The Giparu

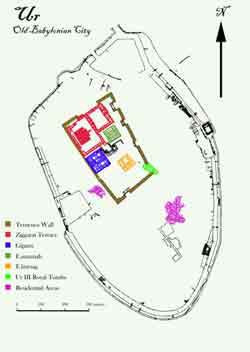

The temple of the goddess Ningal (right), wife of Nanna, lay in the area immediately southwest of the Ziggurat Terrace and was separated from it by a paved street. During his excavations Woolley found no less than thirteen door sockets bearing inscriptions of Ur-Nammu suggesting that the original foundation was his. They were all found in secondary locations, however, and the earliest physical remains are associated with his grandson, Amar-Sin. The walls were predominantly of sun-dried brick and were overthrown in the Elamite sack of the city. It lay in ruins for half a century before it was rebuilt during the reign of Gungunum, king of Larsa and overlord of Ur. However, the person directly responsible was the high priestess of Nanna, Enanatuma. She had been appointed priestess by her father, Ishme-Dagan of Isin, according to an old tradition whereby the king’s daughter filled that role. When her father was supplanted by Gungunum, she somehow managed to hold onto her position Her stamped bricks and dedications are found throughout the building. This time the walls were constructed of baked brick with a core of rubble or, in the case of the large external walls, mud brick. The corridors and the rooms that saw a lot of traffic were paved with baked brick, otherwise packed earth was considered sufficient. Apart from some minor changes in the southern corner, the restoration follows exactly the same layout as its  predecessor. However, this temple was destroyed by the Babylonian king, Hammurabi’s son Samsu-iluna, sometime during the last half of the 18th century BC and, in many areas, only the foundations have survived.

predecessor. However, this temple was destroyed by the Babylonian king, Hammurabi’s son Samsu-iluna, sometime during the last half of the 18th century BC and, in many areas, only the foundations have survived.

The building is nearly square, measuring 79 x 76.5 metres, and was surrounded by substantial brick walls over 4.5 metres thick. These were buttressed on three sides but apparently not on the southeast side. A narrow passageway (left) ran just inside the outer wall, around three of its sides, while another, running the width of the building divides it into two main blocks. Each block is quite distinct and has its own formal entrance. Even so, there are a number of doorways from each that connect to the central passage, making it relatively easy to get from one to the other. There are sanctuaries in both halves—to Ningal in the south-eastern wing and to an unknown deity in the north-western. Woolley believes there were staircases in the perimeter corridor leading to the roof, an important feature of most Mesopotamian temples, however he was unable to find any physical evidence to confirm this.

The Northwest Wing

The Northwest Wing was subdivided into three distinct units. The largest of these is a T-shaped arrangement of rooms, which include a major sanctuary together with its courtyards and service rooms. In each of the angles was a smaller suite of rooms, isolated to some degree from the rest of the building. The eastern corner has been badly disturbed is it is impossible to determine the function of any of the rooms but the southern corner contained mainly cult rooms. The main entrance is set off centre in the north-western façade, which has a rather curious appearance. It is not uniform in thickness but increases by a series of offsets from 4.7 to 6.6 metres. To one side of the doorway is a set of three tanks made out of baked bricks and lined with bitumen. Presumably, these were used for lustrations before entering the temple.

The entrance itself, as restored by Woolley, was a double doorway (A1) that led indirectly to the sanctuary. The nest room (A2) was an antechamber with doorways leading to the perimeter corridor and the roof.  The only doorway that Woolley found led to one of the antechambers of the temple (A4) but he felt there may have been another, on the opposite side, leading to the outer courtyard (A6). This forecourt was badly disturbed, as were the rooms surrounding it. Along with the adjacent suite of rooms in the eastern angle, they may have been part of a residence for the high priestess. On the south-western side of the courtyard, room A5 contained a platform set in a broad niche (right) that was aligned directly with a rather formal looking doorway and almost certainly contained a statue. Doors at either end of the room led to the main courtyard of the sanctuary (A16) by way of a long antechamber (A4) that seems to have been used for lustration. The room was lined with brick benches, waterproofed with bitumen. The floor was simlarly water-proofed and sloped away to a terracotta drain.

