Vizier

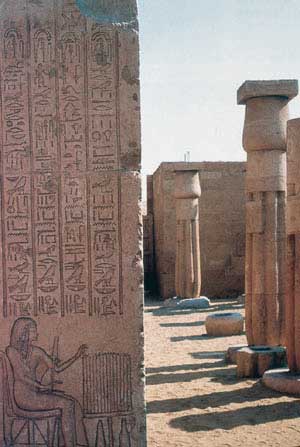

As General of the Army and later as King, Horemheb was Pa-Ramessu's patron and friend. After a long reign, Horemheb would be buried by his trusted comrade in the Valley of the Kings in a large tomb of revolutionary design and exquisite workmanship. While still a general, however, Horemheb had been constructing a large burial place at Saqqara, near the capital city of Memphis. The cemetery there is one  of the most ancient and sacred in Egypt. Horemheb's monument (left) is in sight of Djoser's step pyramid (Saqqara: The Step Pyramid of Djoser), as well as the pyramids of Wenis, Userkaf and Teti. The necropolis of Dashur, with the great pyramids of Sneferu can be seen to the south, as can the smaller pyramids of the Sixth Dynasty. On this most hallowed ground, Horemheb was preparing a tomb commensurate with his standing in the country. Above ground, the tomb takes the form of a temple, with a monumental gateway, paved forecourt, open courtyards, a statue room and offering chapel.

of the most ancient and sacred in Egypt. Horemheb's monument (left) is in sight of Djoser's step pyramid (Saqqara: The Step Pyramid of Djoser), as well as the pyramids of Wenis, Userkaf and Teti. The necropolis of Dashur, with the great pyramids of Sneferu can be seen to the south, as can the smaller pyramids of the Sixth Dynasty. On this most hallowed ground, Horemheb was preparing a tomb commensurate with his standing in the country. Above ground, the tomb takes the form of a temple, with a monumental gateway, paved forecourt, open courtyards, a statue room and offering chapel.

The white limestone walls were beautifully decorated by the finest artists of the day. Though damaged, the reliefs contain a wealth of information about military matters: scenes of army camps, soldiers on campaign, chariots, and prisoners of war. The South Wall of the Second Court may provide the first glimpses of the future Ramesses I. Horemheb is shown seated while army scribe named Ramose stands behind his chair. Ramose is one of the possible spellings for Pa-Ramessu's name. Although 'military scribe' seems a rather lowly title for Pa-Ramessu at this point in his career, the image originally depicted Horemheb's secretary, Sema-tawy. When the name 'Ramose' replaced 'Sema-tawy,' there might not have been enough space to put Pa-ramessu's current titles. It's possible that the entire scene represents an event early in Pa-ramessu's relationship with Horemheb, during the reign of Tutankhamun. This image may even represent some other 'Ramose.' Another image from the tomb may more probably be identified as the face of the future pharaoh.

Horemheb bestowing honours on an unnamed official.

Horemheb's powers under Tutankhamun were unprecedented. The Sakkara tomb not only shows him being rewarded with the gold of honour by a king, but in a scene on a loose block, Horemheb is deputizing for the king, officiating as another man is rewarded for extraordinary services. The name of colleague is unfortunately not preserved, but the portrait on the block is quite extraordinary. The mature man is heavy-set, with the sort of body shape caused by too much desk work. He has a high-bridged, prominent nose; one might say, a Ramessid nose. The excavator, Geoffrey T. Martin, considers it “highly probable”that the unnamed official is Pa-ramessu.

Other evidence from Sakkara suggests that Pa-ramessu began to build a tomb near his colleague. The contemporary tomb of a deputy in the army named Ramose was found by Martin just to the north of Horemheb's complex. It was never finished. The outer court was carefully dismantled, brick by brick within a generation. It would have been natural, if the tomb belonged to Pa-ramessu, for work on it to have stopped when he became king. The appealing theory that it was indeed his is re-enforced, though not proven, by the fact that this prime real estate in the necropolis was taken over by princess Tia, sister of Ramesses II, and grand-daughter of Pa-ramessu.

