripped of their gold. Fragments of Ramesses I's replacement coffin were found, but where was his body?

There are many chapters in the story of the life and afterlife of Ramesses I. One is the tale of a family of local guides on the West Bank who had found the cache of royal mummies sometime between 1860 and  1871. After the Abd el Rassul family had explored the tomb, they began selling the contents.

1871. After the Abd el Rassul family had explored the tomb, they began selling the contents.

To avert government intervention, the family were careful to sell only a few artefacts at a time. Their agent was Mustapha Aga Ayat. Mustapha was a wise and hospitable man worthy of his own book. As well as serving as Vice-Consular Agent at Luxor for Britain, Belgium and Russia for over forty years, he and his son dealt in antiquities. Around 1860, they sold a mummy and coffins to a Canadian, James Douglas Jr. Douglas (in the centre right) was buying Egyptian antiquities for his friend Sidney Barnett. Barnett and his father, Thomas, owned and operated a Museum in Niagara Falls. They wanted to add an Egyptian component to their attraction.

When DB 320 was finally located and cleared by Service des Antiquités in 1881, only the damaged replacement coffin containing some loose bandages remained of the burial of Ramesses I. The mummy had probably been moved into a set of more durable, attractive, and saleable coffins. Any identifying documentation which had survived from Ancient times was lost. Neither Mustafa nor Douglas would have had any way of identifying the mummy, nor even of suspecting that he was royal. As of this writing, there is no proof that Ramesses I was the mummy Douglas purchased. The circumstances of the purchase are suggestive, but not conclusive.

For the next hundred and twenty years or so, the royal mummy became part of the story of the Niagara Falls Museum. This privately owned museum was a real cabinet of curiosities, filled with treasures and trifles from a dozen cultures. Along with eight other Ancient Egyptians, mastodon and whale skeletons, two-headed calves and collections of minerals and weapons from all over the world, Ramesses crossed the Niagara River from Canada to New York State, and then back again as the creation of national parks appropriated the Museum's prime locations. The mummies were sometimes displayed inside their coffins and sometimes beside them. During the collection's relocations, some of the bodies and coffins got mixed up. The final stop was a former corset factory on the Canadian side, with a wonderful view of the American Falls. While the mummies were in Niagara Falls, many enthusiasts and scholars looked at the handsome mummy with the Ramessid profile and wondered if he might be one of the missing kings of Egypt. Finally, in 1999, the whole Egyptian collection was purchased by the Michael C. Carlos Museum of Emory University, Atlanta.

|

|

Mummy of Ramesses I in Niagara Falls

Coffin of Ramesses I

One of the most interesting chapters in the tale of Ramesses I concerns the investigation of the mummy from the Niagara Falls Museum by a team at the Michael C. Carlos Museum of Emory University in Atlanta Georgia, led by Dr. Peter Lacovara, Curator of Ancient Art. You can follow Dr. Lacovara and his team as they continue to study the mummy of Ramesses I and the rest of the Niagara Falls Collection at the Michael C. Carlos Museum web site and in the Museum's beautifully illustrated catalogue.

Eventually, the story of Ramesses I will end with his triumphant return to Egypt and the city that he ruled as Waset, modern Luxor. This essay will attempt to fill in some of the earlier parts of the story, and tell of a solider named Pa-ramessu who rose to become Vizier of Egypt and, eventually, King Ramesses I.