The only doorway that Woolley found led to one of the antechambers of the temple (A4) but he felt there may have been another, on the opposite side, leading to the outer courtyard (A6). This forecourt was badly disturbed, as were the rooms surrounding it. Along with the adjacent suite of rooms in the eastern angle, they may have been part of a residence for the high priestess. On the south-western side of the courtyard, room A5 contained a platform set in a broad niche (right) that was aligned directly with a rather formal looking doorway and almost certainly contained a statue. Doors at either end of the room led to the main courtyard of the sanctuary (A16) by way of a long antechamber (A4) that seems to have been used for lustration. The room was lined with brick benches, waterproofed with bitumen. The floor was simlarly water-proofed and sloped away to a terracotta drain.

The main courtyard is fairly typical of a Mesopotamian temple of the period. It was essentially a gathering place for the select  few—the high priestess along with her attendant priests and priestesses and (on occasion) the king—who offered sacrifices on behalf of the people as a whole. In one corner was a small compartment (A17) which contained a number of contemporary clay tablets. Not much is known for certain about the rest of the rooms surrounding the courtyard, apart from those on the southwest side. There, a pair of massive doorways (one of which is shown in the photograph, left) framed by an elaborate arrangement of niches and buttresses gave access to a pair of small antechambers (A27 & A28). These in turn led to the cella (A30), the principal cult room of the temple.

few—the high priestess along with her attendant priests and priestesses and (on occasion) the king—who offered sacrifices on behalf of the people as a whole. In one corner was a small compartment (A17) which contained a number of contemporary clay tablets. Not much is known for certain about the rest of the rooms surrounding the courtyard, apart from those on the southwest side. There, a pair of massive doorways (one of which is shown in the photograph, left) framed by an elaborate arrangement of niches and buttresses gave access to a pair of small antechambers (A27 & A28). These in turn led to the cella (A30), the principal cult room of the temple.

Essentially, a Mesopotamian cella consisted of an altar in the middle of the room and a niche in the wall behind it for the cult object. Normally there was a podium or platform upon which stood the statue of the deity. In this particular case, the altar is located along the long rear wall of the cella. On either side of it are pedestals for votives, thanks offerings to the deity for blessings received or anticipated. Most often these took the form of a figurine of the worshipper in some pious pose.

Altar and pedestals in Room A30

The niche was expanded into what amounts to a separate room (A31) located at the northwest end of the main chamber. Unfortunately, the room was badly disturbed and no trace of the cult statue nor the podium has survived. In fact, even the name of the deity is unknown. A temple was essentially the abode of the deity and contained many of the features of a domestic house. There were storerooms for the possessions of the god, things like jewellery and fine clothing, etc. Room A29 was probably the treasury while A26 may have been used to store oil—a large jar had been buried into the floor up to the neck.

The south corner contained an unusual suite of rooms. Rooms B1-B4 formed a small shrine, a scaled- down version of its neighbour— except that this one contained two cellae. Next to it was a set of three rooms (B6-8) enclosed by a corridor (B5). The central room (B7) contained a standing stela and another, smaller pair lying face down on the floor (left). They were inscribed with a dedication to the goddess by Amar-Sin, suggesting the suite may have been a shrine to the deified king.

down version of its neighbour— except that this one contained two cellae. Next to it was a set of three rooms (B6-8) enclosed by a corridor (B5). The central room (B7) contained a standing stela and another, smaller pair lying face down on the floor (left). They were inscribed with a dedication to the goddess by Amar-Sin, suggesting the suite may have been a shrine to the deified king.

The suite in the east corner was very badly preserved and only the foundations of the Neo-Sumerian period have survived. The walls and floors were gone so it is impossible to say what its function was. At some point a number of subterranean brick tombs were constructed, one in each of the rooms. All of the tombs were plundered long ago but it is possible that they belonged to the various high priestesses of the temple.

The Ningal Temple

Plan of the Ningal Temple in the Giparu

The Southeast Wing is completely taken up by a temple to Ningal (right), the wife of the city god. The entrance to the temple was monumental, with massive towers on either side of the doorway and a fairly long entrance passage. Typical of Mesopotamian temples (and unlike Egyptian or Greek temples) the approach to the sanctuary was indirect. Visitors first had to pass through a pair of lobbies and the doorways of the second one were offset, so that it was impossible to see directly into the temple from the street. The lobbies led to a small forecourt (C3) where the axis of approach to the sanctuary turns 90 degrees. Little of the court has survived but enough remains to confirm the presence of some small rooms at its north-western end.

