This relatively small site lies on the outskirts of Mgarr village, about a kilometre away from Skorba. Excavation of the site, whose name means ‘of the large stones’ began in 1923 under the direction of Sir Themistocles Zammit and continued for two additional seasons, in 1925 and 1926.

As was so often the case, there was a pair of temples. The larger of the two is typically trefoil with a concave façade opening onto a spacious forecourt. It dates to the Ggantija Phase (c.3600-3200 BC). The smaller one was added some time later, perhaps during the Saflieni Phase (c.3200-3000 BC). It was grafted onto the side of the earlier temple and is a modified version of the trefoil plan. The temples were not the earliest buildings on the site but replaced an earlier village characterized by Mgarr pottery.

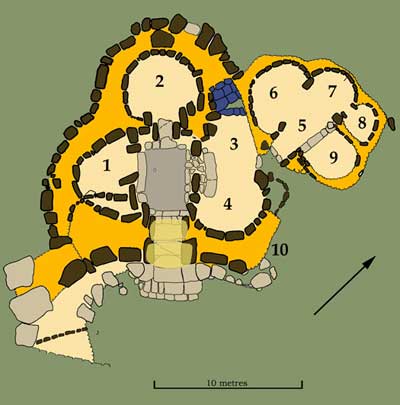

The site comprises two adjoining buildings, a main building, dating to the Ggantija Phase, that probably began as a three-apse temple laid out around a central court, and a smaller one that was added on later, probably late in the same phase or early in the Saflieni. It has a typical concave façade and a spacious forecourt that slopes away from the building. There were benches running along the façade to either side of the entrance—possibly for the placement of offerings and votives.

typical concave façade and a spacious forecourt that slopes away from the building. There were benches running along the façade to either side of the entrance—possibly for the placement of offerings and votives.

Three broad stone steps lead up to the monumental entrance to the main temple. Originally, it was made up of two pairs of stone uprights supporting massive lintels. These rested on a single large stone slab that runs nearly the entire length of the passage. However, the trilithons were badly damaged in the 1880’s in order to make room for the branches of a carob tree. The landholder removed the lintels and cut down the outer pair of uprights to mere stumps. One of the lintels was placed on top of the stumps while the other was dragged a short distance away. It was reconstructed by Charles Zammit in the 1930’s.

The stone paved entrance passage leads to a rectangular courtyard that is several centimetres lower than the rest of the building and is surrounded by a kerb of small stones. Each apse is entered through a pair of megaliths but the nearly circular Apse 2, which is on the main axis, is  clearly the most important room in the temple although it lacks an altar. In fact, none of the apses show much in the way of decoration or furniture. The walls were made out of boulders that were barely shaped if at all.

clearly the most important room in the temple although it lacks an altar. In fact, none of the apses show much in the way of decoration or furniture. The walls were made out of boulders that were barely shaped if at all.

Apse 4 was subsequently enlarged and remodelled to provide a link (5) to the Small Temple (left), which is essentially a smaller version of the main one. Instead of a connecting passage, however, there was a an extra apse (8) on the right-hand side. The flight of steps (shown in blue on the plan) in the angle between the two buildings is a modern restoration by Zammit.

Undoubtedly, the most significant artefact to come out of the site is a limestone model of what looks like a temple (opposite right). It is a tiny object, only some 3 cm. high and less than 5 cm. in diameter. It has a monumental trilithon entrance and walls made up of alternating broad and narrow stone slabs. The roof appears to be made out of long stone slabs, which is interesting because actual slabs such as these have never been found in an archaeological context.