Construction

The primary building material was mud-brick, of which the country had an inexhaustible supply. Clay tempered with straw was packed into moulds and simply allowed to dry in the sun. Nothing could be easier or cheaper. Certainly nothing else was available locally. It is very prone to damage  by running water, however, and flooding has always been a problem in Mesopotamia. The builders minimized the effects of this by using kiln-fired bricks for the foundations and lower course of the walls. Thicker, support walls had a core of rubble into which the brickwork was bonded.

by running water, however, and flooding has always been a problem in Mesopotamia. The builders minimized the effects of this by using kiln-fired bricks for the foundations and lower course of the walls. Thicker, support walls had a core of rubble into which the brickwork was bonded.

Interior walls were normally covered with a thick mud plaster and might be whitewashed to help reflect the heat. Some doorways, at least, were arched— a fallen example, made of baked bricks, was found No. 3 New Street (left). Open areas were paved with fired bricks as were some of the larger rooms. Otherwise, packed earth was sufficient for the floors. Roofs were of mud over layers of matting laid on a framework of wooden rafters. They were fitted with projecting gutters. Since drains were often found in the centre of the courtyard, it is assumed that the roofs sloped inwards. Wood was also used for stairways as well as door and window-frames. The doors themselves were also made of wood and swung on doorposts set in sockets of brick or stone.

Private Houses

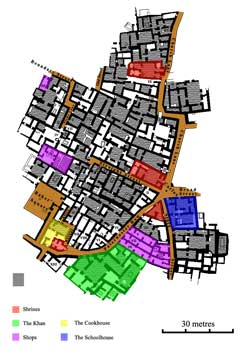

Private houses are all of a broadly similar type although the scale and the exact layout might vary. Typical is the house at No. 3 Gay Street (Woolley named the streets after those he knew well from his student days at Oxford) shown in the plan below. Essentially it consists of a central court with living rooms arranged around it, reflecting both the climate and the need for privacy in a crowded urban environment. The outer walls were thick and solid—excellent insulation against the intense summer heat. If there were any windows looking out onto the street, they were in the upper storeys and presumably shuttered or fitted with latticework screens.. Otherwise, all of the natural light and ventilation came from the courtyard.

A relatively narrow door led straight from the street to a paved lobby, such as the one at 11 Paternoster Row shown right, that was often provided with a drain in one corner. There was undoubtedly a stand with a pitcher of water so that you could wash the dust off your feet before entering the house proper. From the lobby another door led to the central court. It was normally set so that passers by could not see directly into the house and the dust from the street could not blow in. The southwest wind was particularly ill—it was closely associated with the plague and clay masks of the demon-god Pazuzu were often hung on the door jambs to guard against it.

A relatively narrow door led straight from the street to a paved lobby, such as the one at 11 Paternoster Row shown right, that was often provided with a drain in one corner. There was undoubtedly a stand with a pitcher of water so that you could wash the dust off your feet before entering the house proper. From the lobby another door led to the central court. It was normally set so that passers by could not see directly into the house and the dust from the street could not blow in. The southwest wind was particularly ill—it was closely associated with the plague and clay masks of the demon-god Pazuzu were often hung on the door jambs to guard against it.

Plan of No. 3 Gay Street

The courtyard linked all of the elements of the house and saw a lot of traffic moving to and from the various rooms. It was also a major activity area, especially during the heat of the summer. Pack animals and other livestock were often present. For these reasons, the  surface was invariably paved with baked clay tiles, which made it easier to maintain and keep clean. In addition, it sloped towards the centre where there was what the Romans would call an impluvium (a rectangular basin) and a drain to carry away the excess rainwater (it can happen, even in southern Iraq). Left are the well preserved remains of the court at No. 2 Quiet Street.

surface was invariably paved with baked clay tiles, which made it easier to maintain and keep clean. In addition, it sloped towards the centre where there was what the Romans would call an impluvium (a rectangular basin) and a drain to carry away the excess rainwater (it can happen, even in southern Iraq). Left are the well preserved remains of the court at No. 2 Quiet Street.