The Southeast Wing is completely taken up by a temple to Ningal (right), the wife of the city god. The entrance to the temple was monumental, with massive towers on either side of the doorway and a fairly long entrance passage. Typical of Mesopotamian temples (and unlike Egyptian or Greek temples) the approach to the sanctuary was indirect. Visitors first had to pass through a pair of lobbies and the doorways of the second one were offset, so that it was impossible to see directly into the temple from the street. The lobbies led to a small forecourt (C3) where the axis of approach to the sanctuary turns 90 degrees. Little of the court has survived but enough remains to confirm the presence of some small rooms at its north-western end.

The main courtyard of the temple (C7) was well-provided with cult installations. In the northern corner was a brick water tank lined with bitumen and, next to it, a limestone pillar standing some 80 cm above the floor. The tank was undoubtedly used for lustration and Woolley suggests that a vessel of holy water was placed on the pillar.

View from C3, looking through the Courtyard (C7) to the inner sanctum (C27)

Directly in front of the entrance from C3 was a platform 2.2 metres square and 90 cm high. There was a fairly large (1 x 0.9 metres) slot in the top that was designed to hold a diorite stela of Hammurabi—a number of fragments of it were found in and around the socket. Next to it was a much lower platform with a pair of rectangular compartments in the top. No trace of bitumen was found, so presumably they were not designed to hold water but little more can be said about them. On the far side of the courtyard, directly in front of the entrance to the shrine, was a brick altar measuring 1.55 x 0.95 metres and standing 1.05 metres high. In front of the altar was a rectangular gap in the paving where Woolley believes an altar of table made out of some perishable material such as wood once stood. Against the wall, on either side of the doorway were a number of low platforms where votives (usually in the form of statues or stelae of royal benefactors) were placed. Fragments of a calcite stela naming Rim-Sin of Larsa were found in front of one of them.

Reconstruction of the Ningal Temple

The doorway to the sanctuary proper was framed by reveals and was probably arched. It led through a pair of wide antechambers (C19-C22) which appear to have been shrines for lesser deities—a statue of the goddess Bau was found in C20, next to a low brick pedestal. The inner sanctum (C27) was entirely occupied by a brick pedestal for Ningal’s statue and a low podium for the priestess to stand. The whole suite was on a long axis with the inner sanctum directly visible from the courtyard (when the doors were open).

Inner Sanctum of the Ningal Temple

Since the temple was considered to be the abode of the goddess, it was provided with all of the standard amenities of a domestic house. Her bedchamber was probably in C28 while C23 has been identified as her treasury. Fragments of stone vessels dedicated by a number of different rulers were found on the floor of the latter. On either side of the central unit were storerooms and workshops—C10 contained a weaver’s pit, an oval hollow where the weaver sat to operate a hand loom.

Weaver's Pit in Room C10

Behind the shrines were other service rooms, including a large kitchen suite (C32-34). The main work area (C32) was a small open courtyard with two smaller, covered rooms at one end.

Plan of the Kitchen Area in the Giparu

The court contained a well and a water tank along with a copper ring fixed in the ground in front of the well (presumably to fasten the bucket). Up against the southeast wall were two fireplaces for boiling water. A counter, heavily scored with knife marks, was located against the short wall between the doorways to the other two rooms. Of the smaller rooms, one contained a domed bread oven (C34) while a cooking range was found in the other (C33). The rest of the rooms around the kitchen (C29-31; C35-41) were used for storage. In C29 Woolley found a number of large storage jars lined up against one of the walls.

The court contained a well and a water tank along with a copper ring fixed in the ground in front of the well (presumably to fasten the bucket). Up against the southeast wall were two fireplaces for boiling water. A counter, heavily scored with knife marks, was located against the short wall between the doorways to the other two rooms. Of the smaller rooms, one contained a domed bread oven (C34) while a cooking range was found in the other (C33). The rest of the rooms around the kitchen (C29-31; C35-41) were used for storage. In C29 Woolley found a number of large storage jars lined up against one of the walls.