Even with the deaths of Tutankhamun and Ay, Pa-ramessu would not have been immediately considered in line for the kingship. At his accession, Horemheb was a vigorous man in early middle age. A childless widower after the death of his first wife, Amenia, he had married again and doubtless expected to father sons. But despite many pregnancies, his wife Mutnodjmet had been unable to provide him with an heir and seems to have died, herself middle-aged, in childbirth during his thirteenth year. In contrast, Pa-Ramessu's handsome, intelligent son, Seti was already beginning his career in the military. Perhaps by the time Horemheb realized that he would not be the founder of a dynasty, young Seti had married a soldier's daughter named Tuya, and had begun a family of his own. At some point, Horemheb must have met and been enchanted with a bright, energetic red-haired boy, Pa-ramessu's grandson, the future Ramesses the Great.

career in the military. Perhaps by the time Horemheb realized that he would not be the founder of a dynasty, young Seti had married a soldier's daughter named Tuya, and had begun a family of his own. At some point, Horemheb must have met and been enchanted with a bright, energetic red-haired boy, Pa-ramessu's grandson, the future Ramesses the Great.

Horemheb (right) had no family to succeed him nor to complicate the succession. His Coronation Inscription tells of his youth in Henen-Nesut (now Ihnasiya el-Medina) a town at the mouth of the Fayuum, away from the centres of power. His name honoured the local form of Horus. To buttress his claim to the throne, Horemheb asserted that his royal and divine nature had been obvious to anyone who ever looked upon him, even as a child:

He came forth from the body, clad in majesty; the aspect of a god upon him; . . .Bowed unto him was the arm in youth, the ground kissed [before him] by great and small. Food in abundance attended him while he was (still) a child without understanding. . . . The form of a god was his aspect ….

However, he never named his parents, which would suggest either that he was a truly self-made man, or that naming them would have been a political liability. Had his family been inextricably involved in Akhenaten's regime and policies? There are no traces of Horemheb's career or activity at Amarna, though some scholars have suggested that he served Akhenaten under a different name, not Hor-em-heb (“Horus is in festival”) but Pa-Aten-em-heb (“the Aten is in festival”). He would not have been the only personality of the time to survive the change of regimes by altering the divine element in his name. Otherwise, he seems to appear out of thin air during Tutankhamun's reign, already possessing all the highest titles of military and civil authority, “even outranking the two viziers who traditionally served as prime ministers directly under the pharaoh.” Perhaps he had spent the Amarna years on active duty outside the borders of Egypt, keeping his distance from Akhenaten's revolution, while gaining a high reputation among the native military and foreigners alike. In his Sakkara tomb he boasted that,

his name was famous in the land of the Hittites

During action in Syria he may have met a young Pa-Ramessu, who followed his own father, Seti, as Commander of the border fortress of Sile. A generation older than Pa-ramessu, Horemheb may well have watched the young soldier grow up, and been impressed with his intelligence, integrity, and loyalty.

Horemheb's task as king, and the one he would increasingly share with Pa-ramessu, was immense. The army and the civil administration, including the judiciary, had to be re-organized and reformed. The traditional religion was to be restored, and the economy needed attention, too. Temple construction, with the need for quarrying, building, decoration, and the manufacture of all sorts of cultic vessels and implements, spoke to most of these issues. Construction occupied the rural population during the flood seasons of the Nile, and soldiers, priests and artists all year long. Such activity was the visible sign that Maat was being upheld, truth and justice were being served. At Karnak, Horemheb added the ninth, tenth and second pylons to Amun's temple. During this work, he ordered Akhenaten's structures to be dismantled, accidentally preserving the information on the decorated talatat by using them as fill. As king, Horemheb retained his direct authority over the army, and may have continued to lead campaigns. Pa-Ramessu was appointed Vizier to deal with all internal and civil matters.

Karnak. Sphinx of Horemheb.

