Only a dozen examples of this type of tomb have been identified in Orkney— principally on the basis of their size and contents. It belongs to a type of tomb known as a ‘passage grave’ which reached its apogee in the Boyne Valley of Ireland. Certainly at Maes Howe, the type-site, the cruciform layout of the interior  and the orientation of the entrance passage to the sunset on the winter solstice is very much in keeping with what was taking place across the Irish Sea. The tombs at Newgrange in Ireland and Maes Howe share the fact that their entrance passages are oriented towards the sun at the mid-winter solstice. At Newgrange (left) it looks towards the sunrise; at Maes Howe it is the sunset.

and the orientation of the entrance passage to the sunset on the winter solstice is very much in keeping with what was taking place across the Irish Sea. The tombs at Newgrange in Ireland and Maes Howe share the fact that their entrance passages are oriented towards the sun at the mid-winter solstice. At Newgrange (left) it looks towards the sunrise; at Maes Howe it is the sunset.

The pottery found in the Orcadian tombs (where it has survived) is known as Grooved Ware and is decorated with very similar patterns to those found on the walls and kerbstones of the Irish tombs and supports the idea of a direct connection.

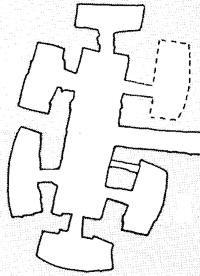

Of the dozen tombs explored so far, seven have been excavated to some extent. In most of them, the internal chamber has a high ceiling and is rectangular in plan but one of them is polygonal. A number of cells, built within the body of the cairn, are connected to the central chamber by small rectangular apertures. The superstructures are normally round or oblong mounds, which can be quite large— Maes Howe is some 35 metres in diameter while Quoyness on Sanday is about half that size. Many of them have been disturbed by subsequent agricultural activity or have been quarried as a source of stone.

There is considerable variation in the length of the burial chamber but normally the width is between 1.4 and 1.8 metres. The longest is Holm of Papa Westray South (ORK 22), which is 20.4 metres long and has no fewer than 14 cells. The walls were made out of larger slabs and blocks than the Orkney-Cromarty  cairns. Some of those lining the lower parts of the walls can be quite massive. This is because they have to support heavy lintels over the entries to the cells and the passageway. Above that level, the slabs are long and thin and are laid in slightly overlapping courses (a technique known as corbelling) in order to reduce the roof span to somewhere between 0.5 and 0.9 metres. A good example can be seen at Cuween Hill (left).

cairns. Some of those lining the lower parts of the walls can be quite massive. This is because they have to support heavy lintels over the entries to the cells and the passageway. Above that level, the slabs are long and thin and are laid in slightly overlapping courses (a technique known as corbelling) in order to reduce the roof span to somewhere between 0.5 and 0.9 metres. A good example can be seen at Cuween Hill (left).

The roof was undoubtedly composed of stone lintels laid crossways—at least that is the case with the two instances where at least some of the material survives— Quanterness (ORK 43) and Wideford Hill (ORK 54). The height of the chamber could be anywhere from 2.4 to over 4 metres.

Overall, the level of craftsmanship is exceptional. The end and side walls are bonded into each other and, in some tombs, a good deal of care went into making the corbelling appear as smooth as possible. The interior layout of some tombs were clearly planned on principles of symmetry with a balanced arrangement of chambers.

The cell entries tend to be small (from 0.6 to 0.73 metres high and from 0.4 to 0.7 metres across). Some of them are hatches in the walls while others are (very) low doors. The cells themselves are irregular in shape—with the exception of Quanterness, where they are rectangular. They range in size from about 1.2 by 0.8 metres to about 3.4 by 1 metre at the base and can be anything from 1.7 to 2.2 metres high.

The layout was designed to be compact, so that they fit within the roughly circular cairn core of the superstructure. The latter consisted of one or more casings of loose stone, each held in place by a revetment wall. Today, there is a considerable amount of stone beyond the limits of  the wall—but does it represent the original limits of the cairn or tumble from the superstructure? Davidson and Henshall believe the latter and hold the view that the outer revetment was also the outer wall of each cairn and that it stood almost as tall as the height of the chamber. On the other hand, Colin Renfrew who excavated at Quanterness believes the revetment was originally buried under the slope of the cairn.

the wall—but does it represent the original limits of the cairn or tumble from the superstructure? Davidson and Henshall believe the latter and hold the view that the outer revetment was also the outer wall of each cairn and that it stood almost as tall as the height of the chamber. On the other hand, Colin Renfrew who excavated at Quanterness believes the revetment was originally buried under the slope of the cairn.

The entrance passages, such as the one at Quoyness on Sanday (right), can be ten metres long or more, and ran at right angles to the main axis of the chamber. They were low and narrow, so that you had to stoop or crawl into the tomb— an appropriate posture when crossing into a higher spiritual plane. The stone blocks used for the walls were often quite large, as were the lintels used for the roof, and the outer part of the passage was often paved. Since they had to be reused repeatedly over the years, it was necessary to be able to close and reopen the tomb. There is evidence that some of them were walled across while at Maes Howe an enormous stone plug was used.