Around the court were various domestic rooms and a stairway leading to the roof or, in many cases, a second storey. Roof space was (and still is) much used in southern Iraq. Whole families will sleep up there during the summer. One of the rooms, usually at the rear of the house, was a reception room, the equivalent of the liwan found in more recent Middle Eastern homes, where visitors would be entertained and accommodated. On the other side were the stairs and a lavatory, the latter distinguished by its paved floor and drain.  Another ground floor room would be the kitchen, usually equipped with a beehive shaped bread oven and cooking range. There might also be a spare bedroom (with a low brick platform or wooden frame covered with mats) and possibly a workroom. Larger houses might have a second courtyard suite and private lavatory facilities next to the liwan for the use of guests. The photograph (right) shows one of Woolley's excavators sweeping the courtyard while two others are seated in the guest room.

Another ground floor room would be the kitchen, usually equipped with a beehive shaped bread oven and cooking range. There might also be a spare bedroom (with a low brick platform or wooden frame covered with mats) and possibly a workroom. Larger houses might have a second courtyard suite and private lavatory facilities next to the liwan for the use of guests. The photograph (right) shows one of Woolley's excavators sweeping the courtyard while two others are seated in the guest room.

It is assumed that the family lived on a second storey— the walls are certainly thick enough if it followed the same plan as the ground floor—the ceilings would have been too flimsy to support the weight of cross-walls. Postholes in the court of 3 Gay Street suggest that a wooden gallery ran around the interior of the court for communication. The fact that at least one central drain had a curb around it suggests runoff from the roof of such a structure flowed directly into it. No. 11 Paternoster Row had walls thick enough to support a third storey. The odd house has yards at the back with what seem to be storage sheds or stables.

The Private Chapel at No. 1 Boundary Street

Domestic chapels are found at the rear of all of the larger houses and were generally accessed through a door in the liwan. Typically, the chapel consisted of a long brick-paved room, the largest in the house, with an altar at one end. That was certainly the case at No. 1 Boundary Street, the plan of which is shown here (left). The room was paved, which made it easier to keep ritually clean. Woolley suggests that it was very possibly unroofed apart from an awning over the altar, a low brick bench or platform that took up most of one end of the chapel. Votives and other offerings were placed there for the deity, to whom they looked too for protection against the demons that plagued and tormented them. Cut into the wall behind it was a recessed incense hearth with an open chimney running up to the roof. At one end of the altar stood a brick pedestal about 1 metre high. It was covered with plaster which had been into a pattern, usually representing the facade of a temple building, and undoubtedly held the image of the deity. A small chamber associated with the chapel contained the family archives.

Domestic chapels are found at the rear of all of the larger houses and were generally accessed through a door in the liwan. Typically, the chapel consisted of a long brick-paved room, the largest in the house, with an altar at one end. That was certainly the case at No. 1 Boundary Street, the plan of which is shown here (left). The room was paved, which made it easier to keep ritually clean. Woolley suggests that it was very possibly unroofed apart from an awning over the altar, a low brick bench or platform that took up most of one end of the chapel. Votives and other offerings were placed there for the deity, to whom they looked too for protection against the demons that plagued and tormented them. Cut into the wall behind it was a recessed incense hearth with an open chimney running up to the roof. At one end of the altar stood a brick pedestal about 1 metre high. It was covered with plaster which had been into a pattern, usually representing the facade of a temple building, and undoubtedly held the image of the deity. A small chamber associated with the chapel contained the family archives.

Altar in No. 4 Paternoster Row

No trace of wooden furniture has been found but folding chairs and tables are depicted on seals. Wooden or wicker chests for storage are known elsewhere. The floors of the more important rooms would have been covered with rugs and cushions, much as in a traditional Iraqi house. Raised wooden beds and cots are also depicted in terracotta models (such as the one at right). Light could be supplied by small terracotta lamps with wicks floating in oil.

No trace of wooden furniture has been found but folding chairs and tables are depicted on seals. Wooden or wicker chests for storage are known elsewhere. The floors of the more important rooms would have been covered with rugs and cushions, much as in a traditional Iraqi house. Raised wooden beds and cots are also depicted in terracotta models (such as the one at right). Light could be supplied by small terracotta lamps with wicks floating in oil.

The tendency in this period is to bury the dead within the house (in contrast to the earlier practice of interment in large cemeteries). Corbel-vaulted brick tombs for the interment of adults were located beneath the floor, usually at the roofless end of the chapel. When the chamber was full, clay coffins were used for adults and children. Infants were generally interred in clay pots. Grave goods were few, perhaps a cylinder seal or some cheap jewellery together with a pot or two. The close association with the chapel suggests that a cult of the ancestors existed. If so, but the bones of earlier burials were swept aside to make way for the latest interments.

Chapel and tomb at No. 4 Gay Street