The office of Vizier goes back to the time of the pyramids, and often was held by royal sons. Famous wise men, such as Ptahhotep and Amenhotep son of Hapu had been viziers. The job was the perfect preparation for kingship, and had sometimes served as the path by which a man who was not in the direct succession became king. Amenemhet I, for example, had been vizier to the last Montuhotep. Hatshepsut's father, Tuthmosis I, had been general and vizier to Amenhotep I, and Horemheb himself had been general and deputy for Tutankhamun. It is sometimes claimed that Amenemhet, Tuthmosis, Horemheb and Pa-ramessu were commoners. This is not very likely. Even in democracies, it's a very rare boy or girl of humble birth who reaches the highest offices. The population of ancient Egypt at this time was only a few million people. Viziers who became kings were members of the nobility; Tuthmosis I and Horemheb may have had connections by marriage with the royal family. Pa-Ramessu with his Northern military heritage, may have really brought fresh blood and new traditions into the office of vizier and eventually into the kingship.

The office of vizier is one of the best understood in the Ancient Egyptian civil administration. Four copies of a text known as the Duties of the Vizier, were preserved in the tombs of Viziers at Thebes during the New Kingdom. By comparing the legislation enacted during the reign of Horemheb with the list of civil responsibilities in the text, it should be possible to understand to what extent Pa-Ramessu shaped the reorganization of Egypt. The Ramessid Era owes its glory and stability in very large measure to his efforts.

Horemheb's concern for religious matters was clear as early as Tutankhamun's Restoration Stela, for which he claimed responsibly by substituting his name for the young king's. The empty sanctuaries were dealt with first. New statues of the gods, tabernacles for them to live in, and barques for their travel were fashioned of the most costly materials: electrum, lapis-lazuli, turquoise and fine woods. In contrast to Akhenaten, who had preferred 'new men' who would owe their careers only to the king, the Restoration Stela commands that the ranks of the clergy be filled with “the children of the chiefs of their towns, as the son of a wise man, whose name is known.” Because temples required more than statues and priests he “consecrated male and female servants, the musicians and dancers who had been maidservants in the palace. Their wages are charged to the palace and the treasury of the Lord of the Two Lands.”

Karnak: A procession of priests

Horemheb's Coronation Inscription claims that the restoration of the temples was still incomplete when he became King. The text speaks of looking throughout the country “for the precincts of the gods which were as mounds of sand." Pa-Ramessu was appointed imy-r hm ntr n nb ntrw, "Overseer of the Priests of All the Gods," to finish the job. After the temples were swept clear of the blown sand which had filled them, priests were needed to carry on the divine offices. Tutankhamun's Restoration Decree had authorized new priest of two classes, the lowest class of w3b, 'pure' priests and hm ntr, the 'prophets.' Each temple also needed iterate men to read the prayers and assure that rituals were performed properly. These 'lector priests' were chosen from among the army scribes. Men of known military families were placed into new positions, and given stipends to prevent bribery. What had become of the old priestly families? Some had survived, but it was Pa-Ramessu who chose the men who would replenish their ranks, not the priests who had either joined Akhenaten's heresy, or been unable or unwilling to defend the temples against him. It was Pa-Ramessu who would reward or punish the new clergy for the performance of their duties. As vizier, Paramessu was:

[It is] he who investigates concerning the ending of any divine offering. It is he who provides every provision consisting of food to everyone to whom it should be given.

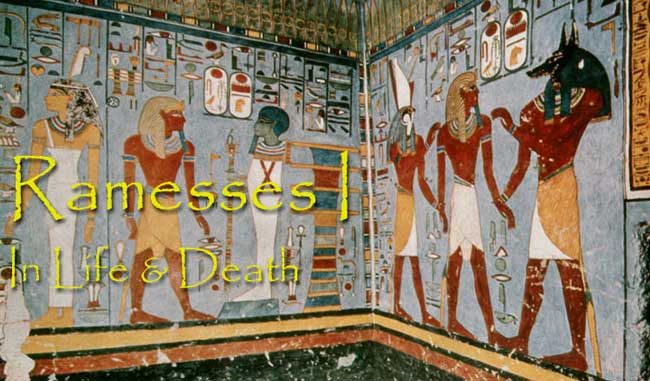

During his years in office, Pa-Ramessu must have met with every member of every priesthood throughout Egypt. While maintaining his family's devotion to Seth, he would have learned the natures and rituals of all the gods. He passed this interest and knowledge on to his son Seti, and grandson Ramesses. Theology flourished under his patronage. The first copies of a new Book of the Underworld, the Book of Gates, would appear during this period, and decorate the walls of Horemheb's tomb and his own in the Valley of the Kings. New hymns and prayers began to be composed in answer to the religious issues raised by Akhenaten. A renaissance of religious thought began.

Without justice, there is no peace and no prosperity. According to his Edict, Horemheb “took up the scribe's palette and the papyrus roll, and he put into writing,” enactments to promote justice. In every instance, the Vizier actually implemented and oversaw the legislation.

The Edict called for the appointment of new judges:

[men who were] discreet, whose characters were good, and who knew how to seek out people's thoughts, obedient to the words of the king's house and to the laws of the council chamber. . . . I placed instructions in front of them and laws as [their] regular concern.

Pa-ramessu's responsibilities, as outlined in the Duties of the Vizier, show how he was responsible for enforcement of the Edict's provisions:

It is he who appoints the leading members of the magistracy [in] Upper and Lower Egypt, in the Thinite Nome, in the Head of the South. It is to him that they report the matters accomplished under their charge, at the beginning of every four months. it is to him that they bring the pertinent documents in their charge, together with their councils. [R22]

It is he who appoints the overseer of police in the halls of the palace. It is he who holds the hearing of the mayors and settlement leaders who have gone out in his name to Upper and Lower Egypt. [R26]

It is to him that every legal matter has to be reported. It is to him that the affairs of the fortress of Upper Egypt have to be reported, as well as every arrest of any who is involved in plundering. . . . It is he who assigns the spoils to each town district. It is he who judges him (the plunderer). [R26]

And finally,

It is he who hears every case. [R29]

In theory at least, Pa-Ramessu's authority extended from the most serious malfeasance to petty crime. In practise, he must have delegated some of his authority. He commanded a small army of scribes and bureaucrats, but in the end, the responsibility to ensure the honesty and competence of civil servants was his.

The mayors, the settlement-leaders and every common citizen report to him their deliveries. Every overseer of the district and every policeman reports to him every conflict. [R32]

Apart from the major areas of civil law and religion, the Vizier had responsibility for the economic health of the country, from making an inventory of all the cattle, to inspecting

the drink supply at the beginning of every ten days.[R31]

What we might call 'forestry' was under his control as well, and irrigation:

It is he who dispatches to cut down sycamores according to what has been said in the palace. It is he who dispatches the councillors of the district to construct the 9inlet-/outlet-) channels in the whole country. it is he who dispatches the major and the settlement-leaders to take care of the cultivation and the harvest.

And though Horemheb kept control of the military, particularly in the areas of war and peace, Pa-Ramessu was not entirely cut off from his old sphere and old comrades. He still had contact with them, and responsibility for the deployment of soldiers within the country.

It is he who assembles the army contingent that escorts the Lord when sailing downstream and upstream. it is he who organizes the remainder (of the army) that stays behind in the Southern City and in the Residence according to what has been said in the palace. it is to him, to his office, that the captain of the Ruler's crew and the army staff have to be brought in order that they be given the instruction of the army. [R23]

Could there be any better training for a king? When Pa-Ramessu finally became Ramesses I, he passed the office to vizier to his son Seti.

The length of Horemheb's reign is difficult to determine, as he claimed and was credited in later histories with all the years since the death of Amenhotep III. Certainly, it was a long reign, perhaps as long as twenty-eight years during which peace, order, and good government returned to Egypt. His final service to his country was the choice of co-regent and successor. By deciding to share his throne as well as his burdens with Pa-Ramessu, Horemheb ensured that Egypt would have the finest of kings, and a powerful and intelligent new dynasty.